2. Insufficient Funding for Infrastructure

■ Fiscal restraint and recession: The most immediate reason for infrastructure deficits and debt relates to recent fiscal restraint of the federal and provincial governments. Following the huge budget deficits recorded in the late 1980s and early 1990s, these governments began reducing their spending in an effort to end borrowing on the public credit. This period of prolonged belt-tightening occurred on the heels of a rather deep economic recession. Successive federal budgets, which had become increasingly absorbed by high interest payments on debt, were marked by significant reductions in provincial transfers, which eventually found their way to municipalities in the form of less provincial support for both operations and capital.

The result, of course, was a significant fiscal shock for municipal governments. Capital grants, which used to be the financial bedrock for most large municipal capital projects, were severely scaled back, and even today, intergovernmental capital grants tend to be smaller and more sporadic (FCM 2001). Cities are simply more reliant on their own sources of revenue, which tend to be relatively narrow.

During times of fiscal stress, capital spending and the maintenance of assets are the first things to be cut (Parsons 1994). Spending tends to take place where the perceived needs are greatest and the interests are strongest in an effort to avoid any negative public reaction against necessary budgetary measures. In other words, the bridge that needs to be fixed simply waits until next year or the next five years. After all, it is people who protest and not bridges.

Few deny that federal and provincial budgets needed to be brought into balance, but it is important to recognize that this fiscal restraint occurred at a time when cities were growing rapidly and the need for infrastructure investment was rising. While the fiscal deficit has been closed, an infrastructure deficit has opened, and the effect of previous budgetary restraint measures continues to be felt. Relatively high federal and provincial debt levels now limit any significant commitment for a substantial and sizeable re-investment in infrastructure, and could well do so for the foreseeable future (Eggleton 1995).

The current infrastructure dilemma is not just about short-term budget pressures, however. It is also very much about a lack of sustainable and steady investment and rehabilitation over the last half century. A lack of long-term planning has resulted in an ongoing cycle of build and replace that continues to monopolize budgets at the expense of maintenance (Vanier 2000). Some suggest that infrastructure has for too long been considered merely in anti-cyclical terms - as a mechanism to stimulate the economy by increasing aggregate demand. The structural aspect - where investment in the long-term is need to maintain public infrastructure and boost the nation's productive capital - has largely been overlooked. In short, there has been a failure of governments to systematically upgrade their assets. Past investment has been too ad hoc and too unpredictable. There has been no steady program of reinvestment (BDO Dunwoody 2001).

Two examples sharpen the point. First, most municipal infrastructure plans cover a horizon from five to twenty years. But, provincial and federal governments tend to take a much shorter view of things. For example, most of the recent federally-driven infrastructure programs did not stretch past a few years, although the most recent program does cover a ten year period. Second, in the 1970s and 1980s, whenever there was a short-term fiscal crunch, maintenance was always deferred. Again, capital is the first to go. But, maintenance and capital should never be deferred. Investments need to be regular (Comeau 2001). By deferring infrastructure maintenance and renewal, governments are contradicting a fundamental principal of sustainability, namely, that each generation should pay for its share of use and enjoyment of intergenerational assets (Manitoba Heavy Construction Association 1998a).

■ Competing budget priorities: From the 1950s to the 1970s, Canada invested heavily in the infrastructure required for a modern industrialized economy, and governments could afford such investments because the full cost of expanded and enriched social programs such as public health care and education were not yet being felt. After the 1970s, however, regular maintenance of existing infrastructure and new investments had to compete with other priorities that were either unavailable 50 years ago or that had become much more expensive. Today, infrastructure scrambles for the crumbs that drop off the budget table. The debate over whether Canada should have enriched its social programs or engaged in expensive regional development initiatives is well beyond the scope of this effort, but it is obvious that government budgets in 2003 differ greatly from the budgets of 30 years ago.

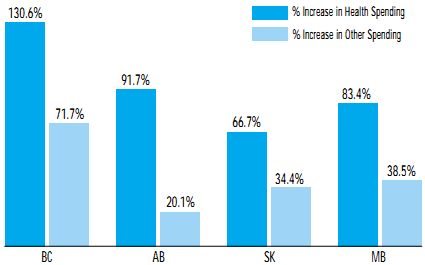

In the current fiscal and political environment, governments remain fixated on tax cuts and reduced public debt, or expanded spending on health care and education. In fact, the bulk of new federal and provincial government spending has been allocated to health care, and to a lesser extent, education. Figure 2 demonstrates how growth in health care spending for each western province from 1990 to 2002 has easily outstripped other government spending by a wide margin.

FIGURE 2: Spending on Health vs. Other Programs

|

SOURCE: Derived by Canada West from Dominion Bond Rating Service (DBRS). |

Health care spending is rising at a rate greater than inflation and it is also consuming an increasing portion of provincial budgets. But infrastructure does not just compete with health care. Some contend that infrastructure cannot easily compete with municipal priorities as well, whether that be police and fire protection, social, community and cultural services, or parks, recreation and libraries. Each of these tends to receive higher priority. For many cities, this is compounded by past federal and provincial downloading and offloading of certain services (e.g., affordable housing), which has added to municipal budgets a list of new competing priorities for limited property tax dollars. The net effect is a chronic deficiency in capital budgets (Poisson 2002).

CONSUMPTION vs. INVESTMENT In 1960, total government sector investment in fixed capital formation was about 20% of total government spending on programs. By 2002, total government investment in capital had fallen to less than 10% of total program spending. This trend may be the result of new priorities emerging since the 1960s, such as public health care, government supported education, and other social programs and priorities. But this is not the whole story. Local government, which has traditionally been the builder in the public sector, has seen its investment in fixed capital formation fall from 37% of municipal program spending in 1960 to about 19% in 2002 (Vander Ploeg 2003). Governments are spending more on consumption-related activities than on public infrastructure, and local governments have not been immune. This pattern is reinforced by the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). For fiscal year 2000, the OECD reported that total public and private investment in Canada was only 14.4% of GDP, well behind Japan, Australia, France, Germany, and Italy. Canada's rate of public and private investment was only a hair above that of the U.K. and the U.S. On the other hand, Canada's total government consumption was one of the highest at 21.4% of GDP. While this was slightly lower than that of France, it was well ahead of our other competitors, including the U.K., Germany, Italy, Australia, the U.S., and Japan (OECD 2002). Whether it is the general North American tendency to consume more and invest less than their European counterparts, or it is the result of specific economic factors that favour consumption as opposed to savings and investment, the fact is that Canada does appear to exhibit a rather high propensity to consume. All of this affects infrastructure investment. |

■ A heavy reliance on the property tax as opposed to tax revenue diversity: Compared to both their American and European counterparts, Canadian cities are heavily reliant on the property tax. In fact, Canada is one among five OECD countries that is the most reliant on the property tax (Smith 1996, MacDonald 2002). In many ways, the property tax tends to work well. The tax base is immobile and stable, and the tax itself is visible. All of this ensures reasonable rates of compliance, consistent and predictable revenues, and accountability (Loreto and Price 1990, McCready 1984, Union of Nova Scotia Municipalities 2001).

With regards to infrastructure, however, an over-reliance on the property tax creates numerous problems. First, a good portion of the infrastructure required to accommodate increased population growth may have to be financed and constructed by cities in advance of receiving any property tax revenue generated from that growth. This may simply be a short-term cash flow problem, and the extent and the magnitude of any "lag time" is unclear. But, some still maintain it can be quite problematic under certain circumstances.

Second, the property tax is relatively inelastic, relying on a narrow tax base that links directly to only one aspect of the economy - real estate. This tax base tends to broaden slowly, and cities often find themselves having to increase the tax rate to compensate for inflation - never mind provide adequate revenues (City of Regina 2001). This, combined with the high visibility of the tax, confronts city officials with a political liability in an era when increasing taxation is quite unpopular. Local governments, fearing a public backlash, have been hesitant to adjust the property tax rate to ensure sufficient revenues, and infrastructure has suffered as a result. In short, rapid economic growth and population expansion drive the need for infrastructure, but Canadian cities have to finance that growth through a tax that generates only marginal increases based on that growth.

With regards to infrastructure, sluggish revenue growth is a "double-whammy." Not only does it create a fiscal gap between revenues and growing demands for infrastructure, it limits the ability of local governments to debt-finance their capital expenditures. When revenues expand at a reasonable and consistent pace, some of that growth can be leveraged with modest amounts of debt without increasing the interest burden relative to revenues. If revenues grow only slowly, the interest that accompanies debt can consume more and more operating revenue, squeezing out other priorities.

Third, at least some of the investment in the capital infrastructure of a city is required to meet the demands of commuters, truckers, tourists, business travellers, and other outsiders. Yet, these individuals do not contribute to the residential property tax base upon which many of these services and the capital stock depend. While the extent of this situation differs between cities, given the current patterns of urban growth mentioned above, they can expect even more problems with such "fiscal disequivalence" brought on by an over-reliance on the property tax.

Fourth, administration of the property tax does not always reflect the variable costs of servicing different properties. For example, residential properties closer to the city core are usually more expensive and carry higher assessed values than similar properties in the suburbs. Yet, the costs of servicing suburban properties and their attendant infrastructure are arguably higher. Properties of similar type are assessed the same regardless of the costs of service provision. Further, differential effective tax rates exist between certain classes of properties. It is generally conceded that multi-family residential properties are taxed at a higher effective rate than single-family residential properties, and commercial and industrial properties are taxed at a higher effective rate than all residential properties (Kitchen and Slack 1993, UNSM 2001, Kitchen 2000). None of this constitutes a direct link between the taxes paid and the costs of municipal services or infrastructure. Again, all of this can promote sprawl and over-consumption while at the same time artificially driving demands for more infrastructure (Kitchen 1993, 2000).

Fifth, an over-reliance on the property tax could constitute a hidden disincentive for cities to invest in infrastructure. Based on a preliminary analysis of the Canada Infrastructure Works Program (CIWP), for every $1.00 spent on infrastructure, up to 44¢ was eventually returned to the three orders of government in tax revenue. The federal government received 22¢, provinces received 17¢, but cities only 5¢ (Manitoba Heavy Construction Association 1998b). Certainly, only the federal government has full fiscal recapture since incomes and other economic activity resulting from infrastructure investment can spill over outside a city or a province. But federal and provincial tax regimes are also more diverse, which helps recapture a portion of the increase in aggregate demand that infrastructure investment produces. While it is far from proven, one wonders whether cities would be more inclined to invest in infrastructure if they had a more diverse tax system that allowed them to better recapture a portion of the returns generated by such investments.

Finally, it is important to realize that the property tax is a capital tax that targets savings and investment - the very fuel that drives the engine of economic growth, innovation, and increased productivity. As such, some economists argue that capital taxes are among the worst taxes possible (Clemens 2002). If Canada does indeed have a problem with over-consumption relative to savings and investment, it is hard not to overlook the potential role that the property tax may be playing.

■ Changing attitudes toward municipal debt: From the 1950s to the early 1980s, borrowing constituted an important source of capital financing for most cities (Vander Ploeg 2003). Beginning in the mid-1980s, however, many cities embarked on a structured program to reduce debt, especially debt supported by the tax base (tax-supported debt). Some cities pursued the goal of eliminating tax-supported debt all together. For some cities, this may have been necessary due to relatively high debt levels. For example, after a spate of building in the early 1980s, Calgary's total tax-supported and self-supported debt reached a point in 1985 where 24¢ of every revenue dollar was going to interest and principal (City of Calgary 1990). But other forces were also at work. There was a general reluctance by cities to borrow at the high interest rates of the 1980s, and the roller-coaster ride of financial markets since then has made debt instruments less attractive (Mirza 2003). Reinforcing these factors was the emergence of a strong public distaste against federal and provincial deficits and debt, which spilled over onto municipal governments.

As a result, many cities began following a "pay-as-you-go" approach for tax-supported infrastructure (e.g., roads, transit). But changing from debt financing to complete "pay-as-you-go" is not an easy task. At the same time that capital reserves and current revenues are needed to finance capital, funds are still tied up to service outstanding debt. As debt is repaid, only small incremental increases in "pay-as-you-go" funding become available from the reduced debt charges. As a result, many cities were forced to lower their investment in capital until sufficient reserves and "pay-as-you-go" dollars became available.