7. Borrowing

■ How it works: Infrastructure is a long-term investment that often provides benefits for decades. As such, cities have always issued a certain amount of debt to fund these investments. The debt is either borrowed on financial markets or from provincial municipal financing authorities. The debt is usually in the form of serial debentures (annual repayments of interest and principal over a specified time period) or sinking fund debt (annual interest is paid out of current revenue and amounts are deposited into a sinking fund that collects its own interest and is cleared out when the debentures mature).

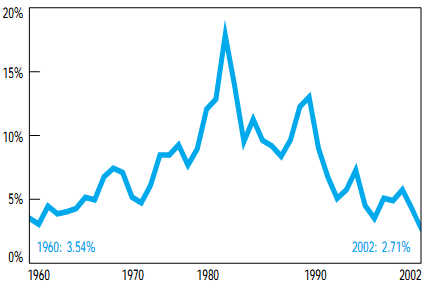

FIGURE 12: Interest Rates in Canada

| |

SOURCE: | Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 11-210-XPB and Statistics Canada Canadian Economic Observer Catalogue No. 11-010-XPB, October 2002 and June 2003. |

■ Assessing the potential: Given that many western cities have drastically reduced their stock of debt since the mid-1980s, there is a certain amount of potential here to address infrastructure deficits by borrowing. This point is underscored by the fact that interest rates are at a 40 year low (Figure 12). For cities that have low levels of tax-supported debt, there could be no better time than now to identify and fund critically needed infrastructure projects by issuing debentures.

Borrowing for infrastructure carries a number of advantages. First, it provides a measure of intergenerational equity in that it allows future generations who stand to benefit from infrastructure to also help pay for the infrastructure through interest and principal costs that will accrue down the road. Total "pay-as-you-go" funding for all tax-supported capital puts the cost on today's generation for benefits that flow well into the future. As such, the issue here is finding a tolerable balance, because complete debt financing also gives the generation building the capital stock a "free ride." Second, borrowing allows desperately needed infrastructure projects to proceed now, as opposed to deferring them until enough "pay-as-you-go" funds have accumulated. Third, debt can be a good financing option if it leverages more capital dollars elsewhere, whether through federal and provincial grants or the private sector.

However, there are also downsides. Excessive borrowing for tax-supported capital can result in higher taxes down the road if the assessment base is not expanding sufficiently. In other words, tax-supported debt may simply defer taxes to some point in the future. Borrowing is also a more costly way to finance infrastructure projects because of the interest charged on outstanding debt, and it also carries a risk in the form of less fiscal flexibility in the future. Steadily increasing levels of tax-supported debt can "squeeze out" other program and future capital priorities, and if debt is relied upon too heavily, it can negatively impact bond ratings, which can result in higher borrowing costs and more difficulty in attracting investment.

Today, the most significant barrier to any increased use of debt is the current mantra of deficit and debt reduction, which makes the option politically difficult. But, the fact remains that there are good reasons for cities to assume modest levels of debt. It needs to be recognized that city budgets are very capital intensive. In 2000, Calgary spent $436 million on capital or 29.4% of its total outlay (Calgary 2000), while the Province of Alberta spent $1.6 billion or 9.2% of its total budget on capital (Alberta 2000). There is a big difference between borrowing for one-time capital projects and borrowing to pay the payroll. Of course, the problem is the public sees little distinction between the two.

Also, a completely debt-free city should not be the ultimate goal of fiscal policy, regardless of how well it plays politically. This is especially the case if the trade-off is an underfunded capital stock. The "pay-as-you-go" approach is arguably better for a city fiscally, but it may not contribute to the overall health of that city, which certainly encompasses more than the balance sheet. Of course, cities need to ensure that debt levels are sustainable and can be tolerated within the operating budget. Intuitively, it would appear that interest costs that consume only 1% of the operating budget (e.g., Saskatoon and Regina in 2002) may be too low.

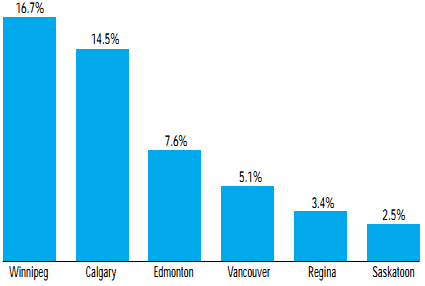

In all likelihood, increased debt is an option that cannot be overlooked, but its potential is limited. First, western cities differ drastically in terms of their debt capacity (Figure 13). Winnipeg spent almost 17¢ of every revenue dollar in 2002 to service its total tax and self-supported debt, and Calgary spent almost 15¢. For most cities, when the costs of servicing total tax and self-supported debt reach above 20% of operating revenue, it tends to become intolerable. In general, only Saskatoon, Regina, and Edmonton have substantial debt capacity. Vancouver appears to have considerable room as well, but the data do not reflect Vancouver's contingent liabilities for GVRD debt.

FIGURE 13: Principal and Interest on Total Debt, 2002

| |

SOURCE: | Derived by Canada West Foundation from individual cities' 2002 Annual Financial Reports and Financial Statements. |

Second, most western cities have already moved to employ this option. Calgary has approved up to $350 million in new tax-supported debt over the next five years, while Edmonton could borrow as much as $250 million. Vancouver voters recently gave approval to almost $100 million in new borrowing, and Saskatoon recently issued $17 million in new tax-supported debt as well. Regina has not conducted any new tax-supported borrowing, but has not closed the option, and the City recently issued $40 million in debt for utility purposes. Only Winnipeg has put the brakes on any new tax-supported debt, reflecting high levels of past borrowing. In other words, a portion of the infrastructure deficits reported by the cities already assume increases in debt.

Of course, the argument can be made that even more debt could be issued. For example, even with the $350 million in new borrowing approved by Calgary, the level of tax-supported debt is still below limits set by Council (the costs of tax-supported debt will be 7.7% of tax-supported expenditure in 2004, below the limit of 10%). But at the same time, it needs to be stressed again that infrastructure deficits are both large and represent an ongoing shortfall. It is unrealistic to assume that financing the entire infrastructure deficit with sizeable and ever-increasing amounts of debt can solve the problem in the long-term, even if debt capacity exists.

Figure 14 projects total debt servicing charges (as a percent of total operating revenue) for each city based on past trends in revenue growth. The model assumes that the entire infrastructure deficit is closed by borrowing, that cities follow through with the borrowing anticipated in their current capital plans, and payments on older debt continue as per current amortization schedules. Within five years, Calgary, Edmonton, and Winnipeg cross a line where 15¢ of every revenue dollar is consumed by debt charges. Vancouver and Regina also show significant upward movement. Only Saskatoon could follow this approach past a five year time horizon, but eventually it too will cross the line.

In short, the use of debt does address a key driver of the infrastructure issue, and it should not be discounted outright. But cities also need to be cautious - debt provides short-term relief, and can likely address only a portion of the problem over the long-term.