3.2. Introduction

The acquisition of military equipment is a subject both deeply abstruse and wearily familiar. It is filled with technical detail and jargon, impenetrable to the outsider, yet it is the also the stuff of screaming headlines. "How can it be that it takes 20 years to buy a ship, or aircraft, or tank?" "Why does it always seem to cost at least twice what was thought?" Even worse, at the end of the wait, "Why does it never quite seem to do what it was supposed to do?" And, since this seems to be the stuff of annual recrimination, "Why has the problem endured for so long?" The issue is a mystery, wrapped in an enigma, shrouded in an acronym.

The problems, and the sums of money involved, have almost lost their power to shock, so endemic is the issue, and so routine the headlines. It seems as though military equipment acquisition is vying in a technological race with the delivery of civilian software systems for the title of "World's Most Delayed Technical Solution". Even British trains cannot compete.

Acquisition Reform, as it is generally known, is a subject only about 5 minutes younger than the acquisition of military equipment itself. Within the last 30 years there have been at least three substantial efforts in this direction in the UK, and two in the United States. A hundred years ago the costs of delivering Dreadnoughts were the stuff of newspaper campaigns, and it is likely that 400 years before that Henry VIII's Treasury had rows with the Navy over the cost and lateness of the Mary Rose.

As well as being endemic, the problem is also widespread: each of the UK's Armed Services suffers from it, the UK's allies too report similar problems. Mr Robert Gates, the US Defence Secretary, has recently written a number of papers on poor US experience in this area, in which the words "United States" could be deleted and replaced with the words "United Kingdom" without affecting the sense of the argument one jot. Discussions with France reveal that it has almost identical challenges, and Australia recently concluded an investigation into just this issue.

Others doubtless suffer in silence. While data on the acquisition performance of former Soviet bloc programmes is not readily to hand, it would take a brave soul to bet that their performance was better than that of the UK.

If the problem is deeply rooted and pervasive, it is also a fair bet that any genuine attempt to resolve the problem will be difficult to execute. If resolution of the problem were easy, then surely someone, somewhere would have solved it by now? While there are plenty who comment and some who attempt meaningful changes, there is little evidence of genuine success.

Nonetheless, the Review team would like to pay tribute to the work that the staff in defence acquisition and support have done over many years both in delivering equipment and support to the front line, but also in endeavouring to address / avoid this problem. In what has not always been the most glamorous part of defence, thousands of people have worked extremely hard over many years to deliver what is asked of them.

So perhaps a first question might be, is it really a problem at all, or just a fact of life that must be tolerated rather than resolved? Does acquisition delay fit with death and taxes as a burden that must be borne? And anyway, how much damage does it really cause, beyond some embarrassment to Defence Procurement Officials and Ministers called to answer the charges of the National Audit Office and the newspapers?

Let's start with some facts. For this study, a team from L.E.K. Consulting, a global strategic consulting business, has worked closely with MoD officials to delve deeply into the data within the Ministry of Defence to analyse the position as objectively as possible. From a possible universe of around 150 programmes for which significant data exist, a floating sample of just over 40 where the data are the most complete have been the focus of attention to try to establish patterns.

The overall picture may be familiar, but it does not look pretty. On average, these programmes cost 40% more than they were originally expected to, and are delivered 80% later than first estimates predicted. In sum, this could be expected to add up to a cost overrun of approximately £35bn1, and an average overrun of nearly 5 years.

Moreover, it has not been possible to establish definitively in this study how much of the military capability originally sought was delivered, because that is not easily expressed in quantitative terms, nor is it reliably captured within the MoD's own management information systems, but there is plenty of evidence of de-scoping of capability in the NAO's annual report on major projects (e.g., fewer Astute class submarines, fewer Nimrods).

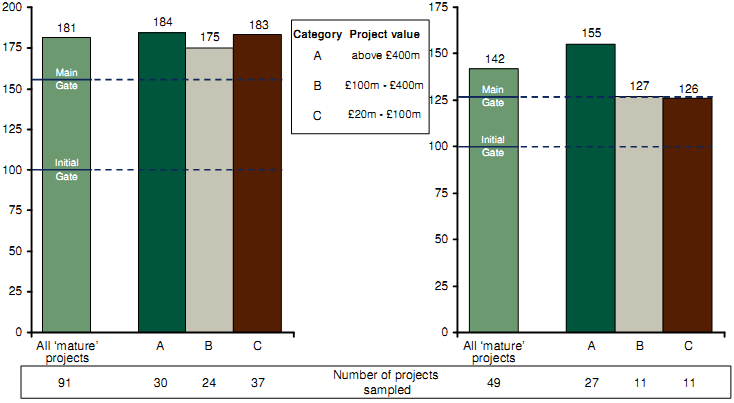

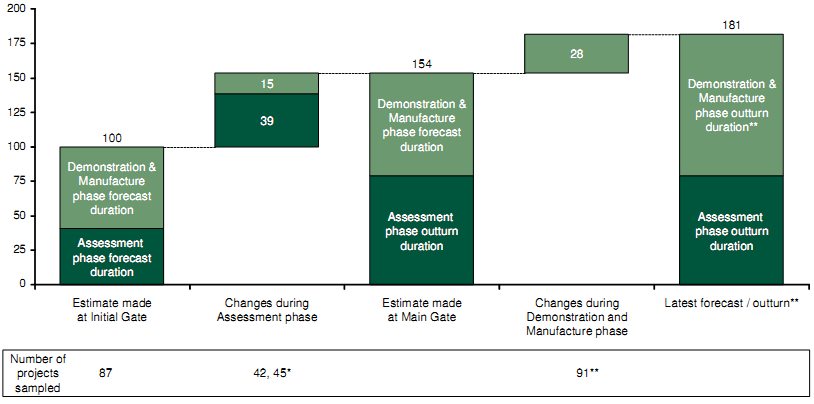

Average growth in project duration (time to "in service") for 'mature' projects**

Index of project duration (Forecast at Initial Gate50 = 100)

Note: * Sample of 42 for Initial to Main Gate forecast and 45 projects for Main Gate to In Service Date; ** Projects over 75% complete and in-service Source: CMIS (Feb 2009); NAO Major project reports; IAB; Review team analysis

Figure 3-1: Average growth in project duration

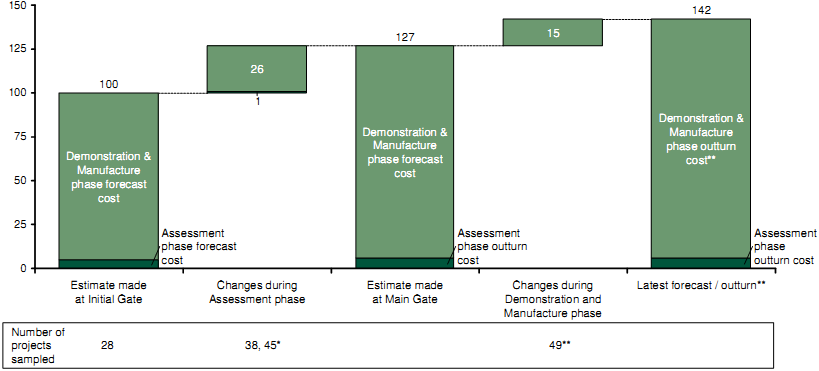

Average growth in project cost for 'mature' projects**

Index of adjusted unit cost^ (Forecast at Initial Gate50 = 100)

Note: * Sample of 38 in the Assessment Phase and 45 in the Demonstration & Manufacture Phase; ** Projects more than 75% complete at latest forecast

Source: CMIS (Feb 2009); NAO Major project reports; IAB; Review team analysis

Figure 3-2: Average growth in project cost

Some suggest that such headline figures are only the result of a few, older "legacy" programmes which have gone badly wrong, and which drag the rest of the portfolio down. This suggestion contains the unspoken assertion that while there may have been problems in the past, that today's management of the position is significantly better. Unfortunately, the facts do not really support such propositions. The analysis of the data suggests that the problems are widespread, affecting projects old and new, large and small to a greater or lesser extent.

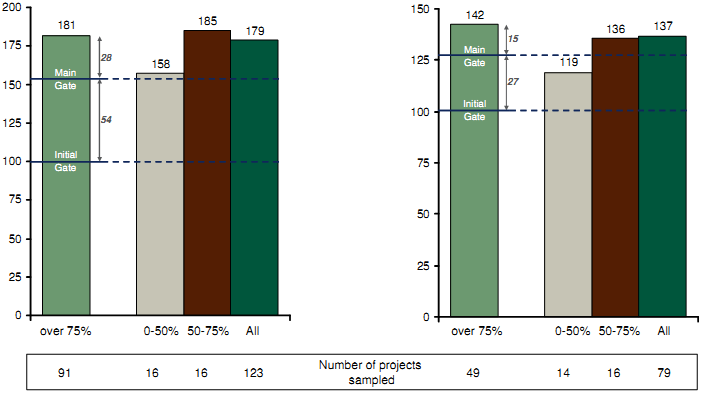

| Latest forecast project duration overrun by Category* | Latest forecast project cost overrun by Category* |

| Index of project duration (Forecast at Main Gate50 = 154) | Index of adjusted unit cost (Forecast at Main Gate50 = 127) |

|

| |

Note: Straight average shown; Projects more than 75% complete at latest forecast; * Analysis of difference by segment is based on growth during D&M phase only

Source: CMIS (Feb 2009); NAO Major project reports; IAB; Review team analysis

Figure 3-3: Project performance by Category

| Latest forecast project duration overrun by Maturity | Latest forecast cost overrun by Maturity |

| Index of project duration (Forecast at Main Gate50 = 154) | Index of adjusted unit cost (Forecast at Main Gate50 = 127) |

|

| |

Note: Straight average shown

Source: CMIS (Feb 2009); NAO Major project reports; IAB; Review team analysis

Figure 3-4: Project performance by maturity

Others say that this overrunning is the result of "defence inflation", the idea that there is something inherent in the acquisition of defence equipment that leads its costs to increase at a faster rate than those of the general economy. It is the contention of the Review team that defence inflation is not a useful concept in explaining the MoD's current predicament. While it is patently true that the unit cost of defence goods is rising rapidly, this does not arise primarily as a result of external cost pressures flowing into defence,

but rather as a result of the behaviours within defence that cause system costs to be inflated. If the issues were tackled within the defence establishment, defence inflation could be better managed.

A stronger argument is advanced that this is an accounting problem: that the system may be poor at estimating what things are going to cost, and how long they will take to build, but this is just a function of poor initial costing, and that the changes merely reflect realism, rather than poor programme control.

There is some truth to this, but the causes are not what they might seem. As well as the inherent uncertainty of future outcomes, and the difficulties of breaking new technical ground, there are less excusable reasons for poor estimates. Simply put, many participants in the procurement system have a vested interest in optimistically mis-estimating the outcome.

The impact of this behaviour is profound, and the knock-on consequences of serious mis-estimation at the beginnings of programmes have a severe impact on the defence programme as a whole.

This weakness at the beginning of new programmes is fundamental, and its causes are critical to the observed outcomes, as this report will make clear. It is imperative to tackle the way in which this system works. If Government fails to tackle this challenge, then the Review team contends that the delivery of equipment will get later and later, that it will become more and more costly, and the UK will ultimately be unable to field the defences it needs.

Others who argue in defence of the current system say that while the data on poor programme performance may be accurate, that other countries' performance is equally bad, and therefore the UK is no worse than the rest of the world in this area. This may also be true. While genuinely comparative data are hard to compile, it is easy to concede the point that the UK is no worse than average. Indeed both French and American officials have been complimentary about the UK's efforts to reform military acquisition over the past decade.

However, the key issue is not comparative. Such overruns are not just accounting entries, but actually cause damage to UK military output - the UK should worry about what it actually does, and not take comfort from the poor performance of others. After all, it would seems a rum argument to assert that being crushed by a falling piano is not really a problem because your friends have also been crushed beside you.

Besides, the UK cannot rely, as perhaps we did during the Cold War, on a balance of delay between Western Powers and any potential adversaries. We are either fighting enemies for whom the delays and bureaucracy experienced by western nations is not a problem, such as in Afghanistan, or we confront new threats which will not wait for our current development timescales to evolve answers, such as the emerging threat of cyber-attack. Those who would attack us in new or unconventional ways are unlikely to wait for our sclerotic acquisition systems to catch up in order to adequately address their threats.

Even within conventional, or traditional, ideas of state-to-state conflict, there is significant evidence that the operation of our procurement system is indeed a real-world problem. The delays to fielding important military equipment have left significant gaps in British military capacity resulting from failure to adequately trade-off military performance vs. cost vs. time. For example, the Type 45 air defence destroyer is indeed a mighty and impressive ship, and within a couple of years it should be ready for its main combat mission.

HMS Daring, the first of the Type 45 Class, is the granddaughter of a cancelled NATO programme, called NFR 90, which was meant to replace our aging and less capable 1970s Type 42 ships some little time ago (there are no prizes for guessing what the 90 stands for). Yet because we have lacked modern naval air defences, had we been tasked with a Falklands-style mission during the past 20 years we would have risked significant casualties, the very significant costs of acquiring adequate equipment at short notice (if available) or the embarrassment of not fighting at all.

Many other similar examples could be cited to make the same point. Our blushes have in part been spared by the fact that we have not generally been called upon in recent years to fight the kind of campaigns that have required the services of some of our most expensive and delayed weapons systems.

Besides, there is worrying evidence to suggest that the problems are not just an endemic burden, but that they are an accelerating problem. There are strong suggestions that the problems of prior years are compounding with the problems of current years to produce an increasing rate of delay and cost increase.

Because cash spending on equipment is limited by budgets in any given year, the way in which this acceleration expresses itself is in an increasing delay to the completion of defence projects, and with a concomitant increase in the total cost of programmes over time.

When faced with such an acceleration, a natural question is to ask when it will start to compound at a catastrophic rate. It is a suspicion held by the authors of this report that several of the defence reviews of the post war era have been designed to cut back output to prevent the defence budget spiralling out of control because of precisely such forces. On this occasion it is not possible to be precise about when the crunch will come this time, but it does not feel very far away.

As well as being increasingly late, the total eventual cost of creating these capabilities is huge. HMS Daring and her sisters will cost £1bn each, a price so high the UK can only afford 6 ships. This level of expenditure is well beyond any other current navy in the world, barring the US and France. As a result, the export potential for this vessel is, to say the least, limited. The continued delivery of these ships at this cost may seem bizarre, but it is entirely consistent with each of the single Services' rational desires to retain as much of the available funding as possible.

Where we have been called upon to use our military capabilities in anger, we have been at risk because our plans have not, in some cases, brought forth the equipment needed for the battle. It is a matter of public record that a large amount of the equipment used by the British Army in Afghanistan has been bought through urgent supplementary budget processes, rather than coming from core army stocks.

That may be at least partly excused by the fact that we had not anticipated fighting this kind of campaign in this kind of terrain when we set our plans. But the UK has now been in Afghanistan for over 7 years, and sooner or later the extraordinary ought to become business as usual. Yet the mainstream programme to equip our land forces does not yet reflect this position.

This introduces another question, is the UK buying the right equipment for our current and future needs? Here there is a tug between the real, gritty, difficult combat missions of today in Afghanistan against enemies who fight in a completely different way to us, asymmetric warfare in the jargon, and the longer-range worry about retaining the ability to fight a well-armed modern state at some point in the unknown future.

There is a real debate to be had about this, and a forum is needed to have it. As John Hutton, the former Secretary of State for Defence, implied in a written statement to Parliament on 11th December 2008, it seems likely that we will need to put more focus on the conduct of current operations such as Afghanistan than the system has managed to achieve thus far. Secretary Gates in the US made a very similar point in his budget announcement of 6th April 2009 when he said "every Defense dollar spent to overinsure against a remote or diminishing risk or, in effect, to run up the score in capability where the United States is already dominant is a dollar not available to take care of our people, reset the force, win the wars we are in, and improve capabilities in areas where we are underinvested and potentially vulnerable. That is a risk I will not take".

This tension is real, and needs to be actively managed. For the UK at least, there is a real concern that being able to try to equip for and conduct current operations, and to fund the development and acquisition needed for long-term retention and regeneration of forces may be too much at current levels of funding. Either we find substantially more money, which, to be polite, seems difficult to imagine in the current economic conditions (and may not even then provide the solution for other reasons, more of which later), or we may be shortly be forced to choose, and the choice will be painful.

So as well as producing equipment late and over cost, there is a concern about whether the system is adapting sufficiently to the changing nature of

combat in the 21st Century. It would seem that the forward planning system has not proved agile enough to adapt to a rapidly changing geo-political situation, and that the slow pace of western defence acquisition systems is harming our ability to confront emerging military challenges, and to conduct difficult current operations.

Or, as one wag, and expert in defence acquisition, recently observed, "the system is failing to produce the equipment we don't need."

To make good the shortcomings of the main equipment procurement programme, the Department has relied on a separate stream of fast-tracked acquisition to meet "urgent operational requirements" ("UOR's") Although we have not examined UOR procurement in detail, the Department's data shows it has broadly delivered specified requirements on time and to budgeted cost. In the face of actual operations, even the most efficient acquisition planning and procurement would leave gaps that would need to be filled urgently. However, given the longevity of current operations, an agile acquisition process would have absorbed more of the extraordinary requirements as they became self-evidently ordinary.

What, then, might be done to improve this situation?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Over the life of projects currently approved at Initial Gate