The capital structure reflects not only the risks and opportunities in a market but also external factors such as tax policy

The capital structure is the relationship between debt (and classes of debt) and equity, often referred to as leverage or gearing.

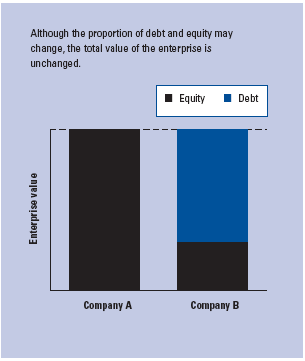

It was Modigliani and Miller who described the proposition that a firm cannot change the total value of its securities just by splitting its cash flows into different streams;2 although the split does affect the returns each investor class may expect to receive, the total value of the enterprise is unchanged. This concept is very simply illustrated in Figure 2. The complication is that the proposition assumes that decisions are being made in perfect capital markets.

Further works, such as that by Brealey and Myers,3 have highlighted the imperfections that can affect capital structure. Examples of these limitations include taxes, the cost of financial distress and bankruptcy, and the cost of making and enforcing complicated debt contracts.

The impact of taxation policy is of particular importance and needs to be considered carefully for each tax regime under which an investment is being made. For example, under some tax regimes, interest expense is tax deductible and thus reduces the amount of tax paid at the company level. This can encourage more debt and thus higher leverage, without changing any other factors relating to the enterprise. However, for the purposes of this Report, we do not consider or comment on the specific impact of taxation policy.

The capital structure or leverage can affect the overall enterprise value and the risk-reward proposition of the different types of cash flow. Some examples are:

• The level of return that each investor class expects to receive will reflect the level of risk that the investors in that class are prepared to take, partly in relation to other investors in the same transaction and partly in relation to the risk and rewards of alternative or competing investment options.

Figure 2: Effect of capital structure on overall value

• A highly leveraged enterprise may be regarded as carrying higher risk than one with less debt. This is because debt costs are not discretionary, and failure to meet those costs may ultimately lead to a loan default, which in turn could lead to the demise of the enterprise. However, equity payments or dividends are discretionary. Clearly the ability to pay debt costs is closely linked to having the revenue to make those payments (alongside controlling other operating costs).

However, we cannot say that "high leverage" is bad and "low leverage" is good without first understanding the dynamics of the particular enterprise or sector we are reviewing, taking into account both the nature and predictability of revenue and costs. Indeed, the question as to whether leverage is random across industries must be asked. Figure 3 shows some leverage amounts for a variety of enterprise sectors and some infrastructure-specific ventures. That companies operating within the same industry group have similar leverage should be expected, as they will be operating under similar conditions and risks-for example, predictability of revenues, business cycles, capital investment requirements, and opportunities for growth.

In certain sectors, such as media, leverage is typically below 40 percent but in the public-private partnership (PPP) sector it may be more than 90 percent. The main reasons for this are the difference in the risk profiles between the two sectors, their respective equity investors' appetite for risk, and their ability to repay debt. The high leverage of a typical PPP transaction reflects the perceived low risk of long-term contracted revenues, often with a sovereign counterparty, fixed costs, and detailed contractual arrangements.

Figure 3 is also a snapshot in time, 4 as the analysis is primarily based on information for the period between 2007 and 2009, inclusive. What is interesting is how leverage can change and why. For example, the current shortage of capital is lowering the debt amount and increasing the equity requirement across many industries, but this is happening without regard to the actual performance of an individual asset or market sector.