3.1 Pure Agency Considerations: Bundling Dominates

Unbundling: Under traditional contracting, G approaches first a builder and then a separate operator. The operator receives a cost-reimbursement rule t(C) net of its cost. Given our CARA-normal distribution environment, we may follow Holmström and Milgrom (1991) and restrict the analysis to the case of linear rules of the form t(C) = α-βC. The case β = 0 corresponds to a cost-plus contract with no incentives in cost reduction, whereas β = 1 holds for a fixed-price.

To simplify presentation, we rule out the possibility that the builder obtains an incentive payment that would also depend on the realized cost C. Instead, the builder receives a fixed payment. This contractual limitations may be justified when G has a limited ability to commit to future rewards for the builder and cannot delay payment for the delivery of the infrastructure. There is also the possibility of a collusion between G and the operator to exaggerate the contribution of the operator to cost-reducing activities and underestimate that of the builder.16

Since he receives only a fixed payment that cannot reward him for the quality enhancing effort he may put into the design of the project, the builder does not exert any effort:

| (2) |

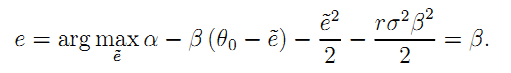

Turning now to the operator who is willing to maximize the certainty equivalent of his expected utility given the builder's own effort, his incentives constraint can be written as:

| (3) |

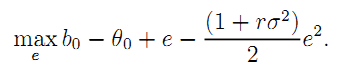

An increase in the power of the incentive scheme β raises cost-reducing effort, but as more operational risk is then transferred to F the risk premium  increases too. Assuming that G has all the bargaining power ex ante with both the builder and the operator, he can extract all their rent and just leave them indifferent between providing the service and getting their outside opportunities normalized at zero. In particular, the fee α is just set to cover the risk-premium that must be paid to have the risk-averse operator bearing some operational risk as requested for incentive reasons. Finally, G just maximizes social welfare taking into account the incentive constraints (2) and (3) and the total benefit and cost of effort, including the risk-premium. This yields the following expression of G's problem:

increases too. Assuming that G has all the bargaining power ex ante with both the builder and the operator, he can extract all their rent and just leave them indifferent between providing the service and getting their outside opportunities normalized at zero. In particular, the fee α is just set to cover the risk-premium that must be paid to have the risk-averse operator bearing some operational risk as requested for incentive reasons. Finally, G just maximizes social welfare taking into account the incentive constraints (2) and (3) and the total benefit and cost of effort, including the risk-premium. This yields the following expression of G's problem:

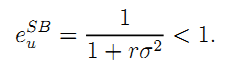

Immediate optimization gives the second-best value of the operating effort as:

| (4) |

Because providing incentives requires the agent to bear more risk and this is socially costly, the second-best effort is less than its first-best level. As it is standard with this linear-CARA model, an increase in operational risk (making σ2 larger) also means that the trade-off between insurance and incentives is tilted towards low powered incentives.17

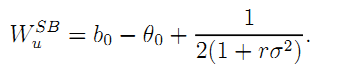

For further references, note that social welfare under unbundling can be written as:

| (5) |

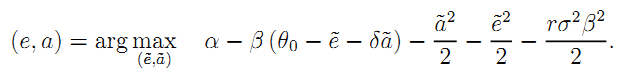

Bundling: With this organizational form, both the building and the operational phases are in the hands of a consortium. The consortium's expected payoff is maximized when the effort levels are jointly chosen to solve:

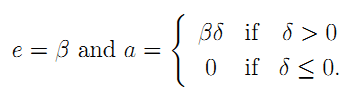

Taking into account the additional non-negativity constraint a ≥ 0, we obtain the following incentive constraints:

| (6) |

Let us analyze the two cases in turn depending on the sign of the externality.

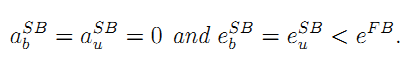

• Negative Externality: When δ ≤ 0, the consortium never chooses to perform a qualityenhancing effort because it receives no direct reward for doing so and it increases its own operating cost. This replicates exactly the same solution as in the case of unbundling.

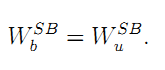

Result 1 With a negative externality (δ ≤ 0), bundling and unbundling yields the same welfare.

There is no infrastructure quality-enhancing effort and a less than optimal cost-reducing effort.

• Positive externality When δ > 0, a consortium internalizes somewhat the impact of building a high quality infrastructure because it reduces also its operating costs. Moving towards a fixed-price contract also raises incentives on infrastructure quality-enhancing; an objective which cannot be directly achieved by the public authority since that quality is hardly contractible.

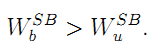

Result 2 With a positive externality (δ > 0), bundling strictly dominates unbundling

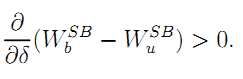

The welfare gain from bundling increases with the magnitude of the externality δ.

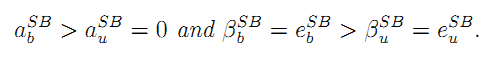

There is a positive infrastructure quality-enhancing effort and an increase in cost-reducing effort. PPP projects are associated with higher powered incentives and more operational risk being transferred to the private sector:

When the externality is positive, bundling induces the agent to internalize the effect of his quality-enhancing investment a on the fraction of cost that he bears at the operational stage. This unambiguously raises welfare, and the stronger the positive externality, the greater the benefit of bundling.

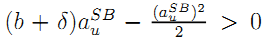

To see why, consider the following thought experiment: Take the incentive scheme offered to the operator under unbundling, and suppose it is now given to the consortium. The incremental welfare gain from doing so is  since now the consortium exerts a quality-enhancing effort

since now the consortium exerts a quality-enhancing effort

Bundling shifts more risk to F and brings the additional benefit of increasing its incentives to invest in asset quality. Moving from traditional procurement to PPP changes cost reimbursement rules. Bundling and fixedprice contracts go hands in hands under PPP whereas unbundling and cost-plus contracts are more likely under traditional procurement. This is in lines with existing evidence that PPP projects are characterized by more risk transfer and thus greater risk-premia than traditional procurement.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

16 We briefly discuss how the results can be extended when this assumption is relaxed in Section 3.2 below.

17 So far, our analysis has assumed away any cost of public funds. Suppose that any transfers from and payments to the government are weighted by a factor 1 + λ where λ is the positive cost of public funds. Then, the objective function is essentially the same as above if the social benefit of the project is deflated by

the same very factor so that it becomes  As a result, since eUSB given by (4) does not depend on the social benefit of the project, the power of incentives under unbundling remains unchanged as the cost of public funds becomes positive. Without uncovering the analysis below, the benefits of bundling tasks will be de facto reduced but still positive. A second by-product of this discussion is that the issue of bundling or not tasks is independent of whether public funds are costly or not.

As a result, since eUSB given by (4) does not depend on the social benefit of the project, the power of incentives under unbundling remains unchanged as the cost of public funds becomes positive. Without uncovering the analysis below, the benefits of bundling tasks will be de facto reduced but still positive. A second by-product of this discussion is that the issue of bundling or not tasks is independent of whether public funds are costly or not.