Introducing empirical impact evaluation

9.5 Fundamentally, evaluating policy impact involves:

• determining whether something has happened (outcome); and

• determining whether the policy was responsible (attribution).

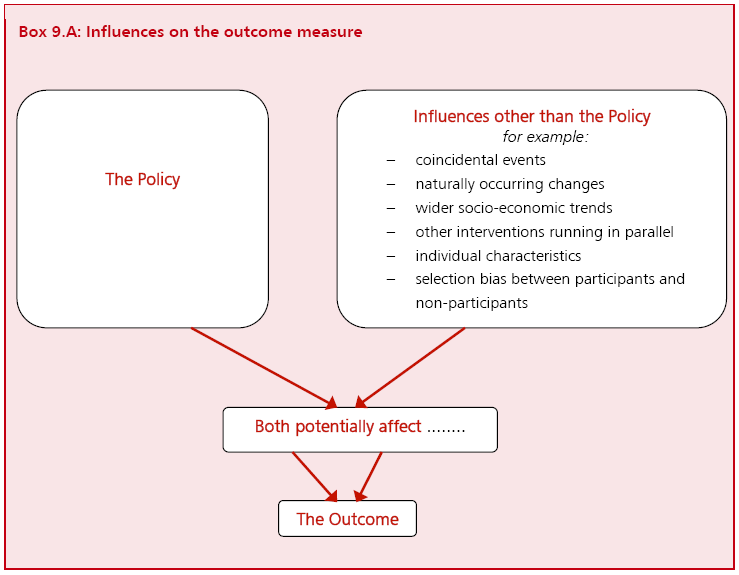

9.6 The first of these points lies in the realm of descriptive statistics and is an important first step which has its own challenges. But it is the second point - establishing attribution - that is the defining feature of impact evaluation. This second stage is frequently the more challenging of the two, and can restrict the types of policies for which impact evaluation is feasible. The main problem is that other causes outside of the policy might have affected the outcome, as illustrated in the influence diagram in Box 9.A. The challenge of impact evaluation is to separate the effects of the policy from the other influences.

Box 9. A: Influences on the outcome measure

9.7 A key concept in impact evaluation is the counterfactual - what would have occurred had the policy not taken place. By definition it cannot be observed directly, because the policy did take place. Impact evaluation seeks to obtain a good estimate of the counterfactual, usually by reference to situations which were not exposed to the policy.

9.8 In broad terms, a robust impact evaluation requires:

• a means of estimating the counterfactual;

• data of adequate quality and quantity to support the estimation procedure; and

• that the level of "noise" in the outcome is sufficiently low to detect what might be a reasonably expected policy effect.

9.9 In practice, some or all of these requirements may be outside the control of the evaluator. To meet them often requires putting measures in place before the policy starts. For example, this could include manipulating the allocation of interventions (discussed below and in Chapter 3), and setting up appropriate data collection both to act as a baseline and during the policy intervention.

9.10 The remainder of this chapter is largely concerned with research designs, typically involving a comparison group as a means of estimating the counterfactual. But in some very simple cases, the mechanism may be sufficiently transparent that the impact can be observed directly, or through process evaluation, without the need to control for confounding factors. For example, with a project to supply water to a village in a developing country, any observed decreases in the average time household members spend collecting water might be attributed to the project without the need for a comparison group2. As suggested in Chapter 2, the more "distant" are the factors or links in the logic model between which it is desired to estimate the impact, the more likely it is that there will be a range of possible explanations for any change in the outcome of interest, and the more important it will be to estimate a counterfactual. More often in public policy, the causal link between policy and outcome is an indirect one, and a counterfactual estimate is required.

____________________________________________________________________

2 Some Reflections on Current Debates in Impact Evaluation, International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie): Working Paper 1, White, 2009, New Delhi