5.5. Service flexibility

PPP contracts typically contain a mechanism for agreeing changes during the operating period. If the authority wishes to implement a change, it starts by documenting its request. The contract sets out the circumstances in which the contractor is obliged to meet the request, and the process by which he agrees or disagrees to proceed. Assuming that the contractor has agreed to proceed, he presents cost estimates, and there are then further procedures by which the authority accepts or challenges these estimates until agreement is reached.

PPP contracts are less flexible than non-PPP contracts. Where changes have been implemented across a sector they have been delivered later at PPP facilities. |

All contracts in the survey contained provisions to change the service specification, and these provisions had been used in 50 percent of contracts. Informal changes had also been agreed in 28 percent of contracts, for example changes to opening times or the use of rooms. Interviewees noted that, where the relationship is good, informal changes can be made between the operational staff and periodically swept up into formal variations. All changes were jointly initiated, or initiated by the authority.

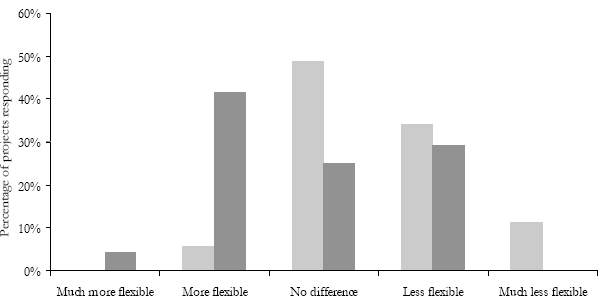

34 percent of authorities considered service levels under a PPP contract to be less flexible than alternative contractual arrangements, for example short-term contracting out, or where the authority itself employs staff to carry out the services. 49 percent thought that the form of contracting made no difference, and only 6 percent considered PPP contracts to be more flexible. By contrast, 42 percent of private sector respondents thought that PPP contracts were more flexible (see Figure 17).

Figure 17: How does the flexibility of service delivery compare with non-PPP arrangements?

Although contracts set time limits for each step of the change procedure, the amount of 'to-ing and fro-ing' between authority and contractor has meant that changes can be very slow to agree. Several authorities stated that it had taken one year or longer to agree what they saw as relatively straightforward changes. The lack of flexibility in the PPP sector was particularly apparent where changes were being implemented across a sector (for example Patient Line in hospitals, or fresh water drinking fountains in schools) and were introduced later at PPP facilities than those operated by the public sector. Concerns about value for money were a significant factor in the time taken to agree changes; authorities often challenged contractors' initial cost estimates and requested additional information. Contractors' perceptions that PPP contracts are more flexible than non-PPP arrangements might result from the fact that there is less need in short-term service contracts than in long-term PPP contracts to include complex change mechanisms.

In interviews both authorities and contractors mentioned that in order to simplify matters, and avoid making changes to the project financial model, they often waited until they could agree a set of changes whose net financial impact would be zero. Refinancing was also seen as an opportunity to push through changes.

Recommendation: Further research should be carried out to look at ways of enhancing flexibility without losing the benefits of PPP, focusing on those sectors where flexibility is a key area (e.g. health).