1. Current Operating Revenue

■ How it works: The largest source of capital financing for most big western cities is a direct internal transfer of current revenue from the operating budget to the capital budget. This revenue stream comprises a significant portion of the funds that are often called "pay-as-you-go" since it takes current revenues earned in one year and applies them directly to the current capital expenditures for the same year. The revenues that are transferred typically include a portion of current property taxes, user fees and other income from licenses and permits, fines, and interest earnings. The prior year's operating surplus is sometimes transferred to fund capital as well.

While it is difficult to sort out specifically, city by city, which current revenues tend to contribute the most to fund capital, it is quite likely that property taxes constitute the single largest source. User fees collected by the operating budget tend to attach to specific services leaving little to transfer from this source. Other revenue, as a portion of most city budgets, tends to be quite small. Thus, any analysis of the potential for current revenues to contribute to the potential closing of infrastructure deficits likely revolves around a detailed discussion of the property tax.

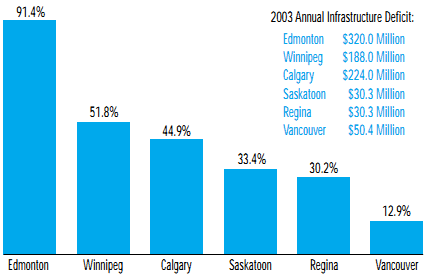

■ Assessing the potential: The infrastructure deficits reported by the cities in 2003 are large relative to property tax collections, and they are growing. For example, unfunded projects in Calgary were $1.120 billion in the 2003-07 period ($224 million a year) compared to $1.375 billion ($275 million a year) in the 2004-08 period. Figure 10 expresses each city's annual infrastructure deficit for 2003 as a percent of the property taxes collected in 2002. If infrastructure deficits were to be closed with property taxes alone, tax revenue would have to double in Edmonton and increase by 50% in Winnipeg and Calgary. Saskatoon and Regina would have to increase property tax revenue by 30%. Even this may be insufficient since Regina's infrastructure deficit amount ignores certain services, and all needs might not have been measured in Saskatoon (Vander Ploeg 2003). Only in Vancouver does closing the gap with property taxes appear even remotely in reach. However, this may be illusory since the Greater Vancouver Regional District (GVRD) provides much of the capital intensive services for the city, and the size of any infrastructure deficit across the larger city-region remains unclear.

| FIGURE 10: Property Tax and the Infrastructure Deficit |

|

|

| SOURCE: Derived by CWF from various city annual reports and capital budgets. |

Increasing property taxes to pay for needed infrastructure is a logical first option. Property taxes do have the advantage of being within the current jurisdiction of cities and there are no legislative restrictions on the amounts by which property taxes can be increased. Some critics of the emerging urban agenda have also argued that cities have created part of the infrastructure problem themselves by intentionally limiting property tax increases through "zero percent tax increase" policies, which are unreasonable and overly restrictive. In other words, the infrastructure problem is to some degree self-inflicted - cities have placed themselves in a revenue crunch that has made it difficult to finance their long-term infrastructure plans.

This argument may have merit if only because zero growth in property taxes should not constitute the final goal of municipal fiscal policy. The property taxes paid by individuals can increase regularly if it grows alongside incomes or some other measure of prosperity. The problem, however, is that conscious decisions to increase the property tax year over year, no matter how small, will not be popular. A powerful barrier to small annual increases is the public perception that property taxes are already too high, although this is far from proven. At the same time, some cities are reporting that growth in property tax revenue cannot sustain the increased costs of municipal operations, let alone deal with capital needs. More important, the property tax has contributed to some of the incentives fuelling infrastructure deficits. Without reform of the property tax system, combined with tools to address free-riding, increasing property taxes may only reinforce these incentives. In the final analysis, property taxes do have some potential. But, the magnitude of the increases required coupled with public perceptions and the current incentives produced by the tax, means that potential may be limited.