Municipalities could make better strategic use of debt

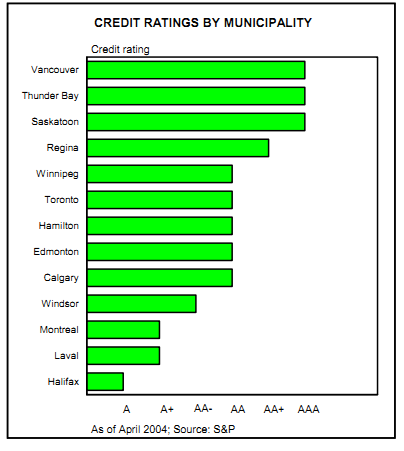

There is a lot to be said for maintaining a low debt burden. For one, a government's total borrowing costs are lower in absolute terms than it would otherwise be if it were heavily indebted - providing more room to fund other priorities. And, second, less indebted governments tend to be more highly rated by bond-rating agencies, and hence have lower per-unit costs of debt financing. Furthermore, flexibility to respond to unanticipated future events is greatly enhanced compared to a jurisdiction that is highly burdened.

At the same time, however, there could be a large opportunity cost associated with not making use of borrowing in certain circumstances. If a government does not have enough internal funds available, a project may be delayed until the proceeds can be raised or be scrapped entirely. On the flip side, debt-financing can provide "just-in-time" financing that will allow construction to go ahead immediately. As importantly, a healthy level of borrowing passes the test of equity, since the benefits - which are normally consumed over a number of decades - are closely matched with the costs. The question then becomes: what constitutes a "healthy" level of debt? Unfortunately, there is no easy answer to that question, as assigning explicit benefits to future generations is difficult. But, this hasn't stopped some researchers from taking a stab at it. Applying the intergenerational-equity principle that debt is warranted to the point that it finances capital that is passed forward, William Scarth of McMaster University has estimated the optimal federal debt-to-GDP ratio set at 25 per cent and a combined-federal provincial ratio at 45 per cent (public-accounts basis), compared to their current levels of about 40 per cent and 65 per cent, respectively.25

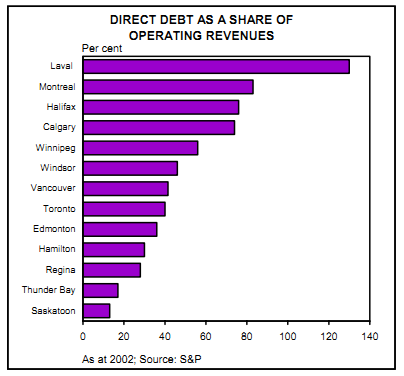

But, while federal and provincial governments have been heavy users of debt for several decades largely to fund past operating deficits, there is a good argument that many municipalities have been overly debt-averse. In several provinces, statutory debt restrictions exist. However, few governments are even remotely close to breaching them. Figures released by Standard & Poor's show that direct debt as a share of operating revenues in most cases stands below 40 per cent, and lower than 15 per cent relative to GDP. As the chart reveals, there are exceptions to the rule - Montreal and Laval have debt burdens above 80 per cent of operating revenues. But, for the most part, municipalities have relied on funding infrastructure primarily through other non-debt sources, including external funds (i.e., federal and provincial grants), direct contributions to capital from operating budgets (i.e. "pay-as-you-go") and monies set aside in special reserves.

MOST INDEBTED U.S. CITIES: Overall Debt Burden and Tax Base: 2002 | |||

| Overall Net Debt (US$M) | Tax Base FY 2002 (US$M) | Overall Debt Burden (%)* |

New York City Chicago Los Angeles Philadelphia Houston | 43,767 12,793 6,574 5,700 4,867 | 409,607 189,362 230,142 39,150 95,539 | 10.7 6.8 2.9 14.6 5.1 |

Washington San Antonio Detroit Phoenix San Diego | 3,356 3,043 2,826 2,469 2,482 | 52,522 39,588 21,952 63,269 92,526 | 6.4 7.7 12.9 3.9 2.7 |

* ratio of debt to tax base; Source: Moody's | |||

Part of the problem preventing the increased use of borrowing by municipalities to finance infrastructure is that many - in particular smaller communities - lack the expertise of their federal and provincial counterparts. Moreover, some may not have bond ratings, or may be rated so poorly that they can't issue bonds or if they did, the resulting costs would be prohibitive. However, some provinces have come up with solutions to this problem. In particular, Ontario and British Columbia have set up centralized provincial authorities to borrow on capital markets at their credit rating, and correspondingly lend the funds out to municipalities at the lower rate.