3.8. Time, cost and performance, and Urgent Operational Requirements

At this point, it is worth dwelling on the factors that can be varied in specifying and delivering a defence equipment plan. The three main levers that can be used to change outcomes are to vary time: slowing down or speeding up a programme; to vary cost, putting more or less money into a project; or to change the performance of the equipment, asking for more or less capability from the system in question.

In the mainstream MoD equipment plan, the main variable that is exercised is time. When budgetary pressures arise, as they often do, projects are slowed down, and delivered later, with the military customer deciding not to reduce his required specification. What happens to cost in these

circumstances is that the short-term cash spend is lowered, while the long-term total cost of delivering the project is increased.

This increase occurs because there are continuing overheads associated with the slowed project. Project teams within the MoD and industry remain engaged even though the project has slowed, industry may have significant working capital tied up in production for longer, and older equipment may have to be kept in-service for longer to make good the gap left by the late arrival of new equipment.

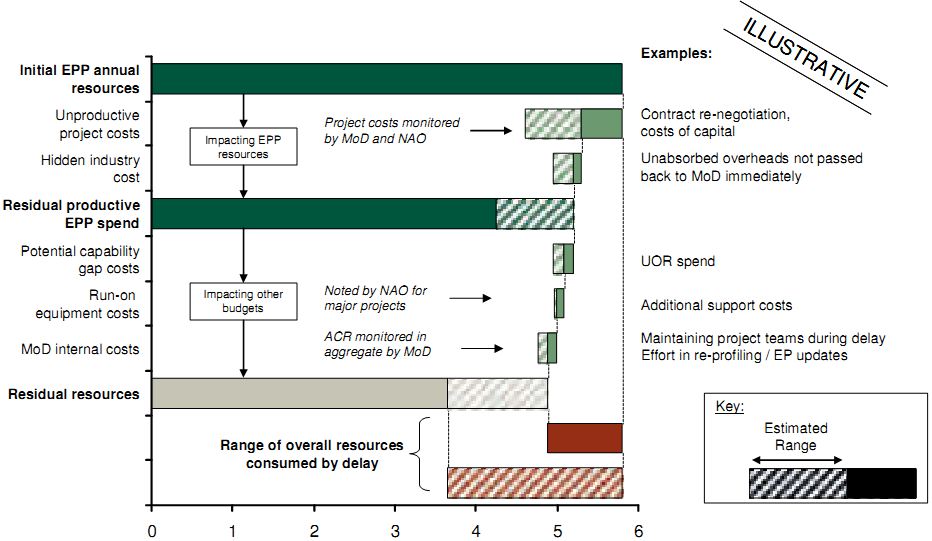

All of these effects serve to reduce the resources available for creating new defence equipment by transferring funds into unproductive overhead. The more this happens, the worse the position becomes. It is impossible to be precise about the exact size of these "frictional costs". In part this is because delay, and its associated costs, can arise for a number of co-incident reasons: for example, a project might hit a technical hurdle which causes delay, at the same time that there is pressure to reduce in-year spend on this project. In such cases there is no one cause for the delay, and so it is not possible to allocate consequent costs to a single factor.

Equally well, there are a variety of different judgements which may legitimately be made in forming a view about such costs. For example, if a piece of equipment is not available as a result of delay, do we ascribe a cost to the lack of availability of this equipment or not? There are also a number of different methodologies which might be applied to calculate these costs, again complicating the position.

The Review team has selected a methodology and made judgements that lead to the numbers in the report. We have concluded from our work that between £1bn and £2.2bn is being lost each year as a result of the failure to control this overheated equipment programme. The wide range estimated by the team bears witness to the fact that this is not a precise science. Further work might refine these numbers, but even with perfect management information, it would never be possible to ascribe a single value to these costs. What is not in doubt is that there are material sums being consumed.

Annual system cost of EPP delays

Source: CMIS (Feb 2009); NAO Major project reports; Review team analysis; DE&S management data; Company annual reports; Press

Figure 3-7: Conceptual system costs of delay - see Appendix G for details

With the financial consequences of delay so significant in the context of the resources available to defence, it is therefore imperative that this telescoping of projects is kept to a minimum. Under current trends, the problem is not only growing, but, based on the Review team's analysis, will grow at an ever increasing rate until more resources are consumed in delay than in producing productive output.

The most interesting lesson arising from the process of emergency purchases of equipment for battle is that priorities between (apparent) cost and time are inverted. For Urgent Operational Requirements ("UORs"), time is absolutely the dominant factor. Other considerations, including the capability of the equipment to meet anything other than the current task become subordinate to the need to field battle-winning or life-saving equipment as soon as possible.

This discipline forces the acquirers of these UORs into tradeoffs that the normal acquisition system avoids. There is not enough time to change one's mind about what capability is required. Compromises are made on the procurement routes, competition and "non-core" requirements. Certainty of price early is better than a theoretically lower price at some time in the future.

It is a fair bet that actually some of the disadvantages of being forced to these tradeoffs are not as bad as they might at first appear. Given the escalation in total costs of mainstream equipment projects, and the additional overheads required, then UORs might turn out to be cheaper to execute than a protracted conventional procurement.

It is worth further reflection about how this time imperative might usefully be employed as a forcing discipline within the mainstream equipment programme.