P3s without borders

Although P3s work well in sectors that generate identifiable income, they are certainly not restricted to these types of infrastructure projects. P3s have tiptoed into areas of education and health care in Canada, but the results have been mixed or still need to be tested against time.

For instance, economic hardship in the province of Nova Scotia in 1997 lent itself to an ambitious and creative program that facilitated public-private partnerships for school construction. By 1998, eight schools were built, 30 were approved and 12 were in the development phase. The schools were turnkey operations, constructed to the province's specification with developers providing desks, blackboards, telephones, computers along with full financing. The lease to the developers extended 20 years, however building use covered school hours only. Importantly the school systems lease payments are only about 85 per cent of the capitalized cost of the building. The remainder of the cost is absorbed by the developer, who earns additional income by leasing the building to other approved entities during non-school hour. The arrangement was set up to incentivize the developer to build cost-effectively in order to reduce financing costs and also to design and build competitive facilities in order to attract the necessary non-school lessees. In addition, since the school system is under no obligation to purchase the building at the end of the lease (though it has the option to do so), it is in the developer's best interest to maintain and upgrade the building in order to maintain marketability.49

On paper this seemed like a good idea, but these P3s ran into a number of roadblocks that eventually grounded the government initiative in 2000. One of the first problems is that there are limitations on alternative off-hour revenue sources due to the very nature of a school. For example, teachers and students tend to personalize classroom space, the chairs for children are too short for adult events, while desks are too low. In the end, the developer was not dealing with an empty, fully functional rentable space. To make matters more difficult, some developers faced public resistance in attempts to crowd in on other revenue sources from vending machines and cafeterias, as school operators were accustomed to using these funds to purchase additional school and student supplies. In the end, it was difficult to find an appropriate level of risk transfer without creating a public tidal wave of hostility towards the endeavor. That is not to say that P3s can't work in education, as the UK boasts over 100 cases. However, this is a relatively new area for Canadian P3 ventures, and it may require some fine tunning in policy objectives. Not to mention that it is always necessary that the public is fully on board with the initiative.

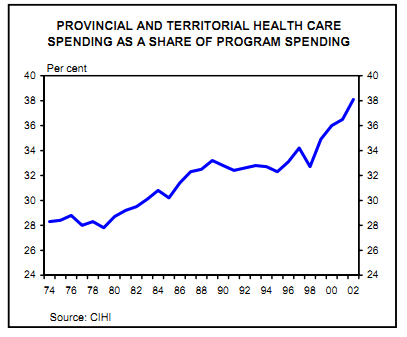

Canada's health care system is finding itself in a similar predicament. Combined health care budgets from the provincial and federal governments already amount to 42 per cent of total operating spending and are expected to trek higher as an aging population intensifies demand for services down the road. Not surprisingly, governments are increasingly willing to consider P3 initiatives for health care facilities. To be perfectly clear, Canada's single public-payer model for health care services is efficient and equitable and should not be compromised. But, it is possible to stick with a single public payer model and still have private sector involvement in the delivery of services, with the government continuing to stringently regulate and impose guidelines to ensure quality.

Let's face it, many hospitals in Canada already contract out a number of non-clinical hospital support services - such as food preparation, catering and cleaning - to the private sector. In fact, a survey conducted by Canadian Healthcare Manager in the summer of 2003 indicated 69 per cent of the hospitals surveyed are already engaged in some form of public-private partnerships. And, of those that were not, more than one-quarter planned to partner with the private sector over the next 12 months. Recently, some provinces have begun to extend the role of public-private partnerships to more far-reaching contracts in recognition of the synergies in bundling services already contracted out to individual private interests. And, there is an argument to be made for governments to focus their resources on the core business of providing healthcare services, rather than on building maintenance.

In 2001, Ontario launched a pilot P3 program with the William Osier Hospital in Brampton. The current hospital facilities were proving to be insufficient in a region that was experiencing annual population growth of 20,000 to 30,000. As a result, plans were put in place to support the construction of a fourth hospital. With provincial government resources already spread thin, the government enlisted private interests to provide services for facility design, construction, capital financing, building maintenance, materials management, housekeeping, laundry, food services, parking and security operations. In effect, the P3 contract represented a DBFO venture. It is estimated that the hospital will take less than six years to complete from start (planning process) to finish (availability of services), less than half the time estimated under a traditional government model. And, the risk of cost overruns is transferred to the private sector. In many ways, this P3 contract is built on many of the lessons learned from the UK private finance initiative which attempts to encompass full business case analysis for project development in order to provide a good sense of savings on the operating front from capital investment. Planners in the William Osier project also looked at historical data and created value for money benchmarks against which performance could be measured. These benchmarks were then included in the construction, life cycle and operating costs over a 25-year period.

This P3 arrangement allows the government to deliver needed state-of-the-art facilities in a timely and efficient manner to the public. In addition, the contract maintains strict government control over clinical services and regulation over the public assets. Perhaps the biggest challenge for the government will be to overcome public concerns that services and costs will be compromised under a private consortium. As it stands, political wrangling has delayed construction on this project, though the hospital remains committed to the 2006 completion deadline. Although performance standards are incorporated in the P3 contract, only the test of time will determine if the government has effectively defined clear boundaries and set guidelines towards a measurable output performance in order to critically evaluate the lease over its life term. And, importantly, whether the benefits derived through a private consortium exceed the extra costs imposed on the government for its delivery.