Achieving value for money in PPPs

Value for money is a key driver in public private partnerships. Value for money does not simply equate to selecting the cheapest bid; it means opting for the best solution for the long-term and entering into partnerships that will deliver services which meet citizens' needs.

In the UK, one of the main drivers for PPPs post-1997 was the need to ensure that money spent in a major infra-structure investment programme has been invested wisely. This requires effective procurement tools and good contract management so that projects are delivered on time and within budget, and proper risk transfer.

Traditional procurement meant that if the project went wrong, taxpayers would unknowingly pick up the bill. The use of private capital has increased the transparency of public finances, as the flow of money between partners has to be recorded and accounted for.18

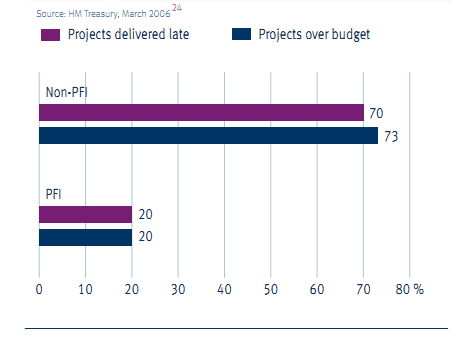

The success of the PFI model in the UK has resulted in the delivery of hundreds of capital projects on time and to budget. This model was developed to counter traditional procurement processes, which often resulted in cost and time overruns and where public facilities were often poorly maintained over their lifetime due to a lack of steady public investment.

UK Treasury figures show that 70% of non-PFI projects were delivered late compared to 20% of PFI projects, and that 73% of non-PFI contracts ran over budget compared to 20% of PFI projects (Exhibit 4).19 A report by the National Audit Office, PFI: Construction Performance, found that 75% of the construction elements of PFI contracts were on time and within budget.20 The PFI model also allows governments the option to spread the cost of the asset over a longer period of time. One of the benefits of using a PFI arrangement is that payment for an asset does not begin until it has been completed and meets the specification. Because providers assume most or all of the construction risk and the finance it gives them the incentive to deliver on time in order to recoup their investment sooner.

|

NATIONAL CASE STUDY 3 |

JAPAN |

|

The election of Prime Minister Koizumi in 2001 saw a move towards PPPs and more private involvement in public services. Prior to 2001, state law in Japan did not allow the government to enter into contracts of longer than five years. To address this, laws enabling the promotion of the PFI were passed to provide a solid legal framework, followed by further legislation to open up the public service provision to private sector involvement. As a result, 94 projects have been launched since the introduction of this legislation, of which 30 have reached contract award stage. Japan's progress in PPP development since 2001 has been much quicker than the UK's over a comparable period. For example, Japan's approach to contracts - traditionally based on trust between the parties rather than explicit contracts - has meant that transactions have been completed in approximately one year, quicker than has been the case in the UK. 21 The breadth of PPP development is also impressive - current projects cover sectors such as government facilities, healthcare, waste disposal, leisure, education and serviced accommodation for public sector workers, and Japan has a further 20 projects in the pipeline. PFI-style contracts in particular are emerging, with the first PFI prison contract awarded in 2006 for the Mine Rehabilitation Promotion Centre. This includes delivering a wide range of services but, like the French and German prison model, private sector providers will not be permitted to deliver face-to-face services. This is a feature also seen in Japanese PFI hospitals, where responsibility for delivering clinical services remains with the public sector. |

|

Evidence of this can be found in the custodial services sector, where prisons were completed on time and within budget as a result of PFI contracts, saving the taxpayer up to £260m between 1991 and 2002.22 Quality of service is a key element considered in the bidding phase and, in the case of Altcourse Prison in Liverpool, the contract went to the bidder who came first in quality evaluations - a private sector consortium. Bridgend Prison in South Wales and Altcourse are also good examples of delivering on time and within budget. For example, on the Bridgend contract, one private consortium's bid cost £50m less than that of a similar public sector scheme.23 The prison also opened five months ahead of schedule, reducing the need to house prisoners in police cells.

EXHIBIT 4 |

|