1. Growing Demands for Infrastructure

■ Rapid and changing patterns of urban population growth:

The urbanization of Canada continues unabated, and nowhere is this more true than in western Canada. In fact, five of Canada's ten fastest growing CMAs over the last 30 years are in the West (Abbotsford, Calgary, Edmonton, Vancouver, and Saskatoon). In the short-term, rapid growth automatically drives the need for more infrastructure. However, it also carries a significant long-term implication in the form of a large future financial liability. For example, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Calgary was booming, and the City borrowed heavily to meet the demand. At the same time, a good portion of the upfront infrastructure costs were carried by developers and the Province. Once completed, this infrastructure was turned over to the City. In the absence of a long-term strategy or anticipatory thinking on the future costs of maintaining, renewing, and eventually replacing the infrastructure, a large future liability is created. For cities like Calgary, the point is brought into sharper focus by yet another boom occurring right now.

An even bigger problem is how this growth is occurring. Much has been written about the devastating effects of urban sprawl and how it dramatically increases the cost of infrastructure. The irony is that while schools and other facilities in the inner cities close due to lack of usage, new facilities need to be constructed in the suburbs. Analysts contend that this pattern of underutilization of existing assets and the need for infrastructure extension will likely continue in the foreseeable future, bringing even more fiscal pressure to bear on local governments (Mirza 2003). In short, sprawl is causing some of the very problems for which solutions are desperately needed.

Even more troubling is the fact that a good portion of urban growth continues to occur in metro-adjacent areas - the urban and rural fringes surrounding Canada's large cities. This presents a particularly daunting challenge in that infrastructure has to be provided to a growing population that pays its property taxes elsewhere. In other words, some western cities are facing significant free-rider problems. Part of the economic rationale behind provincial capital grants was to help offset this negative externality. With capital grants significantly scaled back, this problem has landed squarely on local property taxpayers. However, if taxes are increased in an effort to provide more infrastructure, this could stimulate an even greater exodus toward the periphery, shrinking the tax base and requiring even more punitive taxation. It is hardly a solution. Rather, a vicious circle is created.

■ Infrastructure systems are aging: Much of Canada's public infrastructure was put in place between the end of World War II and the mid-1970s. During this period, public infrastructure was expanding and existing systems were being maintained at acceptable levels (Mirza 2003). Thirty and even fifty years ago, most public infrastructure systems were relatively new and required little maintenance. But infrastructure naturally ages - every system has a definitive lifespan, after which it begins to decay and lose functionality. By the turn of the century, many of these systems began moving to more costly stages of their natural life-cycle, with some components actually reaching the end of their serviceable life. In short, Canada is entering an era where a growing proportion of its public infrastructure is completing its first full life-cycle (Figure 1).

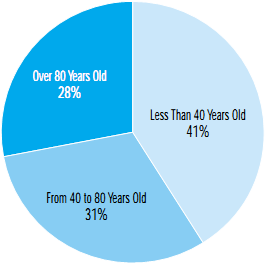

FIGURE 1: Age of Public Infrastructure in Canada

| |

SOURCE: | The Canadian Society for Civil Engineering in a report entitled Critical Condition: Canada's Infrastructure at the Crossroads, 2002. Note that the definition of infrastructure here is not entirely clear, although it includes the infrastructure owned by all orders of government. |

Almost 30% of Canada's total public infrastructure is over 80 years old, and only 40% is under 40 years old. It has also been suggested that Canadians have used, on average, almost 80% of the useful life of all public infrastructure in the country (Canadian Society of Civil Engineering 2002). Thus, aging infrastructure is clearly one reason for the infrastructure deficits facing many cities. An aging public capital stock implies the need for more dollars because older infrastructure is more costly to maintain than new. It also implies the need for better asset management strategies. The natural aging process of infrastructure has been compounded by a lack of previous investment in maintenance and renewal. This "deferred maintenance" has accelerated the aging of infrastructure and its accompanying deterioration, and once deterioration sets in, it continues to compound almost exponentially. Along with escalating costs, the infrastructure becomes more difficult to satisfactorily repair and rehabilitate.

■ Rising standards: Standards have significantly changed over the years, particularly as they relate to protecting the health and safety of individuals and the environment. This has also affected infrastructure. For example, Winnipeg reported an $88 million infrastructure deficit in 1998, but that ballooned to some $188 million in 2003. In part, the increase resulted from a new set of provincial water quality standards and a desire to better protect local water sources. A constant source of friction between municipalities and their provincial and federal counterparts has to do with the fact that those governments often set standards, but then leave the costs of financing them to local governments. Further, increased expectations and the changing preferences of citizens themselves may also be playing a role.

Interestingly, there is debate within many cities regarding locally set standards. For example, the National Guide to Sustainable Municipal Infrastructure argues that standards need to increase, especially as they relate to quality control, installation, and consistency and uniformity in the design, construction and operation of various infrastructure systems. Countering this view, some urban practitioners have suggested that local standards may simply be too high already. It is not meant here that quality control, maintenance, uniformity and improvements should be sacrificed, but rather, the focus may need to shift to issues of functionality and what is realistically affordable as opposed to an unattainable ideal.

■ Lack of correct pricing: Population growth, urban sprawl, and metro-adjacent development are not a conspiracy to financially undo cities. Rather, it is a collective response to current economic trends and incentives. Cities provide a wider diversity of career choices, higher incomes, a higher standard of living, and improved quality of life. Individuals are looking after their own self interest when they move to the city. Further, many of these individuals choose the suburbs and metro-adjacent areas to take advantage of more spacious and affordable housing (Azmier and Dobson 2003). But, this also combines with the fact that many municipal services are under-priced relative to the total costs of providing the service, or are priced incorrectly to individual users (Vander Ploeg 2002a). In other words, there are powerful incentives in play that reinforce locational decisions and increase the consumption of services and the demand for infrastructure.

First, many municipal services are funded by property taxes or a system of centralized financing. Tax revenues are collected, thrown into a pot, and then spread out across a range of services with no financial consequences accruing directly to individuals (Palda 1998a). This leads to the perception that these services are "free." Because costs are shared, there is no incentive to reduce individual consumption, which leads to higher total costs and artificial demands for more infrastructure and services (Groot 1995). To be sure, there are public goods and services that can be financed in no other fashion. But, some argue that the modern city has yielded to confusion between what is really a public good, a private good, and a merit good. Paying with taxes, in whole or in part, for golf courses, libraries, recreation facilities, museums, roadways, and other services may not be the best or most efficient way to proceed (Thomas 1981). While free public roadways have often been seen as a public good, this can no longer be defended across the board given the private benefits that accrue from roads and advances in electronic tolling.

Second, user fees are not always used to accurately price the cost of services, but are often used to simply raise revenue (Kitchen 1993). For some services (e.g., recreation centers and libraries), user fees fail to recover total costs. For other services (e.g., water and sewer), user fees do yield full cost recovery but the price charged is a flat fee that ignores the differential costs of providing the service to specific individuals or properties. Such "average cost" pricing spreads the total costs over a group of users. Only "marginal cost" pricing, where the fee is based on the actual cost of the last unit consumed, serves as an accurate pricing mechanism. Some municipal user fees also do not take into account the additional costs of providing certain services during peak demand periods.

Centralized financing of too many services coupled with user fees that either under-price or incorrectly price other municipal services and their related infrastructure can result in waste, perverse economic incentives, and even cross-subsidization that actually redistributes incomes and benefits. Individuals who consume fewer municipal services, or for whom the costs of providing those services are lower, end up subsidizing those who consume more services or for whom the services are more expensive to provide. If the real nature of this redistribution were known, many would find it unacceptable (Kitchen 1993). For example, taxing everybody so a relatively affluent group can play "subsidized" golf and drive on city roads "for free" does nothing to promote equality of income or the efficient provision of services (Thomas 1981).

As far as infrastructure is concerned, some suggest that the price of developing urban fringe land has been too low - well below the full cost of extending utility and transportation infrastructure and even providing fire and police protection. Some of these costs have been subsidized by taxpayers living closer to the city centre (Thomas 1981). A portion of the infrastructure problem, then, simply relates to current incentives that revolve around cost. Suburban and metro-adjacent properties are less expensive, the real cost of providing those properties with municipal services is not charged to those individuals, and there is good access to "free" urban expressways paid by all. All of this couples with significant demand for the particular lifestyle offered in the suburbs and metro-adjacent areas. In short, there is a powerful set of incentives that encourage growth in the periphery, and part of that relates to the fact that the full costs of living there are not fully appreciated. In all likelihood, this dynamic is more easily tolerated in smaller cities where the differential costs between the centre and the periphery are less obvious. But, the same may not apply to today's large urban centers.