What is the economic cost of the gap?

Although Canada continues to be ranked in the middle of the pack in international surveys, the deficiencies on the infrastructure front are clearly starting to take a toll on the nation's economy. For example, inadequate highways, border infrastructure and public transit have led to increased congestion and considerable lost time to the private sector. In the Greater Toronto Area alone, the annual loss from congestion and delays of goods shipping has been estimated at $2 billion. But, in contrast to the forecasts of the infrastructure gap that have flowed out steadily in recent years, there are no projections on what Canada's infrastructure gap means in terms of total foregone economic activity.

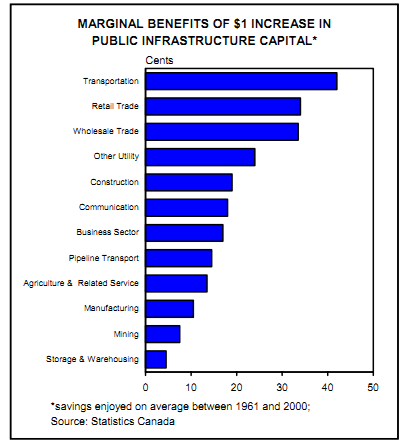

In a study released by Statistics Canada last year, an attempt was made to quantify the marginal benefit of public capital in terms of the cost savings to the private sector from an additional unit invested in new infrastructure.15 It concludes that a one-dollar increase in the net public capital stock generates approximately 17 cents in average private-sector cost savings. Thus, in a scenario where investment had been maintained at a level that would have prevented the $ 100-billion-odd infrastructure gap from opening in the first place, at least $ 17 billion ($0.17 times $ 100 billion) in total private-sector savings would have been enjoyed. As the chart shows, these savings vary from sector to sector depending on the reliance on the public capital stock in the production process. The transportation industry is projected to save more than 40 cents for each dollar of public capital investment.

Keep in mind that these estimates do not take into account the enormous, albeit hard-to-measure, benefits that would be reaped on both the social and environmental fronts from greater investment - lower pollution and fewer safety hazards to name a few. And, there are also intergenerational considerations. Investing in public assets today will yield both assets, and accompanying benefits, that can be carried forward to the next generation.

It is important not to ignore the other side of the ledger, however, since public infrastructure does not come without a price tag. If we assume that the infrastructure gap had not been allowed to open in the first place, an additional $100 billion or more in spending would have been required, of which a large share would have likely been financed. For argument purposes, if we assume that the whole amount was borrowed at a financing cost of 6 per cent, that would yield about $6-$9 billion in higher annual debt-service payments - still well below the $ 17 billion in lower private-sector costs. Under a scenario where offsetting savings could not be found in other areas of government budgets, the increased financing costs would have been funded through higher taxes and user fees, which would also have had some negative economic repercussions. Moreover, there could be other negative effects, such as a decrease in government debt ratings or the crowding out of private investment, which would both place upward pressure on interest rates. Lastly, along with considering the intergenerational benefits, it would be necessary to consider the related debt burden that would be transferred to the next generation of Canadians.