7. Innovating With Debt

Much of the innovation in infrastructure finance today revolves around new public borrowing tools and the emerging concept of sustainable, optimal, or "smart" debt. While the merits of these ideas are vigorously debated, it is a necessary step in rounding out any discussion of innovative infrastructure finance.

■ Governments need to explore more avenues: Aside from the traditional municipal debenture are other borrowing mechanisms such as community and tax-exempt municipal bonds. In the U.S., some cities also have access to special state-operated infrastructure banks. The idea behind all of these mechanisms is to either lower the costs of borrowing or to secure improved access to more sources of capital (see pages 26 and 28).

■ Put Canada's AAA rating to use: While most big cities in Canada borrow on their own or through various provincial financing authorities, neither may constitute the least expensive option. First, few cities retain their own AAA rating. The only city in the West that does is Saskatoon. Second, most provinces do not have an AAA rating. The question is, would the creation of a large municipal capital pool through the federal government's AAA bond rating be an attractive option? The idea remains a question at this point because the potential savings are evident, but it is not clear how such a system could be operationalized. At the same time, taking advantage of an AAA rating would lower costs while entailing no significant outlay to either the federal or provincial governments - only loan guarantees.

■ Begin employing "smart" debt: The notion of "smart" debt is increasingly becoming part of the debate over innovative financing. Smart debt recognizes that borrowing is a valid form of infrastructure financing and sets out broad parameters on how cities should borrow. Typically, the idea comprises four components. First, smart debt recognizes that not all capital projects are equally well-suited for tax-supported debt financing. Appropriate candidates include large projects involving substantial sums and that also provide well-defined benefits to the community. Such projects are one-time or non-recurring in nature, they have long asset lives, and can also leverage additional financing elsewhere.

Second, smart debt identifies a sustainable level of borrowing or some notion of optimal debt relative to future operating budgets and anticipated growth. In other words, smart debt requires cities to work through the subjective question of their tolerance for debt.

| COMMUNITY AND TAX-EXEMPT BONDS The borrowing mechanisms open to Canadian cities are generally limited to the traditional debenture issued in the financial market or secured through a provincial municipal lending agency. However, there are other approaches to consider: ■ Community bonds: Here, cities raise a portion of their financing from within the local community. Community bonds recognize that some citizens value the opportunity to help build their own city, and are willing to forego some interest earnings for the sake of making a contribution. Cities benefit from lower borrowing costs, which then leads to lower project costs, which can then lead to lower property tax rates and even more affordable housing (CMHC 1999). If lower borrowing costs help relieve pressure on the local tax base, this would also allow local businesses and firms to become increasingly competitive (Kitchen 2002b). Finally, lower borrowing costs may encourage cities to reduce an inherent reluctance to engage in modest debt financing. ■ Tax-exempt bonds: Tax-exempt bonds (TEBs) are used extensively in the U.S. These bonds can be issued by cities at an interest rate below market value because the earnings to the bondholder are exempt from income tax. From an investor's perspective, TEBs are attractive because of the tax advantage and they are more secure than other investments because they are backed up by a tax base. TEBs are generally seen as predictable, liquid, and offering a good rate of return. Because the take-up rate for TEBs is generally good, cities benefit from greater access to financing at a lower rate of interest which decreases their costs. Some argue that TEBs are more accountable than funding out of the general property tax base because they are issued at the onset of a project and expire when the bonds are repaid (Kitchen 2002b). Others point to how well TEBs are politically received - they have a strong correlation to specific project developments and general economic investment. However, considerable debate exists about the overall merits of tax-exempt bonds. Some argue they disproportionately benefit higher-income earners who can afford to invest and the overall return in terms of tax savings is greater for the wealthy as they are in a higher tax bracket. In essence, government is subsidizing the bond issuer while transferring wealth from all taxpayers to higher income earners via foregone tax revenues. If only certain cities and towns have the ability to issue TEBs, a similar subsidization effect occurs. Some also argue that TEBs can artificially increase the role of the public sector (Bech-Hansen 2002). Finally, transaction fees paid to brokers and bond traders would reduce at least some of the gains that municipalities would receive (Mintz 2002). Most important, financial experts suggest that TEBs could generate significant distortions in the bond market by cannibalizing the investor base for other bonds that are taxable (Bech-Hansen 2002). Several barriers to TEBs in Canada are often mentioned. First, provincial and federal governments would have to amend existing tax legislation and would have to deal with foregone tax revenue (Kitchen 2002b). The market in Canada may not be large enough to support TEBs. Pension funds, RRSP investors, and governments currently hold 65% of municipal debt in Canada, and would likely not invest in TEBs because they cannot realize the tax benefits. This could lower the number of potential investors and actually force the interest rates of TEBs upwards (Toronto Finance Committee 2000). Further, the U.S. market for TEBs is likely larger than Canada's because the U.S. has a lower contribution ceiling for tax-protected retirement investments, which frees up more funds for TEBs as a tax-free alternative (Tuck 2003). The disadvantages and barriers to implementing TEBs are not without their rebuttals. First, the current RRSP program creates a clear benefit for higher-income earners, but that is tolerated because of the importance of ensuring adequate retirement income. Local infrastructure, it is argued, has a similar importance (Bech-Hansen 2002). Any subsidization effects of TEBs could also be offset by significant spillovers in that lower borrowing costs and more and better infrastructure benefits the entire population (Kitchen 2002b). While Canada has higher RRSP limits than the U.S., the value of a TEB tax break is also higher in Canada because of higher marginal tax rates. Finally, proponents argue that distortions in American bond markets do not appear to be an issue (Bech-Hansen 2002). In the final analysis, the merits of tax-exempt bonds are generally clear, but any decision to go that route does involve some significant trade-offs, particularly with regards to questions of equity. In the U.S., those trade-offs are generally perceived as weighing in favour of TEBs. The debate over this financing instrument is a relatively recent addition to the larger debate over urban finance questions in general. At the end of this discussion, a stronger and more clear consensus one way or the other may emerge. |

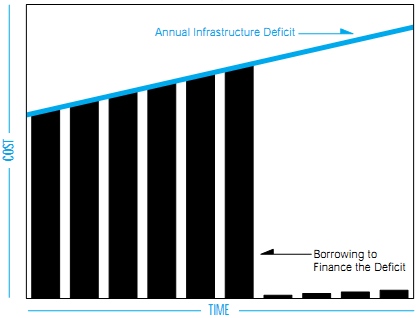

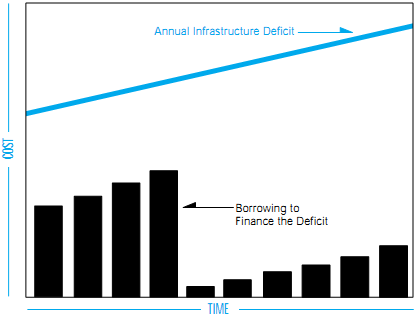

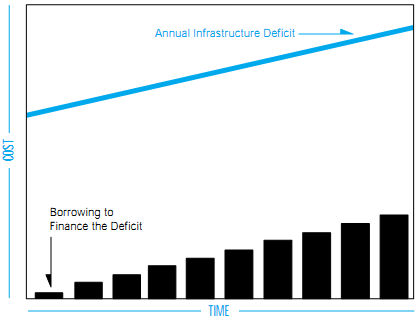

FIGURE 15: Identifying a "Smart" Debt Strategy

An Unwise Approach to Debt Financing the Infrastructure Deficit?

A Better Approach to Debt Financing the Infrastructure Deficit?

The Smartest Approach to Debt Financing the Infrastructure Deficit?

SOURCE: Conceptual options developed by Canada West Foundation.

For example, in February 2002, Calgary implemented a new capital financing policy that allows for up to $70 million in new tax-supported borrowing annually for the next five years. But, strict limits have been set - the cost of servicing all tax-supported debt may not exceed 10% of tax-supported expenditures. In October of 2002, Edmonton also approved a new debt policy. Total debt charges are not to exceed 10% of city revenues and debt charges for tax-supported debt are capped at 6.5% of the tax levy. Debt-financed projects must be worth at least $10 million, have an asset life of at least 15 years, and must fit into approved capital plans.

Third, smart debt sets out policies regarding debt structure and amortization. Such policies speak to the use of serial or sinking fund debt, and structured, retractable, bullet or regular amortized debt. Each carries varying costs and implications. Further, debt amortization terms (e.g., 10, 20, 30 years) are not set arbitrarily or with the sole consideration being lowest cost. Rather, amortization terms reflect the life of the asset. Amortization terms today tend to be in the 10 to 20 year range, but in the past, they have stretched out as long as 30 years.

Finally, smart debt recognizes that debt only finances infrastructure, but the debt itself must be funded. Before issuing debt, cities draw up a comprehensive repayment plan. For example, Calgary implemented a one-time special property tax levy of 1.7% in 1998, which has been earmarked to fund certain borrowings. Edmonton did the same with a special 1% tax levy.

Conceptually, there are three steps to addressing infrastructure deficits. First, growth in the deficit needs to be arrested. Second, the deficit needs to be closed. Third, the accumulated infrastructure debt needs to be addressed. The potential of debt is likely restricted to the first step. Figure 15 shows three options. The first sees the entire deficit (the blue line growing over time) financed in the short-term by debt. Debt levels quickly bump up against a previously set tolerance level and borrowing can grow only incrementally - the deficit reappears and its size continues to grow. Little has been gained. A second approach sees robust borrowing over the short-term after which the pace slows to keep debt levels tolerable. This addresses immediate high priority needs, but may or may not arrest long-term growth. The third approach recognizes that a city can borrow a certain amount each year against an operating budget that tends to grow as well. If borrowing proceeds at a slightly slower pace than even the most modest of growth in operating revenues, then the costs of servicing debt relative to the budget do not rise and debt can be used more effectively over time. This may have the potential to arrest some of the growth in the deficit over the long-term.

SUMMARY: Innovating with traditional capital financing sources does offer potential for addressing infrastructure deficits. However, the innovations do require some significant changes, and the degree to which they will help is not altogether clear. The question is whether spending significant amounts of energy here can really generate a big enough pay-off. More important, the degree to which any innovation will help is highly dependent on how well it addresses the drivers of the infrastructure issue itself. In short, there could be a real need for more systemic reforms.