2 A Bare-Boned Model

We consider the following public procurement context: A government (thereafter the principal sometimes refereed to as G) relies on a private firm or consortium (the agent F) to provide a public service for society. Examples of such delegation include of course transportation, water production and sanitation, waste disposal, etc. In such settings, providing the service can only be done if an infrastructure of a sufficiently good quality has been first designed and built. Clearly, this delegation of services towards the private sector must be modeled as a multi-task problem.12 The main feature of a PPP can then be viewed as the bundling of various phases of contracting. Typically the design (D), building (B), finance (F) and operation (O) of the project (this is the so-called "DBFO model") are contracted out to a consortium of private firms. This consortium is made of at least a construction company and a facility-management company and it is responsible for all aspects of service.13

By exerting a quality-improving effort (or, in an alternative interpretation of our model that will be sometimes used thereafter, making some investment in the quality of the infrastructure), the agent improves the quality of public service. The corresponding social benefit is worth

B = b0 + ba

where the marginal benefit of the agent's effort is positive (b > 0) and b0 ≥ 0 denotes some base level for the benefits of the service that is obtained even without any effort. We also assume that the social benefit is hardly verifiable.

Providing the service costs to the firm an amount

C = θ0 - e - δa + ε.

The random variable ε is normally distributed with variance σ2 and zero mean. It captures any operational risk that the firm may incur when managing the asset. θ0 is the innate cost of the service (linked to the technology used) and e is the agent's effort in cost-reducing activities.

Two alternative scenarios will be particularly analyzed in the sequel. The case δ > 0 corresponds to a positive externality where improving the quality of the infrastructure also reduces the operational costs. For example, the design of a prison with better sightlines for staff that improve security (i.e., social benefit) may yield the positive externality that the required number of security guards is reduced. The case δ < 0 corresponds to a negative externality where improving the quality of infrastructure increases operational costs. For example, an innovative design of a hospital, using recently-developed materials, may lead to improved lighting and air quality, and therefore better clinical outcomes, but may also increase maintenance costs.

Quality-enhancing and operating efforts have monetary costs for the agent. For simplicity, these costs are respectively given by the quadratic disutility functions ![]() and

and  There are no (dis-)economies of scope between efforts.

There are no (dis-)economies of scope between efforts.

Delegation of services to the private sector takes place in a moral hazard environment so that both a and e are nonverifiable. Only the operating cost C is observable and can be used ex ante at the time G and F contract together. Consistently with many examples of PPP projects, the social value of the project is hardly contractible and no related statistics even a rough one can be used to condition payments on realized social value. Moreover, both the government and the firm are ignorant of the realization of cost uncertainty.14

The risk-neutral government G is supposed to maximize an expected social welfare function, defined as the social benefit of the service net of its costs and of the payment made to F.15 The firm F also maximizes his expected utility and is risk-averse with constant degree of risk-aversion r > 0. This captures the fact that a PPP project might represent a large share of this firm's activities so that the firm's activities can hardly be viewed as being fully diversified.

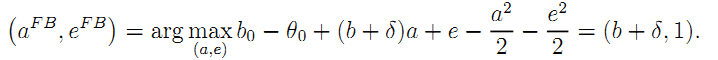

• Benchmark: For future references, it is worth describing the first-best levels of effort aFB and eFB that would be achieved had those efforts been observable and contractible. At the first-best, the risk-averse agent is of course fully insured by the risk-neutral government through a cost-plus contract. Given that the public authority can run a competitive auction to attract potential service providers, we assume that it has all bargaining power ex ante and chooses a fee for the service provider that makes him just indifferent between

producing the service or getting his outside option normalized at zero. Moreover, that contract also forces the firm to choose the first-best efforts defined as:

|

| (1) |

The first-best quality-enhancing effort aFB trades off the marginal social value of that effort, including its impact on operating costs (δ) and on the social value of the service (b), with its marginal cost (a). The operating cost-reducing effort eFB trades off the marginal benefit of lowering those operating costs (1) with its marginal monetary disutility (e).

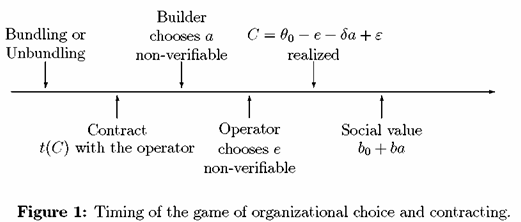

• Timing: The contracting game unfolds as depicted by means of the following time line.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

12 Holmström and Milgrom (1991).

13 Variations of the DBFO contract include Design-Build-Operate (DBO), Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT), Build-Own-Operate-Transfer (BOOT), Build-Lease-Operate-Transfer (BLOT), etc...

14 Focusing on such moral hazard environment fits well with the observation made by Bajari and Tadelis (2001) that, in many procurement contexts, the buyer and the seller face the same uncertainty on costs and demand conditions.

15 The assumption of risk-neutrality for the government gives a simple benchmark: In the absence of moral hazard, optimal risk allocation requires that the public sector bears all risk. This assumption may be questioned in the case of a small local government whose PPP project under scrutiny represents a significant share of the overall budget. In the case of a large country's government, the existing deadweight loss in the cost of taxation may as well introduce a behavior towards risk if the PPP project were to represent a large share of the budget (Barro (1990)). Lewis and Sappington (1995) and Martimort and Sand-Zantman (2007) analyze the consequences of having risk-averse local governments.