Further tilt towards user-pay model

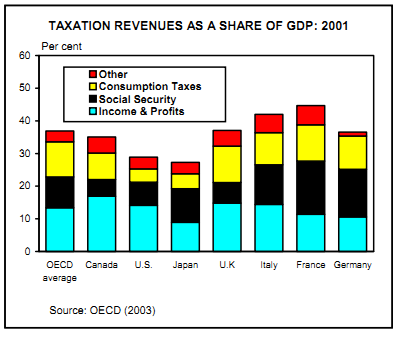

Historically, Canada has relied heavily on raising government revenues through income taxes at the federal and provincial levels and property taxes at the local level. In most respects, their widespread use is warranted. Income taxes remain the best tool to redistribute income from the "haves" to the "have-nots", while property taxes are a stable and accountable revenue source for funding many local services, such as garbage collection and street repairs. At the same time, however, they have their drawbacks. Income taxes, along with capital taxes, create a disincentive to work and saving, and as such, are among the most damaging to economic growth. In contrast, as we indicated on page 7, property taxes are highly regressive, and don't tend to grow in line with the cost of service delivery overtime.

While we would argue that both taxes must always remain a fundamental part of the tax-raising equation in Canada, too much of anything is rarely optimal. And, undeniably, Canada has among the highest income and property tax burdens in the world. On the flip side, Canada has a relatively low consumption-tax burden compared to our international competitors other than the United States and Mexico. Thus, a re-balancing in the tax mix would not only make Canada more competitive, but bring us closer into line with most other countries.

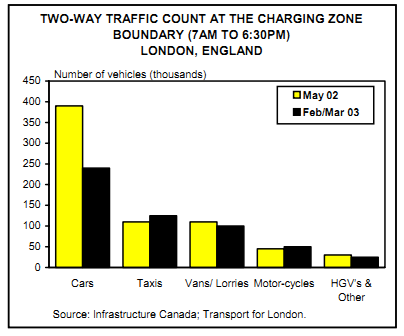

Charging for a service based on consumption offers many advantages. Since by design, user-pay leads to less waste, it is the most efficient approach to revenue raising. This is particularly the case when the level of the rate is set at the full marginal cost of delivering a service including the amounts for both replacement and impact on the environment. In addition, they pass the tests of accountability, transparency, and horizontal equity. Lastly, given the direct impact of these types of consumption levies on behaviour, they can be very useful to governments in achieving their public policy goals. Case in point is the congestion charge implemented last year in London, England's downtown, where traffic flows subsequently fell by a larger-than-expected 15 per cent compared to before the levy was implemented.21 To be sure, this outcome would not have materialized had the government not invested heavily in public transit before the launch and effectively integrated its transportation and economic development strategies. Nonetheless, it lays out a good example of how a user fee played a major role in achieving an end.

User fees are already widely applied in Canada. And, their relative importance has been rising since the late 1990s, especially since the federal and most provincial governments delivered cuts to income taxes in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Still, it remains the case that many governments are failing to put much effort into aligning the price of a service with the marginal cost of delivery. In simple terms, user fees work the best on those services where consumption can be closely measured (i.e., such as water, sewers, electricity and garbage collection). Other areas may be off limits. For example, imposing user fees in areas such as health care or where use is heavily-concentrated among low-income individuals is unlikely to fly. And, for those services where consumption can not be readily measured (i.e., parks, street lighting, and police protection), funding should come through the tax system.

Above all, an area in which user fees have been particularly under-utilized in Canada is in non-public transit. With the exception of a few cases - such as highway 407 in Ontario and the fixed-link bridge in P.E.I. - roads and bridges bear no charges at all, despite congestion ranking high among the concerns of citizens. Around the globe, governments are using new technologies to impose tolls on highways and traffic in downtown city cores. Canada has been slow to exploit these opportunities. Although road tolls are not viable in many cases - for instance, a certain scale is needed to justify the cost of setting up and administering the toll - technological innovations are helping to knock down the barriers related to cost. In fact, the U.K. government expects that the emergence of satellite-tolling technology in vehicles will allow it to charge all private automobiles (in both urban and rural areas) within the next decade.22 There are also other forces at play. For example, the use of road tolls in many cases would be made more manageable if there is an alternative route available for the public with no charge or if the levy is being applied to a newly-constructed road or bridge rather than an existing one.

Charging private automobile users for the full cost of travel would result in considerable benefits for government coffers. The main argument for subsidizing public transit - which is still the practice in most large cities - is to make it cheaper for individuals than private automobile use. But, with more complete costing of private transit use, there would be less of a case for subsidizing public transit on an ongoing basis once initial investments are made to enhance its attractiveness as an alternative. Government coffers would reap a double benefit, freeing up funds for, say, other infrastructure.

Finally, some Canadians might condemn toll and other user fees as an additional tax on residents. However, the old adage "there is no such thing as a free lunch" applies. There are only two ways in which the government can pay for any new development or up-keep. It can either tax all the residents of the area, whether they use the particular infrastructure system equally or not or the government can impose targeted user fees, thereby creating more transparency in usage and cost. Regardless, the public must pay and if given the choice, most would probably opt to control their expenditures through user fees rather than a more hidden structure embedded in property or income taxes.

MORE INNOVATIVE USES OF EXISTING MUNICIPAL TOOLS • Earmark property tax increases, with funds dedicated to infrastructure projects that have strong and widespread support. • Institute special area taxes or cascading charges to reduce urban sprawl. For example, levies could rise gradually in tandem with distance from the downtown core. • Implement additional development levies for "offsite" costs and future maintenance to capture the full cost of infrastructure in the area. • Application of front-end development charges to allow infrastructure to proceed in advance of development. • Charge differential development fees based on the density. • Charging differential fees for non-residents where users can be easily identified. • Creation of new self-financing utilities out of tax-based services to free up room in general tax base for other purposes. Source: Canada West Foundation: "No Time to be Timid", February 2004. |