PUBLIC OPINION

While uncovering the sources and key drivers of the municipal infrastructure issue are important, so too is an assessment of current public opinion on the matter. If Canadians themselves are not convinced of the severity of the infrastructure problem, they may also be reluctant to explore and consider new alternatives, making the search for potential solutions even more problematic.

■ There is public concern about infrastructure: Recent public opinion survey research demonstrates that western Canadians are indeed concerned about the state of the region's infrastructure. For example, Canada West Foundation's Looking West 2003 (Berdahl 2003) explored the opinions of 3,202 western Canadians. This survey found that almost half of them rated "investing in transportation infrastructure" as a high priority. Almost nine in ten western Canadians rated it to be a high or medium priority for the future prosperity and quality of life for their province (Figure 4).

The survey also asked western Canadians whether or not "ensuring livable cities" was a policy priority, which can be assumed to include at least some aspects of municipal infrastructure (Figure 5). Over one in two western Canadians rated livable cities as a high priority, and over eight in ten rated it as a high or medium priority. Taken together, these data suggest that the public indeed does recognize the importance of infrastructure, and could also be supportive of increasing infrastructure investments.

■ Many believe that local governments lack sufficient revenue: These findings are underscored by yet another question asked of respondents to Canada West Foundation's Looking West survey. Here, western Canadians were asked whether they believe their local government has sufficient revenue to take care of their current governmental responsibilities (Figure 6). Almost one in two western Canadians (46.7%) stated that their local government has insufficient revenues to carry out its responsibilities. Residents of Saskatchewan were the most inclined to hold this position (51.4%), while British Columbians were the least likely (44.0%). At the same time, the differences among all four western provinces are not large. In other words, there is a relative consensus among almost half of westerners that local governments have insufficient financial resources.

■ Other concerns are more important: The challenge for infrastructure investment, however, is not so much that the public fails to recognize it as a priority. Rather, the public identifies a variety of other policy areas as being more important. This is shown by other Looking West survey data highlighted in Figure 7. Again, a majority rated livable cities as a high priority (52.1%) and a near-majority also rated investing in transportation infrastructure as a high priority (45.6%). But, there are eight other policy areas that had more respondents rating them as high priorities. Not surprisingly, these included improving the health care system, protecting the environment, and improving both K-12 and post-secondary education.

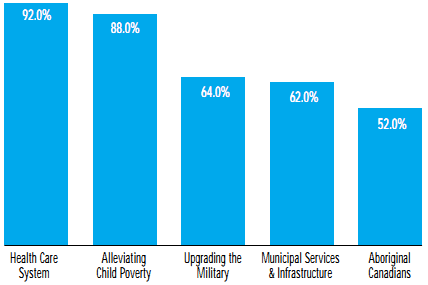

These findings are reinforced from the results emerging from a national 2002 Strategic Counsel survey examining the opinions of Canadians on several policy priorities for government spending. Health care once again topped the list of priorities for government spending with over 90% of Canadians saying that area was important for increased spending (Figure 8). At the same time, over 60% of all Canadians did agree that "municipal services and infrastructure" were an important government spending priority as well.

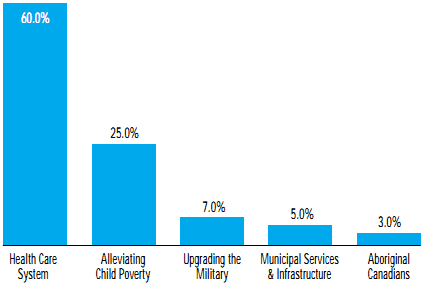

The 2002 Strategic Counsel survey went on to ask Canadians to choose only one policy area as their top priority for increased federal spending (Figure 9). When set against other competing priorities, "municipal services and infrastructure" clearly suffered. Only 5% of Canadians see that option as the first choice among the policy areas presented. Again, health care was the single most important policy priority, mentioned by 60% of survey respondents.

Summary: Canadians do express concern over municipal finance issues in general, and infrastructure issues in particular. But the point to stress is that, when compared to other policy areas, infrastructure investment consistently loses out. It is safe to say that the public does understand the importance of infrastructure in general terms, but its relative importance to other areas is arguably misunderstood. This is a cause for concern because infrastructure is critical to both quality of life and achieving economic potential. Poor or inadequate public infrastructure threatens health and safety, the environment, and the economy. In other words, the tax dollars needed to finance the very priorities of Canadians (e.g., health care and education) do depend to some extent on a good public infrastructure system that supports the functioning of the broader economy.

FIGURE 7: Policy Priorities in Western Canada

(% of Western Canadians Agreeing that Each is a "High" Priority)

| QUESTION: | Thinking about what governments can do to ensure the future prosperity and quality of life in your province, would you rate the priority of the following as a high priority, a medium priority, a low priority, or not a priority? |

| Improving the Health Care System .............................................................................. | 74.0% |

| Retaining Young People .............................................................................................. | 67.6% |

| Protecting the Environment ......................................................................................... | 64.1% |

| Supporting Rural Industries ......................................................................................... | 61.9% |

| Improving the K-12 Education System .......................................................................... | 59.5% |

| Improving the Post-Secondary Education System ........................................................... | 57.1% |

| Diversifying the Provincial Economy ............................................................................. | 54.5% |

| Ensuring Livable Cities ............................................................................................... | 52.1% |

| Investing in Transportation Infrastructure ..................................................................... | 45.6% |

| Lowering Taxes ......................................................................................................... | 41.3% |

| Increasing Aboriginal Employment Levels ...................................................................... | 35.0% |

| Increasing Funding for Social Services .......................................................................... | 31.2% |

| Attracting More Immigrants ......................................................................................... | 13.0% |

SOURCE: Berdahl, Loleen. 2003. Looking West 2003: A Survey of Western Canadians.

| FIGURE 8: Priorities for Government Spending QUESTION: Are the following matters important as government spending priorities? | ||

|

| ||

| SOURCE: | Strategic Counsel Poll conducted in November 2002 and reported in the Maclean's Annual Poll, 2002/2003. | |

|

QUESTION: On which ONE of these would you most like to see increased federal spending?" | ||

|

| ||

| SOURCE: | Strategic Counsel Poll conducted in November 2002 and reported in the Maclean's Annual Poll, 2002/2003. | |

| "SOFT" INFRASTRUCTURE OPTIONS In assessing the range of options for financing municipal infrastructure, it is immediately evident that alternatives tend to fall under two broad approaches: "hard" options that speak directly to increasing the dollars needed to finance infrastructure, and "soft" options that focus on better understanding the issue and seeking savings by following specific strategies, currently within the legislative capacity of cities, that could potentially free existing funds for application elsewhere. ■ Strategic Asset Management: "What is not measured cannot be managed." One of the drivers behind infrastructure deficits and debt is a misunderstanding of the life-cycle demands of existing infrastructure. Proper asset management speaks to correcting this deficiency by creating a clear vision of the "big picture" and what is needed to protect and enhance the performance of existing infrastructure assets. Proper asset management conducted at the macro level attempts to eliminate the disconnect between technical planners and financial decision-makers by breaking down "silos" that work against sustainable asset management and linking strategic infrastructure management across the municipal operation to financial planning. Strategic management of existing assets incorporates six steps that require the production and analysis of specific data to more accurately measure infrastructure needs and manage those needs: 1) An inventory of all infrastructure assets across the municipal operation is constructed (what do we own?); 2) The replacement value of infrastructure assets is determined using current construction costs (what is it worth and what would it cost to rebuild?); 3) The condition and age of existing infrastructure is determined (at what stage in the life-cycle are the assets?); 4) The types of spending required are then determined (what do we need to do - minor or major maintenance, rehabilitation, or replacement?); 5) A timeline is developed as to when expenditures need to be made (when do we need to spend?); and 6) An assessment of the future costs required to preserve and service individual aspects of existing infrastructure assets is conducted (what do we need to spend?) (Vanier 2000, R.V. Anderson and Associates 2002). The data requirements for proper and comprehensive asset management are intense - it demands the collection, production, and analysis of significant amounts of information from across all municipal departments and functions. As such, the process can only be implemented gradually. Some of the best examples of how cities can move in this direction are found in western Canada, and include the 2000 SIRP report of the City of Winnipeg and the work ongoing at Edmonton's Office of Infrastructure. Here, both cities have developed a comprehensive inventory of their infrastructure assets and the replacement value of those assets. Edmonton has gone a step further by thoroughly analyzing the condition of its assets. Work continues on quantifying the investments needed and when they need to occur. The newly created federal Department of Infrastructure is also working to address knowledge gaps as a key element of a more strategic approach through its research and analysis activities. Each of these are significant efforts, and are important steps in achieving a more strategic and integrated approach to municipal infrastructure issues. ■ Regionalize and Rationalize: "If utilization is not maximized, then efficiency is not maximized." Wherever possible and practical, multi-purpose facilities should be considered for a wide variety of public as well as private use. Coordinating infrastructure investments that meet the mutual needs of adjoining municipalities throughout a city-region can be accomplished by collaborative capital planning, shared construction, and shared usage of facilities and its related infrastructure. Such approaches can reduce costs and maximize usage. At the MetroWest II Conference hosted by the Canada West Foundation in 2002, some participants took this option even further, advancing the idea of regionalized service delivery and infrastructure development across western Canada by having various cities develop world class facilities based on existing strategic and inherent advantages. While one city in the West has a world-class international airport serving as a hub for the region, another city would have a state-of-the-art convention centre. As one participant at MetroWest II put it, "Each city in the West should have something, but not necessarily everything" (Vander Ploeg 2002b.) ■ Infrastructure Demand Management: "If costs are to be reduced, then current patterns of usage and behaviour need to change." Managing infrastructure demand and usage through strategies such as "high occupancy vehicle" (HOV) lanes during peak periods, "traffic calming" and the implementation of "reverse lanes" is a basket of alternatives already in play across western Canada's cities. These strategies are intended to manage rapidly growing transportation requirements without expanding existing infrastructure. The effectiveness of such strategies clearly depends on a variety of local circumstances. The intention behind these approaches can certainly be applauded and even recommended, but it is important to realize that they "swim against the current" of certain incentives built-in to the way cities are currently financed. Wherever possible, cities should try and implement strategies across a wide range of services - and the infrastructure supporting those services - that will modify behaviour and usage patterns by using economic incentives as opposed to regulations. For any municipal service that is priced or could be priced, things like "peak period charges" can come into play to limit demand. One example often cited is the establishment of a "bag limit" for solid waste services, and requiring a fee for collecting any amount over that limit (usually by requiring that special tags be purchased for such purposes). |