3.6. Retaining balance between Strategic Defence Reviews

While there were shortcomings in the Strategic Defence Review of 1998, by and large it is still widely viewed as a successful and well-balanced piece of work. What then, has led the situation to deteriorate since then, beyond the failure to update this roadmap?

The biggest single failure of control has been that the demands of those specifying new military equipment have not been adequately managed and related to available resources.

The Equipment Capability Customer was created by the Strategic Defence Review to bring together the teams specifying the future military needs of the Armed Forces in a single "purple" tri-service military structure designed to optimise the equipment acquisition needs of the Forces as a whole.

Unfortunately, this organisation (now the MoD Capability Sponsor) was denied the ability and authority to exercise proper control over its own budgets at that time, and this created a significant weakness in its structure. It was given power to choose what military capabilities it wanted to order, without being charged with the responsibility for balancing the books.

The result has seen the organisation drive ahead in its ambition for new capabilities such as network-enabled combat communications, without requiring it to reduce its demands for other, lower priority capabilities over the entire planning horizon. Unsurprisingly, the result has been a ballooning in the forward equipment plans of the MoD to a patently unsustainable level.

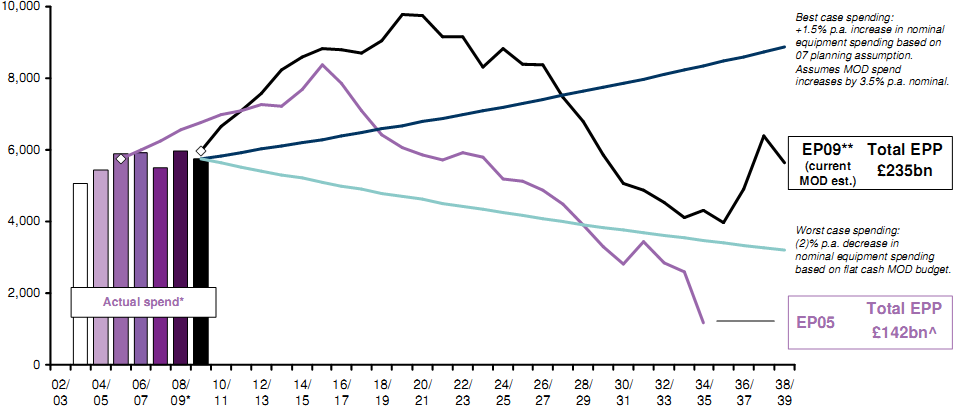

In the past 4 years alone, the future plans for Armed Forces equipment increased by 80 per cent3, before a recent central MoD cost-savings effort reined that escalation back to a more modest 66 per cent3. Neither increase is likely to be affordable on any realistic funding path.

Total Equipment Procurement Plan costs

C DEL + Direct R DEL (Millions of Pounds "Near Cash", nominal)

Note: Includes the cost of the future deterrent, which is subject to separate funding arrangements with the Treasury on the basis (announced in the 2006 White Paper) that the cost of the deterrent will not be at the expense of the conventional capabilities required by the Armed Forces;

* Actual spend not tracked accurately since the formation of DE&S, so control totals are shown for 07/08, 08/09 and 09/10;

** PR09 is after options and manual adjustments (as at 23rd of April), but is not the final EPP. Total PR09 spend includes programme beyond 30-years;

^ EP05total planned spend from 09/10 (no explicit plan beyond 2034/35)

Source: CapEP

Figure 3-5: Total Equipment Procurement Plan costs

As a result of this underlying unaffordability, the Planning Round process (conducted outside and inside DE&S) is also badly broken and urgently needs fixing. Each April the DE&S team enters the new financial year with plans to conduct activity some 10 per cent greater than the available, and known, budget for that year. As a result, a considerable amount of time and effort goes on through the year to reduce expenditure within that accounting year.

Principally, this "re-profiling" involves the delay of activity from the current year into future years, with a number of unsatisfactory consequences. Firstly, it slows delivery of programmes, secondly it obliges DE&S to seek contract variations from industry on already agreed activity. Because the MoD is acting as a supplicant in seeking this change, it has little negotiating leverage over contractors in this matter. This presents industry with a golden opportunity to redress aspects of contracts and pricing it did not like at earlier points, and to hide any shortcomings in its own performance. Inevitably, this process lengthens time and boosts total eventual costs.

Thirdly, it creates pressures that make projects more likely to experience problems. Activities such as technology demonstrators, risk reduction exercises, the holding of financial contingencies against technical risk; all of these sensible precautions are squeezed by the constant downward pressure on cash spending. The result is that more risk is carried later into programmes where it can do more financial damage than if it had been resolved earlier.

This carrying of financial "risk" and the associated "re-profiling" is partially justified by the MoD in the knowledge that delays to expenditure occur and, as with airlines overbooking flights because they know that not all passengers turn up for the flight, this helps cash management of the organisation. While this used to be true, in practice now the pressure of the programme is causing DE&S to have to delay activity which legitimately could be completed in the specified year. This is a highly pernicious and expensive practice that is very damaging to the output of the organisation. It should simply be stopped. The DE&S should simply be required to enter the financial year with an level of activity consistent with its budget, and its DG Finance and Chief of Defence Materiel held accountable to the Defence Board for so doing. If, in the unlikely event of a cash surplus at the end of any financial year, mechanisms can be devised to roll that cash and activity into the following year.

Apart from a general detachment from budgetary responsibility, any attempt by the Capability Sponsor to control ambition is also bedevilled by the demands of the single Services.

Each of the Services quite naturally wants to ensure it gets the maximum share of available resources to allow it to make the best possible contribution to defence. There is nothing wrong in this per se: the range of defence tasks to which any armed force could contribute is always going to be significantly larger than any realistic funding, and it is only natural to want the resources to do more.

Even the United States, which spends over 4 per cent of its huge national income on defence, a much greater proportion than any other western country, still faces significant constraints on what it can do. Medium sized countries, such as the UK, are always going to be more constrained still.

So against a background of potentially infinite demand, each of the Armed Services is competing with each of the others for a share of finite resources. Under these circumstances it is not in any one Service's interest to show restraint in its bids. In a classic Game Theory problem, restraint by one Service is only likely to result in gains for others who do not hold back. Indeed, there is a significant incentive for each of the Services to overbid, expecting the other Services to do the same, and expecting that all will have their bids cut back.

This is perfectly rational behaviour from the perspective of each Service, indeed the Services will feel a moral obligation to specify the best possible solution given that they will be taking people into harm's way, but this process leads to a poor outcome from the perspective of the MoD as a whole. The result is that each of the Services has an incentive to bid for as many different capabilities, at the highest level of specification, that it can.

However, if the "true" cost of acquiring a capability were stated, in a world where resource is tightly constrained, there is a danger that it might be thought too expensive to have at all. Rather than risk a "no" on the grounds of affordability at the outset, from a game perspective it is much better to get the ball rolling on the basis of an unrealistically low estimate, and then deal with the problem of cost growth later.

This is all the more true in a world where once started, programmes are almost never cancelled4. Under current governance, while underestimating the cost of a programme can lead to criticism and delay in the delivery of the required equipment, it is highly unlikely to lead to forfeiture of the desired equipment.

As a result, the forces have an incentive to bid for as many equipments at as high a specification as they can, they also have an incentive to underestimate the cost of delivering this system. This is at the heart of the problem in the UK, and probably the same can be said of other major western powers in the same position. It is the motor that drives delay.

There is, then something approaching an iron law of nature that says that the ambition of any military organisation is, for argument's sake, 25 per cent greater than whatever the level of defence funding available to that country happens to be. As resources expand, so does ambition, as the US example neatly demonstrates. And because this ambition is always going to exceed any level of available resources, the kinds of behaviours noted in this report are likely to occur, driving up the overall eventual costs of the system.

Simply granting the MoD more resources cannot therefore, solve this problem. More resources will probably lead to more military output, but since the ambitions will also expand and the behaviours have not been changed or controlled, the same problems of delay and cost overruns will reassert themselves at the higher level of funding.

These are powerful motivations encouraging each of the Armed Forces to overbid for equipment and underestimate the cost. In part, the creation of the tri-Service Equipment Capability function was designed to try to control these pressures, but in practice this measure has not proved effective. Why?

The MoD Capability Sponsor, as it has now been renamed, is largely composed of officers from each of the single Services who rotate into this joint organisation for a period of time, and then rotate out again to roles within their chosen Service. Their career prospects are largely determined by their seniors within the Service, rather than by defence as a whole.

It does not take much imagination to suppose that each of the Services will make clear to their representatives within the Capability Sponsor what their priorities are, and expect their officers to pursue those goals. Comments received through interviews by the Review team confirm that this is so.

If this pressure to deliver single-Service agendas fails, then above the Capability Sponsor is the Defence Board, on which each of the single Service chiefs sit. So if the head of the Capability Sponsor, the Deputy Chief of Defence Staff (Capability) ("DCDS(Capability)"), passes to the Defence Board recommendations that the individual chiefs do not like, then they can oppose them at the Board. In this role, the single Services appear to have something close to veto power. Certainly, if one chief is implacably opposed to a measure, then it will take unity from the rest of the board to see him off.

The DCDS(Capability) is a senior officer: a three-star Vice Admiral or equivalent, but is nonetheless junior to members of the Defence Board, and not a member of that body. As a result, if several of the 4* members of that board do not care for the plans he brings forward, there is little that one 3* officer can do to object. Besides, as a 3* officer himself, the DCDS(Capability) might still have hopes of promotion, and he is unlikely to make such progress if he is seen to have made life difficult for others.

Even with an independently-minded leader, the odds are stacked against the Capability Sponsor balancing the books. A rough and ready measure says that counting the stars on the shoulders of those admirals, generals and air marshals who can oppose the will of the DCDS(Capability) says that he could stand to lose a fight by 25 stars to 35.

Above the Defence Board sit Ministers, who can also be lobbied if the results of any recommendation from the Requirements community or the Defence Board are not to any individual constituency's liking. Parliament, Industry, the single Services, the science community, Other Government Departments and others all attempt to influence ministerial decisions even after a recommendation from the Defence Board has been submitted for approval.

The permanent structure thus has much to contend with in trying to exercise will and restraint. Even if the Requirements community and the Defence Board recommend difficult decisions, they can be undermined at a later point. This is hardly an incentive for permanent members of the defence community to stand up and be counted against vested interests.

If any significant change is to be achieved, all constituencies, Political, Military, Industrial and Administrative would have to act in the wider national interest. This is a tall order.

This pressure to overbid has other effects. In particular the budgetary pressure forces each of the Services to push to get as much capability as possible, at as low an apparent cost as possible, into each acquired system. This presses those ordering to go for substantial technological leaps in each new generation of equipment.

The Armed Forces, rightly, fear that if they do not get any particular item of equipment specified to as high a level as possible at the beginning, then they will never get additional funding to upgrade a more limited piece of equipment later. All of the incentives within the MoD system operate against the idea of fielding something now and working to improve it over time.

Yet such "spiral" development is widely recognised as being a worthwhile objective that should be pursued. Often, experience with using a piece of equipment will lead to ideas for its further use which could not have been imagined at the time of its original design. Equally, new and previously unimagined technologies may become available that have application in existing systems, if space and money can be found to incorporate them.

As well as offering flexibility, this approach also reduces technical risk, since each step being taken is not as large as the leaps between generations that happens with current equipments. As a result, an initial capability can be introduced into service more quickly, with lower risk, and experience and emerging technologies can guide further development of this tool.

Many senior figures in the military and in industry are keen on this approach, but unless significant steps are taken to substantially reduce the pressure within the equipment programme, it is unlikely to become a viable way of working.

Allied to this question is the issue of how far to pursue capability in any individual area. It is simply unaffordable for the UK to pursue the highest conceivable level of technological sophistication in every area of military equipment. Yet at present, all of the incentives align to encourage the Services to bid for the highest possible capability in all areas in an undifferentiated way. In some cases, it may well be required to have a capability better than any other nation, in others it is not obviously so. The MoD does need better tools for deciding when to accept an "80% solution" to a technical need which is likely to be significantly cheaper and easier to realise than the "100% answer".

In one particular case cited to the Review team, the technology being sought was described as being "just within the laws of physics". While it might be necessary to pursue technologies to such limits sometimes, it is an expensive and risky thing to attempt, and it is important to be clear on whether or not such demanding requirements are really necessary.

If the MoD were able to satisfy itself more often that an "80% solution" were a satisfactory outcome, then it would be able to field more capability, more quickly at lower risk. If it had designed in growth potential, it would also possibly add the ability to upgrade such equipment later. This approach would potentially be good for industry, since in many markets, the costs of the most technologically advanced solutions to military issues are prohibitive. However, it will not be easy to alter the incentives that cause the current overly-demanding situation to persist.

So, sensible processes such as "spiral development" and "technology insertion" are heavily discouraged by the current overheated programme. Development risk (and hence cost overrun / delay) could be reduced by introducing equipment into service, with space allocated within it to introduce more sophisticated technologies later, and to learn from using the equipment rather than trying to guess at all ends before the first of type is ever fielded. But bitter experience shows that any restraint shown in this way will be punished by the loss of uncommitted budget to some other more immediate requirement at a later date. "Bid High Spec, Bid Full Spec", seems to be the encouraged behaviour, however much technical risk that this imposes.

Creating a demonstrably affordable long-term programme would ease these disincentives to incremental development, particularly if the improbable occurred and headroom was left within the programme for future needs with contingency for unexpected overruns.

As well as being substantially outgunned, and subject to powerful forces which tend to over-commit the programme, the DCDS(Capability) does not have all of the tools at his disposal to control the programme. Costs of equipment are not formally targeted beyond a 10 year horizon, despite the fact that many of the most expensive programmes take up to 30 years to complete, and that the MoD can become inextricably engaged in a project well beyond a 10 year plan.

Even within that horizon, the programme is not constrained within affordable limits, programmes that exceed likely funding lines are not tracked, independent cost estimation is a skill which has been eroded over time, and the management information systems and heavy-duty finance skills required to track such a complex programme are not in place.

Sometimes, even when independent cost estimates do exist, their conclusions have not been used in planning the cost of the equipment programme. There is also evidence that some contractually committed costs have been excluded on the hope that they might be avoided: something that would be anathema in a private-sector body. On occasion, the costs of continuing with some core activities have also been excluded from the planning process, because their costs are inconvenient.

One of the most pernicious elements of the system has been left until last. By and large, consideration of the affordability of any individual new piece of equipment is taken in isolation. The debate at all stages of the project's life, from initiation, through main approval through into manufacturing, is all framed from the perspective of having the piece of equipment or not, and the shortfall in capability of the Armed Forces that would arise if the equipment were not procured. The costs of the project are almost always considered from this perspective.

Of course, in general it is better to have something than not. Most of the equipment being proposed is useful, and it is desirable to have it. In an ideal world, one would acquire it all. But the real question is not whether any particular piece of equipment has utility, but rather how it ranks in importance against other possible defence uses of that money.

There is a complex system for trying to determine priorities within the MoD system, but this does not seem from the evidence available to be an effective mechanism in forcing choice. Certainly, when the prospect of cancellation looms, the evidence does not suggest that this is viewed from the perspective of relative priority, rather that the system focuses on the issues arising solely on a case-by-case basis, making decisions hard.

All of this suggests a flawed process in need of significant reform and substantial external scrutiny. Radical and robust measures are required if this system, and its powerful incentives to over-commit, are to be restrained. All of the participants in this system: the Armed Forces, the Civil Service, and Ministers, bear responsibility for aspects of this over-ordering.

The third substantial recommendation of the Review team is then to create a body and a set of mechanisms designed to corral these forces.

It is proposed that an Executive Equipment Committee of the Defence Board should be created to oversee this equipment plan. The composition of the Committee should be as follows: Permanent Under Secretary (Chair), Chief of Defence Staff, MoD DG Finance, Vice Chief of Defence Staff, 2nd Permanent Under Secretary, and no other. There should be no alternate members of the Committee.

To ensure the legitimate voice of the Armed Forces are well heard, both the Chief of Defence Staff and Vice Chief are deliberately included in the Executive Committee charged with determining the plan. The Chief of Defence Staff should have a specific role in prioritising the needs of the single Services. In order that Finance and the inevitable role of resources are heard too, the DG Finance has a pivotal role.

It should be advised on composition of the plan on a quarterly basis by the DCDS(Capability), the MoD DG Strategy, and by a nominated senior representative of the MoD Finance Function.

It should be created and specifically and statutorily charged, under the same statute as creates the Defence Review structure, with creating a 20 year defence equipment plan which is robust and affordable. The measures of affordability should be spelt out clearly, but in simple terms, plans which are incomplete, or which ignore likely costs, or which do not use independent cost estimation, or which exceed the agreed 10 year MoD budget, or which do not contain an appropriate contingency against technical risk, should be deemed unaffordable.

To avoid the charge that legitimate interests are not being taken into account, then the single Services, Ministers, Other Government Department and Industry should be made party to the construction of the plan prior to its adoption by the Executive Committee. The time for debate is prior to the creation or annual updating of the plan, not after it has been assembled, costed and approved by officials.

This Executive Committee should propose to the Defence Board on an annual basis the balanced and affordable equipment plan, which the Board should then be required to endorse or reject in toto, rather than consider in parts. This measure is designed to prevent specific interest groups from attempting to cherry pick parts of the programme that suit its purposes.

The equipment plan should then be presented to Ministers for approval, with the expectation that Ministers too would accept the constraints of the plan. If Ministers are at this stage minded to vary the recommendations of the Board, then the full costs of any such variations should be brought out, and alternative measures taken to reduce the costs of the programme.

In particular the costing of the equipment programme, including all known liabilities, and the assessment of its affordability against the ten year defence budget should be the responsibility of the MoD DG Finance.

In a similar vein to enabling the Permanent Under Secretary to balance the aspirations and resources available to defence in the Defence Review process, the Permanent Under Secretary, in his guise as Accounting Officer, should then arguably be placed under a duty to Parliament to account annually for the affordability of the programme. This is similar to the "going concern" challenge placed upon private sector boards as a legal requirement, and serious sanctions should apply against its breach, as it does for private sector directors.

This is an extremely important test and control, and one that focuses the minds of directors in the private sector. In line with this experience, the

Review team also recommends that this annual equipment plan should be audited by an external body, ideally one of the large accounting firms, to ensure an independent opinion that the plan is affordable within the defined 10 year equipment plan.

While it is not possible to know all ends in the public or private sectors, it is possible to legally require the officers of an organisation to show reasonable foresight in the execution of a plan. So, for example, the exclusion of known contractual costs, or plans which patently exceed agreed funding profiles, would not pass the test of affordability, and the Permanent Secretary should not be able to testify that they pass such a test.

This is an onerous responsibility, but it also confers significant power on the role of PUS. In his critical role of squaring the needs of the Armed Forces, Ministers, and the Civil Service, the PUS is uniquely well placed to play the role of chief executive. A power that says, "I cannot accept this over-cost plan because I am under a legal obligation to balance this budget, and this plan does not balance," is a powerful tool in the PUS's hands.

The combination of appropriately costed defence reviews, a rolling 10 year budget, and a legally constrained Executive Equipment Committee should make significant progress in ensuring that the equipment programme is well balanced and affordable in both the short and the long-term. This will make it much easier for the procurement organisation and industry to fulfil their roles.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

3 EPP PR09 stage 3b vs. PR05 final (£248bn over £140bn); EPP PR09 stage 3b vs. PR05 final (£235bn over £140bn)

4 Less than 5% of projects are cancelled post Initial Gate – projects largely relate to specific capabilities required under defence guidance

5 DCDS(Capability) is a 3* role, 25 stars assumes CDS, VCDS, CGS, First Sea Lord, CAS, CDM