P3 value extends beyond financing

Whole-of-life solution: There are synergies to be gained from combining design, construction and operation, which contribute to a reduction in operating costs and an enhanced level of service.43 The private sector is often more efficient and innovative in undertaking the design, construction, operation and maintenance of an asset if it also shoulders the responsibility of its performance over the whole life cycle. For example, in the case of the Confederation Bridge, the private sector not only assumed all the construction risks related to the design and development of the bridge, but once completed it also assumed operation and maintenance costs for the next 35 years. Of course, any shortcomings in the design or operation would escalate the private firm's costs and bite into their revenues, which are earned via vehicle tolls over this period. What's more, the private sector's obligation does not end after 35 years, because at the end of the contract, the bridge is transferred back to the government for a price of $ 1 in a condition that supports an additional 65-year life. This "whole of life solution" helps assure quality and cost efficiency -further supported by the fact that the Confederation Bridge project has won more than 15 national and international design and construction awards.

KEY FACTORS UNDERPINNING VALUE • Reduced life cycle costs • Better allocation of risk • Faster implementation • Improved service quality • Generation of additional revenue |

Timeliness must also be factored into the value equation of a public-private partnership. The more seasoned P3 market in the UK delivers clear evidence that private firms have greater success at avoiding timetable slippage and the associated costs that are common under traditional public procurement. In 2003, the UK Auditor General evaluated the performance of 37 public-private sector projects and found that only 24 per cent of these were delivered late to the public, of which only 8 per cent were delayed beyond two months. In contrast, the latest statistics on construction projects undertaken exclusively by the public sector indicated that 70 per cent had been delivered late. The gap between private and public performance is not necessarily a reflection of public sector inefficiencies, but rather, of the benefits that the government can extract from the private sector in sharing the risks of the project. First, government payment for the asset usually occurs only after it is up and running, providing a strong incentive for private firms to deliver the project on schedule. Second, many P3 contracts incorporate penalties that accrue to the private consortium in the event that a project is delivered late or does not satisfy predetermined safety and quality standards.

Cost Overruns: The risk of overrun costs also appears to be better managed in the hands of the private sector. Here again the UK Auditor General report provides strong evidence, with only 22 per cent of private sector projects experiencing cost overruns compared to 73 per cent in the public sector. And, in the cases of a private consortium, the price increases were generally small and not due to that consortium charging more for the work than originally specified.44 Importantly, in the P3 cases where overrun costs are not associated with changes to the contract, it is the private sector that absorbs them, not the government.

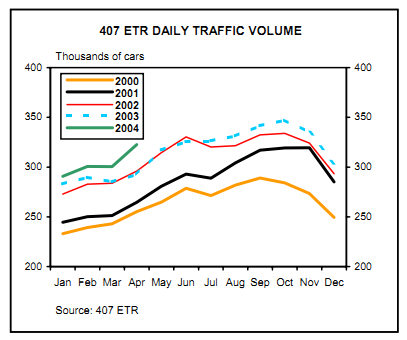

Scale: The scale of a project also enters into the value equation. P3s can provide a means for larger scale projects where fiscal budget constraints may place them out of reach. For instance, the need for highway 407 in Ontario was obvious to the provincial government as a means of reducing congestion on highway 401 - which is reported to be one of the most traveled highway in all of North America - and other 400 series highway links. However, in the early 1990s, the province had limited capability to take on a project of this scale, as it emerged from a recession that had deepened its deficit and debt positions. In all probability, it would have taken decades to develop the new highway under the traditional public model. So, the government enlisted private interests to build, operate and manage the highway. The first 36 km was up and running within four years.45 Today, Ontario boasts a multilane highway that stretches 108 kilometers, benefiting more than 320,000 commuter trips every day during the workweek.46