(4) Policy choices exacerbate infrastructure problem

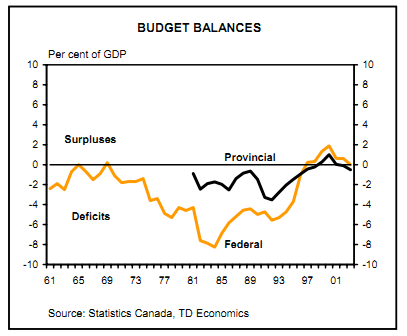

Thus far, the reader may have the impression that a large part of the existing infrastructure gap is due to factors outside the control of governments, such as growth pressures, and the need to combat deficits that were racked up under previous leadership. However, there is little doubt that ill-thought-out policies have aggravated the situation. For one, the quality of management of public assets has been wanting. The useful life of "big ticket" assets - which, as noted earlier, can extend up to 40-50 years or perhaps longer - will be greatly shortened if proper maintenance and rehabilitation are not carried out on schedule. And, while the shortage of available funding has been a barrier to rehabilitating and maintaining existing infrastructure, it is also the case that governments have not made the best use of what little resources they had. Put another way, incremental funding has been heavily geared towards the construction of new assets at the expense of properly caring for existing assets. For example, it has been estimated, albeit not without controversy, that as much as four-fifths of total infrastructure investment in the 1980s was directed at new capital projects.18 This problem of ineffective asset management within government is partly rooted in a lack of knowledge and monitoring of the inventory of public assets. As a result, it is hardly surprising that few governments - particularly at the local level - are able to provide a good estimate of the replacement value of their assets.

FUNDING MODELS • Greater Vancouver's Transportation Authority: partially funded by an 11-cent-per-litre gas tax and a parking sales tax. (Tax rates set by province.) • Victoria: a 2.5-cent-per litre gas tax is collected for transit. • Calgary and Edmonton: receive 5 cents per litre of province's fuel tax. • Manitoba: allocates revenues worth two percentage points of personal income tax and one percentage point of corporate income tax to its cities in form of per capita grant. • Montreal's Agence Metropolitaine de Transport (AMT): partially funded by a 1.5-cent-per-litre gas tax and a $30-per-car registration fee. • Municipalities in Nova Scotia and Quebec: have authority to levy a land transfer tax on the value of transferred property. • Ontario municipalities: to receive 1 cent of the province's gas tax in Oct. 2004, which will rise to 1.5 cents in 2005 and 2 cents in 2006. |

Urban sprawl has not only raised the cost of infrastructure by spreading out provision over a broader area, but it has contributed to increased congestion and pollution, since public transit is not cost-effective in lower-density suburban areas. Although it is natural that the population of downtown areas would grow more slowly than those of the suburbs in light of land availability, the extent of movement has been accentuated by policy choices, particularly at the municipal level. Most importantly, municipalities have subsidized sprawl by not better aligning property taxes, development charges and user fees with the cost of delivering and servicing infrastructure. It is not uncommon to see higher property tax levies on commercial properties relative to residential properties, on high-density residential properties relative to low-density suburban properties, and on downtown commercial properties relative to suburban commercial properties. Undoubtedly, part of the problem of urban sprawl rests with land-planning strategies, which have often been poorly developed, or have not been effectively implemented.

A turn since the late 1990s...

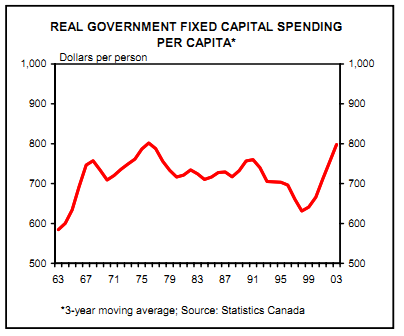

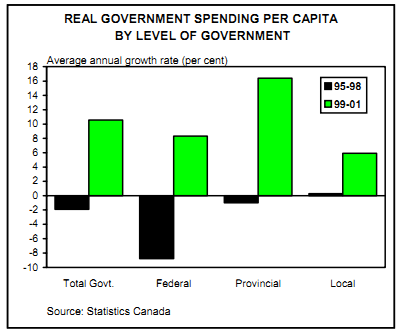

On a high note, as government fiscal positions moved into surplus in the late 1990s, Canadian governments began to inject significant new money into infrastructure. As a result, after slipping in nominal terms between 1992 and 1999, public investment in fixed capital has since surged by about 10 per cent per year.19 Among the jurisdictions, provincial governments led the way, ramping up annual spending to the tune of 16 per cent. Nonetheless, the federal government and municipalities were not far behind, with gains of 7 per cent and 5 per cent, respectively. Across the country, a number of governments jumped on the infrastructure bandwagon. Beginning in the mid-1990s, among other initiatives, the federal government announced a number of infrastructure programs, which were geared largely at assisting municipalities to undertake projects. Moreover, a number of provinces either established capital funds (Alberta and Ontario) or provided municipalities with a share of the gasoline tax or other new revenue-sharing arrangement (see text box).

While brimming revenue coffers proved to be the key sparkplug in setting the infrastructure engine in motion, capital spending also received support from the decision by the federal and most provincial governments to move to an accrual accounting approach for booking infrastructure expenditures - consistent with the approach recommended by the Public Sector Accounting Board (PSAB). This allowed spending to be charged gradually over an asset's useful life rather than in the year of purchase, lessening the near-term hit on the books.

...but already losing steam

While welcome news, the recent five-year spike in capital has not put much of a dent in the overall public infrastructure challenge. Renewed investment has brought real per-capita spending in 2003 back above its late- 1980s level. What's more, the wave of investment witnessed over the past half decade is likely to have done little more than arrest the rate of increase in the infrastructure gap. In order to make real headway in addressing a problem that has emerged over such an extended period an all-out effort would need to be sustained well into the future.

Unfortunately, the wheel appears to be falling off the infrastructure bandwagon, just as it was beginning to round the first bend. In particular, the current round of budgets served up another reminder of the vulnerability of infrastructure spending during tough fiscal times. With fiscal positions turning sour in most provincial governments over the past year, the area facing the chopping block in the 2004 budgets was not health or education operations, but capital spending. In fact, TD Economics estimates that capital outlays will fall in the majority of provinces in fiscal 2004-05, with only a few governments - notably Ontario, Alberta and B.C. - likely to buck the trend. Meanwhile, at the federal level, the government announced that it would exempt municipalities from paying GST - freeing up an additional $700 million per year in local-government cash flow. However, this commitment was only enough to heal the wound inflicted in last year's budget. At that time, the federal government announced a 10-year commitment on infrastructure. That was the good news. The bad news was that the annual spending of $300 million per year fell about $700 million short of the $ 1 billion average annual outlay recorded ex-post between 1993 and 2002. In sum, while this year may prove to be just a temporary setback, the bigger risk is that the most recent upswing in government capital spending will be the exception rather than the rule.