Local governments need more control over their own destinies

As has already been discussed, many of Canada's municipalities are not making optimal use of their existing, albeit limited, tools and powers. Reforming tax systems, pricing services more in line with their cost of provision, better application of land-planning strategies to reduce sprawl, coordinating services across municipalities in order to enjoy economies of scale, and improved management of their billions of dollars of asset inventories are all on the "to do" list. Furthermore, there may be other creative ways that municipalities could make better application of their current arsenal. In the Canada West Foundation Report, No Time to be Timid, a number of different and innovative ways that existing revenue tools can be applied are discussed, some of which are shown in the accompanying text box.23

In our view, better and more creative use of the funding vehicles currently at their disposal will only go so far in providing municipalities with the flexibility to tackle their massive infrastructure challenges. Over the past few years, TD Economics has issued a number of reports that have touched on the need for a new revenue deal for municipalities. Notably, our April 22, 2002 Report, A Choice Between Investing in Canada's Cities or Disinvesting in Canada's Future, compares and contrasts a number of potential arrangements. In short, the arrangement needs to:

• Provide long-term reliable funding;

• Provide more fiscal flexibility, including increased tools;

• Raise accountability, be transparent and administratively efficient

The report looked at a number of revenue options. The first option, increasing grants, could play a valuable role in helping cities cope with their near-term infrastructure needs. But, they fail in other areas. First, they are weak in reliability, since they leave local governments at the whim of shifting priorities and fiscal fortunes at the federal and provincial level. And, second, they are poor in terms of accountability, since funds are raised by one government and spent by another. At the same time, revenue-sharing arrangements, whereby a portion of a tax collected in a broader area is distributed to the region's governments, are for all intents and purposes, grants. Once again, the link between spending and revenue-raising is broken, increasing the probability that the funds will not be put to the best use.

We believe that it is better to provide municipalities with a revenue arrangement that provides greater flexibility, specifically more power to levy taxes, and in which local governments have control of the rate setting. From a purely administrative perspective, the tax should piggyback off an existing federal and provincial tax base. And, given the problems inherent in administering an income tax at the city level, a consumption-based levy would be preferable, such as a gasoline tax levied within a commuter area. And, while the optimal way to guard against an increase in the overall tax burden would be for the federal or provincial governments to free up the room by cutting their respective taxes, it must be recognized that in order to prevent federal and provincial budget balances from deteriorating, the revenues would need to be made up through another tax increase or spending cut.

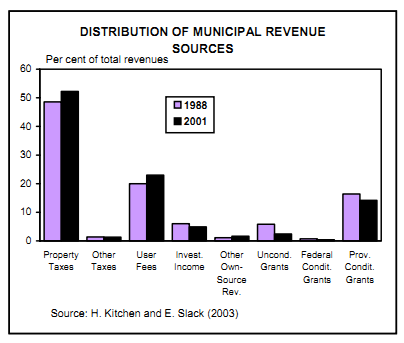

A report released by Harry Kitchen and Enid Slack last year, entitled Special Study: New Finance Options for Municipal Governments estimates increased revenues by municipality in Canada under a number of finance options. These are shown in the accompanying chart. In particular, note that a 1 cent per litre gasoline tax established on the existing provincial base in 2000 would yield about $40 million, $30 million, and $20 million in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver, respectively.24

A standard objection to providing cities with more tax and administrative powers is that they are simply not up to the job. While municipal governments may still lack the expertise and institutional resources that other governments have in certain cases, we see this as a "chicken and the egg" problem. More specifically, as local governments take on added responsibilities, they will soon develop the sophistication to carry out their tasks effectively.

ESTIMATED MUNICIPAL TAX REVENUE FROM A ONE CENT PER LITRE TAX ON FUEL, 2000 Millions of Dollars | ||

City | Yield from the tax | |

Halifax Montreal Ottawa Toronto Winnipeg Regina Calgary Edmonton Vancouver | 6.5 29.6 14.3 38.9 12.2 5.4 17.0 13.0 20.0 | |

Source: Kitchen, Harry and Enid Slack, Canadian Tax Journal | ||

The need to provide cities with a new deal has lost some momentum over the past few budgets in tandem with the urgency to address the infrastructure gap. Still, any lingering chatter has remained focused on revenue sharing, and especially providing cities with a slice of the federal and provincial gasoline tax take. To be sure, any new funds will provide cities with help to meet their most immediate needs. But, the view that revenue sharing is the best way to guard against an increase in the overall tax burden is not well grounded. Regardless of which pocket it comes from, if one level spends more, other levels have to spend less, or the one taxpayer will end up paying more in taxes. And, with grants or revenue sharing, cities remain inextricably linked to changing fiscal fortunes and political considerations of other levels of government.