3. Understanding Infrastructure

■ Lack of life-cycle costing and adequate management tools and techniques: Many analysts contend that governments have failed to give full attention to the life-cycle aspect of public infrastructure. There was, and continues to be, little forethought concerning the full costs of maintenance and the time when infrastructure needs to be replaced (Poisson 2002). Instead of considering the commitment needed to maintain infrastructure across its entire lifespan, governments tend to consider only the initial upfront costs of construction. Replacement, which must occur decades later, is an afterthought - someone else's problem. In short, some say that much of the infrastructure problem facing cities comes from a lack of considering system requirements and performance over its entire serviceable life (Mirza 2003). In the past three decades, this trend has also encouraged governments to take on new construction at the expense of properly maintaining existing infrastructure and facilities (Vanier 2000).

The effect of this oversight is serious, and has led to three particular problems. First, governments may have over-built in the sense that they have more infrastructure and facilities than is realistically affordable. This is not to imply that all of the infrastructure is not needed, but it has exposed the fact that governments do lack the resources for sufficient maintenance and repair of what they own. All of this leads to the second problem - an accumulating maintenance deficit. This produces premature renewals of the infrastructure and periodic failures (Vanier 2000). Finally, this ongoing practice of designing and building systems without explicit consideration of the regular investments needed has met up with the inevitable - an aging capital stock. The time for rehabilitation and replacement of significant infrastructure systems has arrived, but governments are finding the fiscal cupboards bare.

In all likelihood, there are a variety of reasons for this oversight. In part, it is the result of a lack of knowledge and important management tools within the public sector, broadly speaking (Vanier 2000). For example, many cities simply do not have the capability, tools, or resources to build an inventory of the infrastructure they own, never mind undertaking a detailed description or history of that infrastructure's condition and the amounts needed to maintain or replace it. This has led to suboptimal repair and rehabilitation strategies - a toxic mix considering the limited funding available in current budgets. A lack of understanding, proper management tools, communication, support, and a sustainable approach to infrastructure management has clearly contributed to the problem (City of Hamilton 2001). The National Guide to Sustainable Municipal Infrastructure, an initiative of Infrastructure Canada undertaken by the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) and the National Research Council (NRC), argues that infrastructure has suffered from a lack of cohesion in departmental decision-making, which in turn has resulted from ineffective choices, silos, and insufficient links between departmental strategies and corporate planning activities (NGSMI 2002). In many ways, infrastructure is an investment. But it is still eventually consumed. That reality is only now coming to the fore.

■ Accounting processes and priorities: In the past, many cities recorded only a portion of their annual capital spending in the consolidated statement of income and expenditures - the full amount spent did not form part of the annual budget balance. Rather, an amount for depreciation or interest on debt to fund the capital was charged to current expenditures. This reflected the fact that capital is an investment, and as such, the costs were spread over the life of the asset. Today, accounting principles in the public sector have changed and typically require all capital expenditures to be fully expensed in the year they are made. This removes a lot of fog from financial statements, but some argue it has also provided a disincentive to spend on capital (Mintz and Preston 1993). If the full value of all capital expenditures are recorded in the year they are made, and a good portion of that expenditure is financed by borrowing, the result is a budget deficit on the consolidated income and expenditure statement. In short, the argument is that today's accounting practices produce a disincentive for infrastructure because fully expensing capital can produce a budget deficit, and the public does not readily understand the difference between a shortfall produced by a large one-time capital expenditure as opposed to a structural operating shortfall. If the pursuit of appropriate fiscal policy means not finishing the year with a deficit (and this is debatable), one way to do that is to relax capital expenditures.

However, a return to past practices is not a long-term solution. Even if the full amount of capital is not expensed annually, debt servicing costs and increased depreciation will eventually be felt. Separating capital from the consolidated budget is controversial because it can alter the government's financial position at year end, and impair the public's ability to judge affordability. As such, a drive must be made to increase the public's understanding of what a "capital-driven" deficit really means.

SUMMARY: Appreciating why municipal infrastructure deficits and debt have appeared is a logical first step before developing any list of potential solutions. Approaches that fail to address the primary drivers of the problem in a meaningful way provide only short-term relief. What is needed are sustainable approaches and alternatives to resolve the matter in the long-term (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3: Addressing the Infrastructure Deficit Drivers

| DRIVERS | GOALS TO BE PURSUED |

| INFRASTRUCTURE DEMAND: |

|

| Population Growth ................ | Change incentives. Urban density. User pay. |

| Aging Infrastructure ............. | Proper maintenance, rehabilitation, replacement. |

| Rising Standards .................. | Emphasize functionality over other factors. |

| Lack of Pricing ..................... | Activity-based accounting. Marginal cost pricing. |

| INSUFFICIENT REVENUES: |

|

| Fiscal Restraint .................... | Long-term planning. Change attitudes to capital. |

| Competing Priorities ............. | Reform other services to free up funds. |

| Property Tax ....................... | Tax diversity to compensate for current incentives. |

| Attitudes to Debt ................. | Combine "pay-as-you-go" with "smart debt." |

| UNDERSTANDING INFRASTRUCTURE: | |

| Life-Cycle Costing ................ | Employ strategic asset managment strategies. |

| Accounting ......................... | Appreciate the unique role played by capital. |

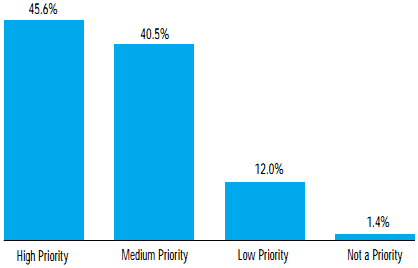

| FIGURE 4: Transportation Infrastructure as a Policy Priority | ||

| QUESTION: | Thinking about what governments can do to ensure the future prosperity and quality of life in your province, would you rate the priority of the following [transportation infrastructure listed as one of the options] as a high priority, a medium priority, a low priority, or not a priority? | |

|

| ||

| SOURCE: Berdahl, Loleen. 2003. Looking West 2003: A Survey of Western Canadians. | ||

|

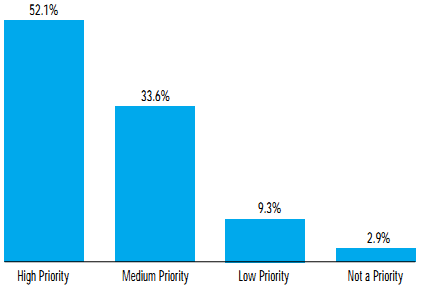

| ||

| QUESTION: | Thinking about what governments can do to ensure the future prosperity and quality of life in your province, would you rate the priority of the following [livable cities listed as one of the options] as a high priority, a medium priority, a low priority, or not a priority? | |

|

| ||

| SOURCE: Berdahl, Loleen. 2003. Looking West 2003: A Survey of Western Canadians. | ||

|

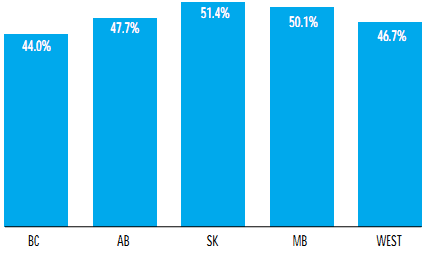

| ||

| QUESTION: | Thinking about your local government, do you feel that your local government has enough, too much, or too little revenue to fulfill its current responsibilities?

| |

|

| ||

| SOURCE: Berdahl, Loleen. 2003. Looking West 2003: A Survey of Western Canadians. | ||

"