3.10. Past and future reform of DE&S

The MoD has adapted and changed in remarkable ways. The creation of the Defence Procurement Agency ("DPA") and the Defence Logistics Organisation ("DLO") 10 years ago were remarkable organisational changes that affected thousands of people. The fact that they were achieved within a short period and without major disruption to output was a great achievement.

More recently, the merger of the DPA and DLO into DE&S has also gone outstandingly smoothly. All involved deserve significant credit for managing such change without ceasing to deliver on what was asked of them in the day job.

However, it is the seventh key recommendation of the Review team that further significant actions be undertaken to improve the performance of DE&S. Specific actions should include a reduction in the scope of activities and a restructuring of senior management roles, with greater financial discipline, increased internal accountability for project performance, increased access to / development of professional skills, and increased independence from the Requirements community and the Front Line Commands.

Firstly, the Review team recommends that clarity is needed on what DE&S is for: what its senior management needs to focus on. Currently the range of outputs is wide. This report contends too wide given the challenges.

For example, a number of activities appear to have migrated into DE&S as a result of historical accident and inertia, rather than through planned and deliberate intent. Whilst on the face of it there seems to be some logic in having it all under one roof, it is not clear what real benefits in management or economic terms there are in the range of activities as currently constituted. The Naval Dockyards, the Joint Support Chain and certain aspects of communications infrastructure could useful be hived off into standalone agencies, rather than complicating the structure of an equipment acquisition and support organisation. This would have the benefit of allowing more (appropriately accountable and responsible) senior management effort in guiding the tough job of delivering military equipment capability.

Secondly, even now the senior management structure of the DE&S looks unbalanced. One three star official, the Chief Operating Officer, is charged with oversight of delivery of the whole equipment programme in both initial acquisition and in-service support. By any standards and under any circumstances, this is a Herculean task if the COO is to stand any chance of overseeing such a large and varied programme with any degree of detailed control.

At the same time three other three star officers, the Chiefs of Materiel, have much more limited roles, which are principally involved in liaison with each of the single Services about their needs. The Chief of Materiel roles have made a valuable contribution in the formation of DE&S and have significantly reduced the inherent risk in such a complex merger. However, there is now widespread agreement, which the Review team has heard from many quarters, that these roles should be phased out to significantly reduce the complexity of the DE&S management structure.

There are three other staff roles, Finance, Chief of Staff and Corporate Services, which could usefully be rationalised. As with any other organisation handling significant sums, and DE&S spends around £14bn a year, Finance should have primacy within the overhead structure, and should have equality with the role of service delivery, in this case the COO.

A rebalancing which saw at least one more three star official charged with delivery of the programme, which eliminated the roles of Chiefs of Materiel, and which rationalised the senior management of the Corporate Centre would seem sensible.

Under current circumstances DE&S and industry are struggling to complete an almost impossible task in trying to keep programmes on time and cost. In essence, these delivery parts of the system are required to squeeze a quart into a pint pot, and are working against a constantly shifting target with unrealistic estimates placed upon them as a result of the senior level incentives to over-bid in the formulation of the overall Equipment Plan. It is small wonder that DE&S struggles to deliver, and perhaps a greater one that they do not seek to place responsibility for problems outside themselves.

To temper sympathy for the organisations involved slightly, both DE&S and industry are partly architects of their own misfortune. Cost estimates for programmes are usually created for the MoD centre inside DE&S with input from industry. So to the extent that these initial assumptions are wrong, DE&S and industry are partly responsible.

There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that teams within DE&S come under pressure to minimise the projected costs of programmes by the

Requirements community, keen to get specific projects rolling. It can be hard for individual Integrated Project Team leaders to resist pressure from the centre to produce an "acceptable" cost. The risk is of being characterised as an unhelpful person, "not a team player", or obstructive and negative.

In an organisation such as the MoD, which prides itself on being "can-do", this is a damaging career charge. Where the DE&S team leader is a serving military officer from the same Service as his counterpart in the Requirements community, the charge can escalate to one of failing to deliver their Service's proposed equipment, the charge can be fatal for future prospects.

Unhelpfully in this regard, the role of the independent cost estimation community within DE&S has been reduced over the years, and one of the recommendations of the Review team is that the skills and resources in this area should be increased, as the US is currently proposing to do. There are signs DE&S is planning to do this but the Review team maintains this is a crucial enabler, and one which needs to be properly integrated with the mainstream project and programme management activity urgently.

Industry will also be tempted to look on the potential costs of new programmes with a glad eye. Companies may feel that if they do not produce an acceptable estimate of the cost of a capability when manufacturers are being consulted at the early stage of a project's life, then other competitors may be more obliging at this early concept phase, leading them to have an advantage when it comes time to procure the equipment.

In line with many others, enthusiasts within industry can either deliberately or through mistake minimise the costs and complexities in delivering new technologies. This is unsatisfactory in a number of ways, including giving aid and comfort to a Requirements community seeking to override conservative cost assumptions coming from a DE&S project team.

Yet while one should have at least limited sympathy for the current position of DE&S, the interesting question arises of what would happen if the procurement organisation were asked a more sensible exam question. Could it really deliver a properly costed robust plan?

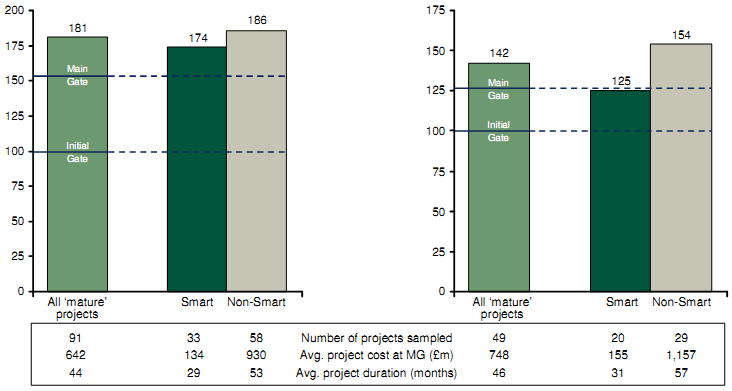

It is impossible to be completely clear on this point, since no such controlled experiment has taken place. But there is some evidence that the Smart Acquisition6 initiative of 1998 has delivered some benefit. Amongst other things, this process sought to clarify the roles and responsibilities of Requirements setters and Acquirers and to empower the Integrated Project Teams to deliver on stable requirements.

Latest forecast project duration overrun by Smart / Non-Smart* | Latest forecast cost overrun by Smart / Non-Smart* |

Index of project duration (Forecast at Main Gate50 = 154) | Index of adjusted unit cost (Forecast at Main Gate50 = 127) |

| |

Note: Straight average shown; Projects more than 75% complete at latest forecast; * Analysis of difference by segment is based on growth during D&M phase only. Non-Smart projects include projects post 1999 deemed to have followed non-Smart principles, e.g. follow on buys of Non-Smart projects Source: CMIS (Feb 2009); NAO Major project reports; IAB; Review team analysis

Figure 3-8: Performance of Smart and Non-Smart projects

Unhappily, some of the clarity which was introduced around Smart Acquisition has been lost in recent years. This is partly through the changes that came with the merger of the Defence Procurement Agency and the Defence Logistics Agency into DE&S. The move to a Unified customer and the new process of "Through Life Capability Management", and its associated Programme Boards, which seek to manage the all aspects of a given military capability across all areas of spending, has also complicated the picture and reduced accountability within the system.

While the aims of the creators of DE&S, the Unified customer and the TLCM are laudable, the risk is that the complexity and group, rather than individual, accountability they encourage may militate against the focus and management control needed to deliver complex programmes.

The challenge, then, is for DE&S to demonstrate it is fit for purpose in delivering a robust equipment plan. There are some areas that this report flags up as requiring significant further progress.

Moreover, while there remains a concern that the professional skills needed in this highly technical area are not always the dominating factor governing the appointment of individuals to management roles. The Review team heard that senior managers do not always have the right to choose those who work directly for them. On occasion, single Services have, for example, imposed candidates who have not always had the required experience or skills onto the DE&S in important delivery roles.

Nor has it been an absolute mandatory requirement that anyone appointed to a senior management role, defined here as being a one-star officer or above, should have significant experience in equipment acquisition or support. It is hard to see how people without that background can guide or control those below them who are required to handle complex programme and project management tasks.

Both of these things should happen: The senior management of DE&S should have the full power to appoint the people they feel most suited to specific tasks, and should be held accountable for those choices. At the same time it should be required in any job description for those holding management positions in the control of significant programmes or projects that they have significant experience of this at more junior levels.

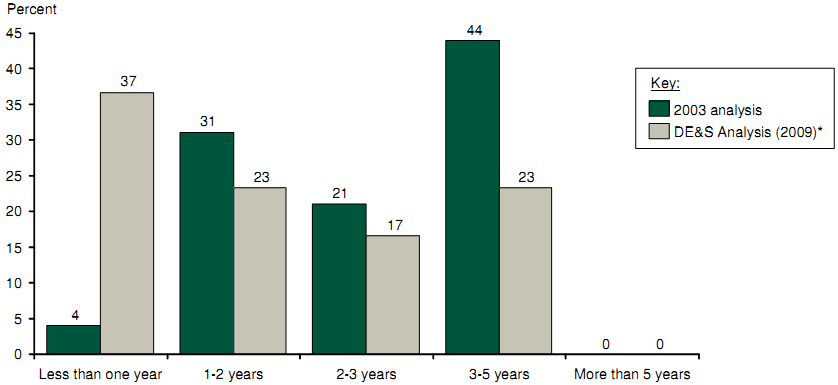

The rapid rotation of managers through jobs was a problem 10 years ago and remains one today. Military officers are required to move every two years to fit in with tour plots and to maintain momentum and breadth in their careers. Civil Servants are increasingly being pressed to follow a similar course.

IPT leader average length of tenure

Note: * DE&S analysis based on initial data from a sample of 30 IPTs (20 post-MG, 10 pre-MG)

Source: McKinsey, 'Exhibits for Final Report of Smart Acquisition Stocktake' (2003); DE&S interviews

Figure 3-9: IPT Leader tenure

These trends are deeply unhelpful to the delivery of long-term projects. Rapid rotation means that corporate memory is lost, accountability is diffused, initiatives are taken in new directions by new managers, and previous plans are "not invented here".

Real and enduring clarity of accountability about who is in charge of a particular programme is also vital. The ability of the DE&S management chain to determine fully its own management team would help accountability and alignment. Longer tenure would ensure consistency of approach and would preserve expensively acquired experience. A requirement for managers to have appropriate procurement and support experience would ensure better project governance. Higher quality teams paid competitive

salaries would allow more migration to and from the wider programme management community in the private sector.

This problem has been highlighted before, and so it is with some trepidation that this report becomes the nth in line (where "n" is a large but undefined number) to recommend change in this situation. It is the recommendation of the Review team that officials and military officers taking line management jobs, defined as IPT Leader or above, in the delivery of new equipment or support should serve double-tours (minimum 4 year terms) in post.

If necessary, mechanisms could be found to assist with promotion problems. More people could be promoted on entry into post, with the explicit understanding that they will serve a double-tour in the role.

Providing military advice from those who need to continue to rotate on a 2-year cycle, or who have no experience of acquisition but whose front line experience is valuable, could be achieved through the appointment of military advisers to IPT Leaders, rather than through someone being part of the line management chain.

Prima facie, there is also a need for more consistent methodology and management tools to be applied across the organisation. A key information consolidation tool used by DE&S is called CMIS, and while it is used for monthly central reporting, it does not appear to be a living, breathing tool within Integrated Project Teams ("IPTs"). IPTs are also free to use whatever programme and project management software tools they wish. The Review team considers that the current management information systems would benefit from standardisation and need further development to facilitate day-to-day delivery by the IPTs.

Shockingly, until recently, there was no mandated requirement as a part of process to have substantial contracts examined and approved by external commercial lawyers before signing. This is a state of affairs that simply would not be tolerated by a private sector company. It is certain that the companies supplying equipment to DE&S will have sought such external, and expensive, legal advice before signing large contracts. It is small wonder that the MoD has struggled at times in the past in attempting to get legal redress for contracts that have gone badly wrong. It is crucial that legal review is implemented.

Comparisons with private sector organisations that also have to handle large project management teams, including for example British Airways and Rolls-Royce, suggest that DE&S teams are large and take a long time to complete their work. BA, for example, would run a competition for a $5bn aircraft order with a full time equivalent team of about 20 people and make the selection within 12 months.

The MoD may argue that such civilian procurements are less particular and bespoke than those in the military, but this is at the least questionable. In the civilian case this team would run the tender process, make a technical and financial assessments of competitive bids, ensure that all of the associated aircrew, cabin crew and technical crew training issues were accounted for, model route selection and the impact of newly acquired aircraft on the existing fleet patterns, and ensure that the appropriate infrastructure, such as hangers, were in place.

Importantly, the team has at its disposal sophisticated financial models that allows it to make trade-offs between different areas of cost. So, for example, if the introduction of a new aircraft type into the fleet would reduce fuel consumption but would increase training and infrastructure bills, then the acquiring team could calculate the financial balance of these issues before making a decision.

It is also critical that one person is empowered to run this process and bring the various different constituencies within the airline to agreement. While it might be possible for one internal interest group to appeal over the head of this presiding officer to the Chief Executive or the board, in practice it is extremely rare for this to happen. As a result, the empowered team leader has considerable scope to run the process efficiently and bring matters swiftly to a head.

Once Heads of Terms had been agreed on a deal, BA would seek to sign the contract itself within 30 - 90 days (for airframes), and certainly no longer than 180 days (for engines), after completion of the negotiations, for fear that the collective memory about what had been agreed would be lost.

MoD processes run much longer than this, with competitions and approvals running for several years, and contracts being signed up to a year after initial contractor selection. The teams lack the kind of sophisticated financial models required to make trade offs between different areas "lines of development" in MoD-speak, and there is no one individual empowered to make such choices. Importing of such private sector tools and skills could make a huge difference to team performance at DE&S.

More qualitatively, there is also a need to raise the skill levels within DE&S on very important and valuable programme management, management accounting, cost estimating, contracting, technical and engineering skills. As with any large organisation, there are many good people doing well, a number of skilled individuals working hard, and some less able individuals who may lack the skills to achieve what is by any measure a difficult objective.

In all of these areas the Review team have heard commentary about the need for investment in skills to produce better results. Strong Programme and Project management skills are scarce in the economy as a whole, and DE&S needs to be able to attract more talent to this area.

It has also been observed that strengthening the contracting skills of the organisation will be required if DE&S is to be able to negotiate the more flexible contracts that may be needed with industry in future.

France has also made a core skill the retention of enough engineering expertise within the DGA, France's equivalent to DE&S, to try to be able to support project teams in delivery of their objectives.

The MoD has acknowledged the need to do more in this area, and a significant amount of effort has been put into this up-skilling agenda. However, pay levels are lower in project and programme management and financial control than comparable roles in the private sector. This makes it hard to acquire fresh skills and fresh thinking from outside the existing organisation.

One senior DE&S official commented to the Review team that it was impossible to hire the skills needed into his specialism because the HR processes within the MoD did not permit the necessary salaries to be paid within standard public sector payscales. Given that £14bn a year, and the future defence of the UK are at stake, and given that team sizes could be smaller with more skilled team members, this seems a false economy, to put it mildly.

None of this is helpful. The organisation needs a single framework for operating so that it is clear to everyone through the structure what is happening. Common operating systems would allow individuals to move more easily from one project team to another, and make a contribution more quickly to their new team. Common project management tools, with proper transparency of information throughout line management would allow overseeing managers to more quickly gauge the health or otherwise of projects. A common legal framework and external review process would strengthen the MoD's hand in dealing with sophisticated contractors.

Sophisticated financial modelling tools would allow teams to make trades between initial acquisition, maintenance, training, and infrastructure costs of different possible systems. More, high quality cost estimators and parametric modelling tools would assist in initial costing.

Development of hard interfaces with both the Requirements community for new equipment and the Front Line Commands for support of existing systems would introduce greater clarity and accountability. If changes are made to requirements by the Requirements team, DE&S should produce a bill that makes clear what the cost of change is. Equally, if the Front Line Commands pay DE&S for a certain level of activity in support, DE&S should account properly for the money it receives from its customers. This will need clear processes between DE&S and the MoD centre, but also effective contracts that allow MoD to change and ultimately retain the ability to cancel projects.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

6 Non-Smart projects include projects post 1999 deemed to have followed non-Smart principles, e.g., follow on buys of Non-Smart projects