Building a program does not merely require identifying projects but also cultivating the broader environment in which projects will progress

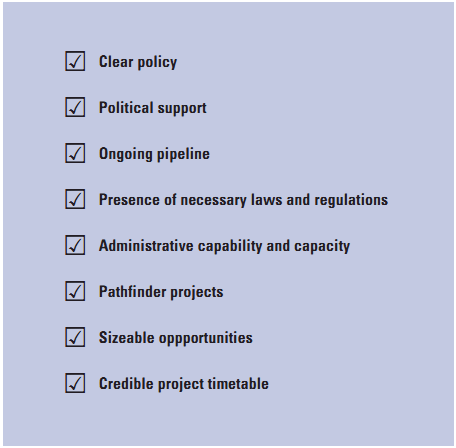

Some of the features that are needed to support a program are listed in Figure 1. The absence of any of these elements will jeopardize the successful outcome of the project.

One of the reasons these features of infrastructure projects are important is that projects typically require a long lead time, from identifying the opportunity to closing the contract. Even in countries with an established PPP program supported by standard contracts, an established procurement framework, and cross-party political support, it takes on average just under three years to tender and reach financial close on a PPP proj-ect.2 The investment payback time is even longer. If there is a construction period, then the debt repayment might not start for three or four years after the contract has been signed; the time for equity payback may be many years after that.

During this project procurement period, private financiers are likely to have invested significant time and resources to develop the opportunity, often in a competitive bidding process. They will recover these on contract close only if they win and the project proceeds. It can be difficult to put a number on these costs, but, to provide some context, a private-sector consortium is claiming compensation of about UK£ 27.8 million following the cancellation of a PPP hospital project some 20 months after the consortium had been appointed the preferred bidder.3

We will discuss in greater detail some of the key features of a project programme that can help overcome some of these initial frictions.

The procurement policy: Political support with a clear investment rationale is crucial

If political support is undefined and procurement policy lacks clarity then investors will not even want to establish a presence in the market. In many respects, this has happened in the United States with its P3 program. In the past few years, a number of international corporate investors and contractors established teams in the United States in the expectation of a substantial program of PPP projects, but there have been fewer opportunities than anticipated. Those investor teams have been repatriated or downsized and are not even certain that they would return if the sector develops.

| Case in Point 1: The British Columbia PPP program |

| Partnerships BC is a dedicated agency created in 2002 to evaluate, structure, and implement public-private partnership (PPP) projects in the Province of British Columbia, and to act as a center of procurement expertise. It was established because of a serious infrastructure gap in health, advanced education, and transportation. The agency is wholly owned by the Province of British Columbia and reports to the Minister of Finance, its only shareholder. Current funding for Partnerships BC is C$6-8 billion. The core business of Partnerships BC is to: • provide specialized services for government and its agencies, ranging from advice and project leadership/management to identifying opportunities for maximizing the value of public capital assets and developing PPPs; • foster a business and policy environment for successful PPPs and related activities by offering a centralized source of knowledge, understanding, expertise, and practical experience in these areas. It does this at all stages of a project from the initial feasibility analysis and preparation of business cases through to the procurement process and to project implementation; and • manage an efficient and leading-edge organization that meets or exceeds performance expectations. Since 2002, Partnerships BC has been involved with approximately 30 projects with a capital value approaching C$10 billion, including Abbotsfield Regional Hospital & Cancer Centre (C$355 million), Sea-to-Sky Highway Improvement Project (C$600 million), and the William R. Bennett Bridge (C$144 million). Each completed PPP project in British Columbia has achieved value for money for British Columbia taxpayers, including (1) quantitative factors such as life-cycle savings and (2) qualitative factors such as appropriate risk transfer and performance-based contracts that ensure that high-quality infrastructure and services are provided by the private-sector partners. |

|

|

| Case in Point 2: The SCUT roads program, Portugal |

| In 1996, the Portuguese government set up a program to procure seven shadow toll road concessions to upgrade or build approximately 900 kilometers of roads at an estimated capital cost of €5 billion. The projects were commonly referred to as SCUT projects, reflecting the acronym for Sem Custos par os Utilizadores (translated as "No Cost to the Users"). The government wanted to achieve rapid growth of both its internal road network and transport links with Spain. However, given national constraints on its ability to deliver and finance such an ambitious undertaking, the government needed to structure a program that would attract international bidders and financiers. Although the early programs threw up some challenging procurement issues, such as those relating to land expropriation and environmental permits, within three years the first two concessions had been awarded and all seven were in place by September 2002. The projects were primarily financed by a combination of project finance banks, both local and international, and the European Investment Bank. In 2007, all of the concessions were fully operational. By any measure this was quite an achievement. The success of the program has been tarnished by the budgetary burden that the shadow toll regime has created for the government. Shadow tolls are actual payments made by the government to private-sector operators of a road based on factors such as the number of vehicles using the road in a given period. The shadow toll subsequently provides the finance for these privately funded road schemes under a design, build, finance, and operate (DBFO) program. In 2007 it was announced that the concessions would be converted to real tolls, but the terms of the conversion are still subject to negotiation. |

|

|

Figure 1: Key factors in a successful infrastructure project programme

Another factor that helps to indicate the presence of political and policy support is the ability to demonstrate that the program is fully integrated with and reflects a country's infrastructure needs and has mainstream support. Recently the Australian government has pioneered a move to establish independent bodies, such as Infrastructure Australia, charged with auditing the nation's existing infrastructure and putting in place long-term planning and prioritization of infrastructure investment. The Australian government is building its procurement programs around this work (see Case in Point 3: Australia's Future Fund and Infrastructure Australia).

Ongoing pipelines of opportunities are more likely to attract bidders than ad hoc procurement

The concern of investors is primarily whether the opportunity is a one-off or there is the possibility of repeat opportunities. This information will help them assess the size of the potential market and whether the opportunity is one that they can build a team and/or business around. Having a program not only encourages more investors to enter into the market but should also create a more competitive environment. This competition should in turn generate better overall value for money because future deals should benefit from a more streamlined and quicker process with experienced practitioners on both sides of the transaction.

For investors, having a pipeline of bidding opportunities means they can hope to have a higher probability of success, which in turn allows them to consider the cost of bidding across this portfolio of bids rather than on a project-by-project basis.

The necessary laws and regulations must be in place before transactions take place

Developing a procurement process that does not fit with the existing relevant laws and regulations is highly costly and time-consuming. This is also one of the areas that will be a main deterrent for private investors. Sometimes the insufficiency of the existing laws is not known or understood until the parties are in the heat of a transaction. To mitigate this risk, selecting a small number of pathfinder projects that can be used to test the approach planned for the main program can provide substantial benefits, as it will bring to the fore circumstances where the existing laws and regulations are inadequate.

| "A program of opportunities that creates a steady

|

Administrative support needed for a successful program should not be underestimated

There are significant advantages in supporting a clear program with "standard" procurement routes, where various factors, such as the procurement timetable, contract and regulatory regimes, and payment mechanisms, are familiar. Investing time and effort in advancing these routes helps. This requires substantial administrative support not only to put the processes in place but also to coordinate and monitor their implementation across procuring bodies and over time (see Case in Point 1: The British Columbia PPP Program).

Pathfinder projects preempt problems and demonstrate success

There is strong evidence that, in developing a new sector, if the public authority can articulate a program of prioritized opportunities with pathfinder projects to test and refine the proposition, projects are more likely to attract greater commercial interest and competitiveness among private finance solutions. One example of a successful program that used a pathfinder approach is India's PPP program. The highways portion of that program alone, launched in summer July 2009, is probably the biggest

| Case in Point 3: Australia's Future Fund and Infrastructure Australia | ||

| Future Fund | ||

| The Future Fund approach was first established by the Australian government in 2006 to assist future Australian governments in meeting the cost of public-sector superannuation liabilities by delivering investment returns on contributions to the Fund. Subsequently, three "sister" funds were established in 2008 to focus on certain kinds of infrastructure. These included the Building Australia Fund, the Education Investment Fund, and the Health & Hospitals Fund. These three funds are referred to as the Nation-Building Funds. | ||

| The value of these funds on 31 December 2009 was: | ||

| Fund | $A billions |

|

| Future Fund | 66.2 |

|

| Education Investment Fund | 10.1 |

|

| Health & Hospitals Fund | 4.9 |

|

| Investment responsibility of the Future Fund lies with a board of guardians, while administrative and operational support is offered by a management agency. The Future Fund has received contributions from governmessnt budget surpluses as well as proceeds from the sale of the government's holdings of Telstra and the transfer of the 2 billion remaining Telstra shares. Funds will be withdrawn only after 2020. The exceptions will be to meet operating costs or if the balance exceeds the target asset level. | ||

| The Building Australia Fund is funded from government budget surpluses in 2007-08 and 2008-09. It is focused on building critical economic infrastructure including roads, rail, port facilities, and broadband facilities. Expenditure will be guided by Infrastructure Australia's infrastructure priority list. | ||

| Infrastructure Australia | ||

| Infrastructure Australia was established by the Australian government in April 2008 to develop a plan for Australia's future infrastructure needs and to facilitate its implementation. Infrastructure Australia's role is to advise the Australian government, state governments, investors, and infrastructure owners concerning nationally significant infrastructure priorities, desirable policy and regulatory reforms, options to address impediments facing national infrastructure, the needs of users, and possible financing mechanisms. It accomplishes this by: | ||

| 1. conducting audits on all aspects of nationally significant infrastructure, in particular water, transport, communications, and energy; | ||

| 2. drawing up an infrastructure priority list involving billions of dollars of planned projects; and | ||

| 3. advising government, investors, and infrastructure developers on regulatory reform and procurement guidelines aimed at ensuring efficient use of infrastructure networks and speeding up project delivery. | ||

| Key stakeholders include Australia's states, territories, and local governments as well as the private sector. | ||

| Achievements | ||

| • Thirty-six programs had been started and/or completed by June 2009. These include the North-South Bypass Tunnel (Queensland government), the Alternative Waste Technology Facility (New South Wales government), and the Defense Headquarters Joint Command Facility | ||

| • the completion of the national infrastructure audit; | ||

| • the development of an infrastructure priority list; and | ||

| • the development of best practice guidelines of public-private partnerships. | ||

PPP program in the world: it has an estimated investment of US$70 billion over the next three years, with private-sector participation expected to be about US$40 billion, of which US$10 billion is expected to come from foreign investors. The public procurers intend to use the experience of the past five years to make the procurement investor friendly (see Case in Point 4: India's PPP program).

Another example is found in the Chilean roads program. The success of the original program is due at least in part to its innovative structure, which allowed the government to flex the concession period so that investors could achieve target return. A number of these projects are now on the secondary market (see Chapter 1.3 Case in Point 2: Chilean private-public partnership roads program).

| Case in Point 4: Public-Private Partnerships: India |

| Overview |

| Public-private partnerships (PPPs) in India were established to leverage public capital to attract private capital while also benefiting from private-sector expertise, operational efficiencies, and cost-reducing technologies. At the central government level, these partnerships are coordinated by the Government of India (GoI) through the Ministry of Finance (Department of Economic Affairs). The GoI has also announced various policy initiatives in order to foster an enabling environment for PPPs. These include fiscal incentives, a streamlined approval process, and a stable policy environment |

| As of 2007, there were more than 300 PPP contracts signed in the country. India is expected to have an investment requirement of US$500 billion over the next five years, with US$150 billion expected through PPP projects. It is the biggest PPP program in the world. |

| Key stakeholders include the Ministry of Finance (GoI), sectoral ministries (such as Roads, Aviation, etc.), private institutions, and Indian states. The sectors handled include highways, railways, ports, airports, and power. Recently, the GoI has started experimenting with PPPs in social sectors such as health, education, and housing. |

| Funding |

| The India Infrastructure Finance Company Limited (IIFCL) has sanctioned US$4.6 billion (as of October 21, 2009) in financial assistance to 95 projects across 5 sectors. The IIFCL lends up to 20 percent of project costs. Other institutions that have provided financial assistance include the Infrastructure Development Finance Company (IDFC), ICICI Bank, the State Bank of India, Punjab National Bank, Canara Bank, and Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services Limited. Multilateral agencies are also active in the infrastructure financing, and one of them-the Asian Development Bank (ADB)-has been allowed to raise rupee bonds and carry out currency swaps to provide long-term debt. Dedicated infrastructure funds are being encouraged in order to provide equity. An example of this includes the India Infrastructure Finance Initiative. |

| From 1995 to 2007, senior debt accounted for 68 percent of project financing, on average. The rest took the form of equity (25 percent), subordinated debt (3 percent), and government grants (4 percent)-which are typically viability grants provided during construction to PPPs deemed economically desirable but not financially viable. Typical concession terms encourage the use of debt over equity. |

| The scale of this investment is illustrated by the State Bank of India coming out as the No. 1 Global Initial Mandated Lead Arranger in the 2009 Project Finance International league tables-they arranged lending for 37 deals with total lending of US$19.9 billion, representing 14.3 percent of total lending nationwide in the year. |

| Successes |

| Some of the achievements to date include the modernization of the Mumbai and Delhi International Airports, improvement of various port facilities, greenfield private ports, several national highways, and the commercial utilization of surplus land. The roads building program aims to build 7,000 kilometers each year for the next five years. This translates to approximately 20 kilometers per day; currently, approximately 10 kilometers of roads are being built each day, more than double the rate of a year ago. |

|

|