QUEBEC: AUTOROUTE 25 AND THE MONTREAL SUBWAY EXTENSION TO LAVAL

The Autoroute 25 project was the first P3 project to reach financial close (September 2007) in Quebec, following the establishment of Partenariats public-privé Québec in 2005. We have selected the extension of the Montréal metro to the City of Laval as the case study of a project using a conventional approach to procurement, because it was the only recent major transportation infrastructure project in Quebec that has been the subject of third-party reviews in the public domain. Although outcomes of the two projects are not directly comparable, the two case studies have led to several valuable observations.

First, performance penalties and bonuses can be introduced in conventional contracts, but these will not necessarily force an upfront consideration of all the project requirements, costs, and risks. In this case, the contractor had communicated the under-budgeting to the procurement authority, but either it was willing to bear the penalties from exceeding the budget as a cost of securing the contract (e.g., if the penalties would be more than offset by the additional payments from increased project scope), or the penalties in question were not applicable or enforceable.

|

Cost certainty is an essential part of effective and transparent public sector planning when public funds are at stake. |

The second point is about the importance of cost certainty in budgeting and public infrastructure planning. Cost certainty is not an end in itself. It is an essential part of effective and transparent public sector planning when public funds are at stake. In this case, one could legitimately ask whether the government of the day could have justified a decision to proceed with a budget four times the size of the original budget. In the absence of such a justification-which would usually require a cost-benefit analysis of the project-the government could have chosen to modify the project scope in order to fit a reduced budget or to cancel the project altogether.

The Montréal Subway Extension to Laval- A Construction Management Project The extension of the Montréal subway to the City of Laval on the North Shore was first announced by the Quebec government at a cost of $198 million just prior to the 1998 provincial election. A second order-in-council was passed by the government in June 2000 authorizing a new budget of $379 million for a modest expansion of the project scope (three subway stations instead of two and the addition of an underground maintenance depot). The delivery date for the expansion was set for January 2006. By July 2003, when 90 per cent of the revised $379-million budget had been spent, the government passed a third order-in-council extending the budget to $548 million. A fourth order-in-council was later passed for a budget of $804 million. The project was completed in April 2007 at a cost of $745 million, which was over four times the original budget and 16 months late. This project relied on a construction management approach to procurement, or what is known more specifically as an engineering procurement construction management (EPCM) contract. The EPCM contract was awarded to a leading engineering firm for a fixed fee of $38 million, although it also included a bonus/penalty structure if the project came in under/over budget. The two expert reports that reviewed the events surrounding this project both noted a lack of upfront planning and estimation of the full project costs, as well as a number of other project management and monitoring failures.1 However, it is also worth noting that the bonus and penalty provisions in the EPCM contract did not stop the engineering firm from taking on the EPCM contract, even though it knew the project budget was unrealistically low.2 ____________________________________________________________________________ 1 Québec, Vérificateur Général, "Rapport de verification"; Comité des experts, Rapport du comité d'experts. 2 It was widely known that the original budgets for the project were grossly underestimated. Other comparable subway construction projects in North America had cost between $166 million and $207 million per kilometre according to Pierre Anctil in "Can P3s Effectively Address the Infrastructure Gap." Source: Iacobacci, Steering a Tricky Course, pp. 28-31. |

However, the failure to consider the full costs of the project upfront essentially precluded a rational and transparent approach to the choice of public infrastructure projects. Once a substantial portion of the budget had been spent (and the full financial costs were finally estimated), the money was a sunk cost and the government of the day was poorly positioned to modify or cancel the project. This finding underlines the importance for the public interest of a procurement process that forces an upfront consideration of all costs and risks associated with a project.

|

The additional cost from the discovery of soil contamination is within the range of risks to be rightly assumed by the public sector; it is not usually cost-effective to transfer such risks to the private partner. |

The A25 project is currently under construction, and 40 per cent of the project was completed as of April 2009. However, there have been a number of significant contract variations to date. One of these relates to the cost of disposing of contaminated soil, which was not known at the time the partnership agreement was signed. This risk, which was assumed by the public sector, has turned out to cost $14.8 million. The other variation relates to several modifications requested by the City of Montréal in relation to bicycle paths and wider sidewalks and other cosmetic changes for a total cost of $8.7 million.18

The additional costs resulting from the discovery of soil contamination is within the range of risks that was rightly assumed by the public sector, since it is not usually cost-effective to transfer such risks to the private partner. However, it is less clear why the changes requested by the City of Montréal were agreed to at this late stage.19 These kinds of requirements should be possible to identify in advance of the procurement process through appropriate consultation with the interested parties. Nevertheless, the A25 project remains on schedule and within the original approved budget for the P3 project.

One of the potential future challenges that could compromise the VfM savings from the A25 project on an ex post basis relates to the toll system for the A25 bridge, which has varying toll rates designed in part to manage traffic levels. Should a future provincial government decide to alter the toll policy (to make it more acceptable to the public or to enable coordination of tolling on adjacent roads), some of the toll-related provisions in the partnership agreement might have to be renegotiated. Such an eventuality would constitute an important test of whether the partnership agreement was structured in a way that minimizes future transaction costs related to unexpected negotiations. In general, it is advisable for the public sector to retain control of those aspects of a facility that are subject to a high degree of uncertainty regarding future requirements, because contractual changes can be more expensive to execute under a long-term agreement than under a conventional short-term contract.

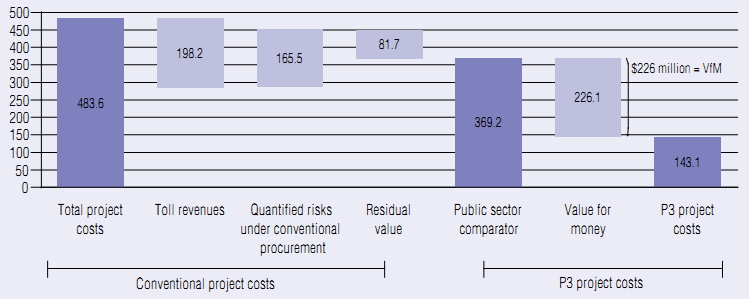

Completion of Autoroute 25 in the Montréal Region-A First Major P3 Project for Quebec The completion of the Autoroute 25 has been in the planning stages since the 1970s, and more recently it has been identified as a priority project under Transports Québec's Greater Montréal Area Traffic Management Plan. The project involves completing a 7.2-kilometre portion of the A25 from Henri-Bourassa Boulevard in Montréal to the interchange with the A440 in Laval, including a new 1.2-kilometre bridge and an electronic toll system with a collection point on the north side of the bridge. The completed link will provide for more efficient road access between the east end of Montréal and Laval as well as the Lanaudière region. It will also reduce congestion on the A40, which crosses Montréal and is currently used by cars and trucks that need to travel between the northeast of Montréal and the Laval/Lanaudière region. A socio-economic cost-benefit study conducted by Transports Québec indicated that the quantified benefits were estimated at more than three times the project costs. Specifically, the ratio was 3.4, which is a clear indication of the need for the project, even after taking into account environmental and road safety impacts. The private sector partner selected through the competitive two-stage procurement was Concession A25 S.E.C., with Macquarie Infrastructure Partners as the equity provider. The contract term is 35 years, including 31 years for operation, maintenance, and rehabilitation of the facility. The partner has the following responsibilities and risks: ♦ design and construction of the facility, including construction cost and schedule risks, commissioning of the facility, selection of the tolling system, and geotechnical risks (the public sector retains responsibilities for any undocumented soil contamination and the acquisition and ownership of the rights-of-way); ♦ operation of the electronic tolling system, including setting the toll rates within the maximum and minimum toll rates prescribed by the agreement. It shares the toll revenue and collection risks with the public partner;1 ♦ operation, maintenance, and rehabilitation of the facility and the tolling system; and ♦ financing. The private partner is paid through an annual availability payment of $13.4 million (without any indexation) beginning at the date of commissioning, with deductions for non-availability of the facility or for other non-performance issues related to maintenance and rehabilitation requirements specified in the agreement. In addition, the private partner receives $80 million staggered across certain construction milestones. The latter payments reduce the financing requirements but do not materially affect the incentives to commission the facility by the scheduled date in the third quarter of 2011. A comparison of the costs of the A25 project under a conventional procurement and a P3 procurement approach is shown in the chart. The public sector comparator (PSC) is calculated starting with the total cost of the project to the public sector over the 35-year term, which was estimated at $483.6 million in 2007 dollars. We then subtract the expected value of the toll revenues ($198.2 million) and add the value of the quantified risks retained by the public sector, which include $68.7 million for cost overruns and $85.7 million for risks related to toll revenues. We also add the residual value of the facility at the end of the contract term, when it is returned to the public sector, giving a PSC of $369.2 million. In contrast, the net cost of the project under the P3 option is $143.1 million, thereby giving VfM savings of $226.1 million, or 61 per cent of the net costs under the PSC. The magnitude of the VfM savings is due to the transfer of risks to the private partner and to the fact that the private partner estimated higher toll revenues than those estimated as part of the PSC (i.e., $198.2 million). ________________________________________________________________________________ Autoroute 25-Project Costs Under Conventional and P3 Approaches (2007 $ millions)

Source: Transports Québec and Partenariats public-privé Québec. Value for Money Report for the Design, Construction, Financing Operation and Maintenance of the Completion of Autoroute 25. _______________________________________________________________________________ 1 The toll system was designed to give the private partner the pricing tools needed to keep traffic levels within a maximum flow of 68,000 vehicles per day, which was a condition of the environmental assessment process. Thus, the private partner can set tolls in excess of the maximum level prescribed by the agreement if actual traffic levels-calculated as an annual moving average-exceed the 68,000 threshold in any month. See The Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships, "Autoroute 25 (Montréal)." Sources: Transports Québec and Partenariats public-privé Québec, Value for Money Report for the Design, Construction, Financing, Operation and Maintenance of the Completion of Autoroute 25; The Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships, "Autoroute 25 (Montréal)." |

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

18 See Radio-Canada, "Dépassement des coûts."

19 According to one source, the City of Montréal was opposed to the A25 project and chose not to participate in the planning. Once the procurement process for the project had been completed, the City of Montréal requested further changes to the project, and these were agreed to by the Ministère des Transports du Québec.