Too much leakage

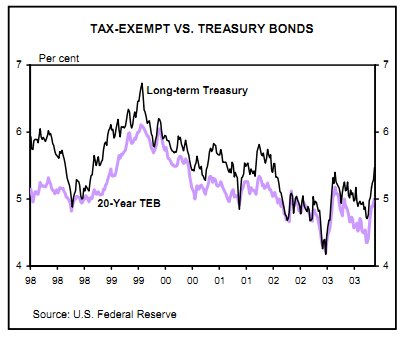

To make matters worse, the U.S. experience indicates that taxpayers are not often willing to pay a premium that is exactly equal to the full amount of available tax savings. This means that the break-even yield of 3.74 per cent calculated in our example would actually have to be higher in order to attract buyers, thereby reducing the cost-advantage of financing a project with TEBs. In fact, it is estimated that only two-thirds of every dollar of tax-subsidy reaches the municipality in the form of reduced costs, with the rest funneling to the bondholder. U.S. financial markets provide stark evidence to this point. In 2003, the average spread between 20-year TEBs and 20-year taxable Treasuries was a slim 30 basis points. But, because TEBs are disproportionately held by income earners in the 25 per cent or higher tax brackets, a spread in the neighborhood of 100 basis point would be more representative of the extraction of the federal tax benefit to the municipality. Therefore, the money saved by state and local authorities in lower payments is considerably less than the cost of the tax break to the federal government. Clearly, it would be more efficient for the federal government to deliver a direct grant to the municipalities for infrastructure projects rather than promote the use of tax-exempt bonds which leak a significant amount of the benefits.