Benefits, not just costs, should be considered

P3s also face resistance from the belief that they always fail to deliver value to the public sector because the cost of private financing is simply too high. This argument is grounded on two facts. First, the government can borrow money at a cheaper rate than the private sector, as the bonds of the former are backed by tax revenues and so are deemed to be virtually risk free. And, second, in contrast to public-sector provision, the private sector will require a reasonable rate of return on its investment, exacerbating concerns that the financial benefits that accrue to the private sector will be more generous relative to a publicly-funded model or relative to the benefits that the public derives from the delivery of the good itself.

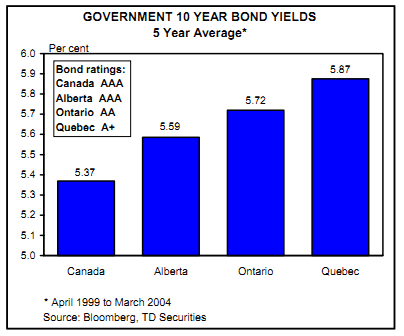

These are valid concerns, but they oversimplify the cost issue. For one, as in the case of measuring the infrastructure gap, there is an opportunity cost involved when governments tie up significant resources to a particular cause, which few analyses take into account. These costs - which include elevated tax rates, debt-loads or an inability of government to take advantage of more beneficial opportunities when they arise - can be significant. And, in some instances, they can be measured with some precision. Excessive borrowing, for example, may lead to a downgrade in the credit rating of a government, which would not only result in higher costs for new debt but for refinancing existing obligations. And, given that Canadian governments are still heavily indebted, despite recent progress in lowering debt burdens, the risks of a downgrade can not be ignored.

In any event, it is not cost, but net benefit, which is the most relevant benchmark in considering which way to go. And, on this count, P3s have the potential to provide significant bang for the buck by leveraging the skills, talent, and deep pockets of the private sector. Although the Canadian experience in P3s is too nascent to provide much evidence on this front, the United Kingdom offers some good proof, where the private sector has a consistent track record for carrying out projects ahead of schedule and avoiding cost over-runs that are common under traditional public procurement. In fact, the National Audit Office (NAO) in the U.K. has revealed that only 24 per cent of P3 projects were delivered late to the public compared to 70 per cent in the public sector. Similarly, cost over-runs occurred in only 22 per cent of the time under P3s compared to 73 per cent in the public sector.28