Introduction

After years of underfinancing much-needed repairs and maintenance to America's infrastructure-by as much as $2.2 trillion, according to some estimates-digging out of the current deficit will be costly. And with state and local governments facing tight budgets, it may be decades before the work will be affordable. The lack of resources for infrastructure improvement and maintenance extends beyond highways and affects a range of public capital investments, from levees to wastewater treatment and from transportation to schools. The dismal state of the nation's current infrastructure could hamper future growth.

The ways that governments allocate new funding for infrastructure projects and the ways they build, operate, and maintain those projects has contributed to the problem. New spending often flows to less valuable new construction at the expense of funding maintenance on existing infrastructure. Further hindering efficiency, the traditional process for building infrastructure decouples the initial investment-the actual building of a highway, for example-from the ongoing costs of maintaining that highway. As a result, the contractor building the highway often has little incentive to take steps to lower future operations and maintenance costs. Such inefficiencies likely contribute to falling rates of return on public capital investments.

One solution to these incentive problems is to bundle construction with operations and maintenance in what is known as a public-private partnership (PPP). Indeed, many governments around the world are turning to PPPs as a way to tap these efficiencies and to leverage private sector resources to augment or replace scarce public investment resources.

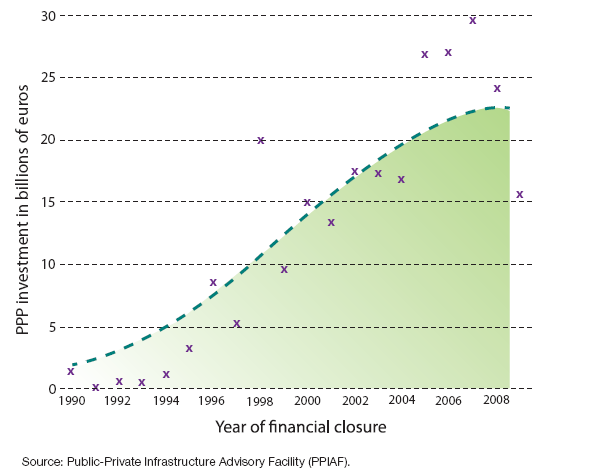

Such partnerships between the public and private sectors have clearly caught on in governments abroad. As Figure 1 shows, PPPs in Europe increased sixfold, on an annual basis, between 1990 and 2005-2006. In certain countries, such as the United Kingdom and Portugal, PPPs now account for 32.5 and 22.8 percent, respectively, of infrastructure investment during the 2001-2006 period (see Table 1).1 While the transportation sector is the largest beneficiary of PPP investments, European countries have used PPPs for projects in defense, environmental protection, government buildings, hospitals, information technology, municipal services, prisons, recreation, schools, solid waste, transport (airports, bridges, ports, rail, roads, tunnels, and urban railways), tourism, and water.

The United States is a relative newcomer to PPPs. Even though there is an old nineteenth-century tradition of privately provided public infrastructure and even of private tolled roads and bridges, the United States still depends almost exclusively on the government for its public transport infrastructure (with the important exception of railroads).2 The two-decade trend toward PPPs that has revitalized the ways that many countries provide infrastructure has gained only little traction in the United States. Whereas the United Kingdom financed $50 billion in transportation infrastructure via PPPs between 1990 and 2006, the United States, an economy more than six times as large as that of the United Kingdom, financed only approximately $10 billion between those years. The use of PPPs to provide U.S. infrastructure increased fivefold between 1998-2007 and 2008-2010, however, in the immediate aftermath of the Great Recession (see Figure 2).

Figure 1 Public Private Partnership Investment in Europe

TABLE 1 Public-Private Partnership Investment in Europe

Country* | Total Investment | Fraction of Public Investment |

Belgium | 2,112 | 3.5 |

France | 7,670 | 1.3 |

Germany | 5,658 | 1.5 |

Greece | 7,600 | 5.9 |

Hungary | 5,294 | 7.3 |

Italy | 7,269 | 2.5 |

Netherlands | 3,339 | 2.2 |

Portugal | 11,254 | 22.8 |

Spain | 24,886 | 6.9 |

United Kingdom | 112,429 | 32.5** |

Source: Blanc-Brude, Goldsmith, and Valilla (2007).

* These are the ten countries with the most investment.

** If the London Underground is excluded, this becomes 20 percent.

MM = millions

High-profile bankruptcies of several partnered U.S. highway projects and swift contract renegotiations of other projects raise concerns about selecting the right projects, hiring the right private partners, and establishing durable long-term contracts.

Drawing on the early PPP experiences in the United States and other countries, this paper proposes several ways to optimize the use of PPPs. Our four main recommendations address best practices-when, where, and how to use PPPs.