SCOPE OF P3s ASSESSED IN THIS REPORT

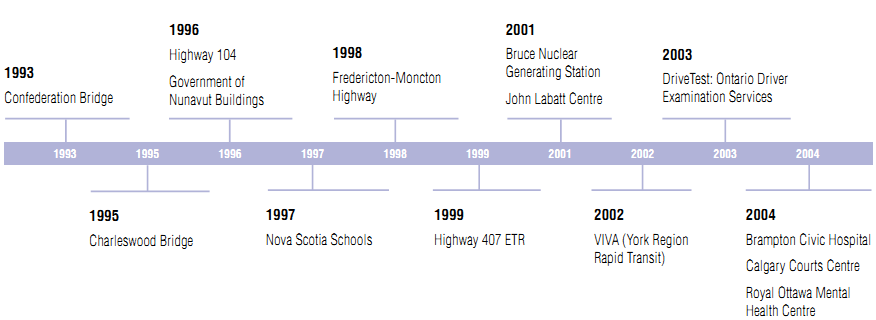

This report focuses on assessing Canadian P3 projects that reached financial close under the direction or guidance of the P3 agencies or the P3 offices located within central agencies or line departments of provincial governments.6 These projects, which we refer to as the second wave of P3 projects, began with the Sierra Yoyo Desan Resource Road, the Gordon & Leslie Diamond Health Care Centre, and the Abbotsford Regional Hospital and Cancer Centre projects, all of which reached financial close in 2004 under the guidance of Partnerships BC. We refer to the P3 projects that reached financial close before the establishment of the P3 agencies as the first wave of P3 projects, as shown in Exhibit 1.

We excluded the first wave of Canadian P3 projects-such as Confederation Bridge, Highway 407 ETR, and the Brampton Civic Hospital-for several reasons. First, many of the P3 procurements chosen in the first wave were initiated at least in part by governments seeking to achieve off-balance-sheet accounting treatment for their infrastructure investments (e.g., Confederation Bridge, Highway 104 Western Alignment), although these accounting treatments have been largely discredited and are now no longer feasible.

|

The first-wave p3 projects did not always succeed in transferring the financing risk to the consortia. |

Second, the P3 transactions concluded during the first wave were quite different from those undertaken during the second wave of P3s. For example, the first-wave P3s usually attempted to transfer revenue risk to the private consortia, while in most second-wave P3 projects the consortia are compensated based on availability payments. Moreover, the first-wave P3 projects did not always succeed in transferring the financing risk to the consortia, while this is standard practice in second-wave P3s. (See box "Lessons Learned From the First Wave of P3 Projects.")

Third, the procurement process for the first wave of Canadian P3s was relatively ad hoc compared with that for the P3 procurements undertaken in the second wave. This is not surprising, since the first wave of projects was undertaken in a period when P3s were a relatively new phenomenon in both Canada and worldwide. Thus, many of the early first-wave P3 projects never had a value-for-money (VfM) assessment comparing the P3 option with a conventional procurement. Even where a VfM assessment was carried out on some of the subsequent first-wave P3s, it was not always done early enough in the process to inform changes in the procurement process. (For example, see the Ontario Auditor General's discussion of the VfM assessment in the Brampton Civic Hospital P3.7)

Exhibit 1 Timeline of P3 Projects Reaching Financial Close-The First Wave of Major P3 Projects

Note: The project year is based on the date of financial close of the project. These projects were drawn from the Canadian PPP Project Directory, but they exclude corporatizations, such as Nav Canada, and projects less than $50 million in value at the time of closing. Note that the three projects listed under 2004 reached financial close prior to the establishment of Infrastructure Ontario and the Alternative Capital Financing Office of the Alberta Treasury Board. Sources: The Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships, Canadian PPP Project Directory; The Conference Board of Canada. |

In retrospect, these lapses occurred in an environment where many public sector owners-from hospitals to cities and even provincial departments-were required to act as their own P3 procurement authorities for the first time (and sometimes their only time). The procurement environment for the second wave of P3s has been markedly different: Most of these P3 projects have been managed, co-managed, or guided through the procurement process by a dedicated public sector P3 agency that has experience with multiple P3 transactions and the benefit of a relatively standardized procurement process, both within jurisdictions and increasingly across jurisdictions as well.

The first wave of Canadian P3 projects has already been reviewed in the literature. In contrast, the second wave of P3 projects has received much less attention. Moreover, while the first wave of P3s continues to provide valuable lessons for public sector owners and private sector participants, a review of the second wave of P3s is likely to provide more timely guidance for P3 procurements going forward.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

6 This is not to suggest that these are the only P3s in Canada. All three levels of government are engaged in P3s of one form or another, such as Windsor Bridge (Transport Canada), Disraeli Bridge (City of Winnipeg), and the courthouse in Saint John (City of Saint John). However, we have focused on the P3 projects initiated by the four provincial jurisdictions, British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec, because these have set up specialized infrastructure agencies (or equivalent offices within central agencies) and because the projects in question are relatively similar in structure, enabling meaningful evaluation.

7 Auditor General of Ontario, "Brampton Civic Hospital."