4.2 Private Finance Initiative

So far we have implicitly focused on conventional PPPs, under which the public sector pays the private sector party for the service that it will provide using the infrastructure. Providers of PPP hospitals, schools and prisons receive their funding in this manner. PPP arrangements however are often characterized by the private sector financing a substantial part, or all of, the project (the "F" in the DBFO model). With financially free-standing projects, the private provider then recoups its initial investment through charges to final users. Here, the public sector involvement is limited to facilitating the project and the PPP is very similar to a concession contract. In this section we briefly study the case of financially free standing projects.

Consistently with the PFI practices, we consider a setting where there are no direct subsidies from the government to the firm and all revenues are left to the firm over the duration of the contract, i.e., α = 0 and β = 1. The firm must cover its initial investment I from the revenues it withdraws from charging user fees over the length T of the contract. After date T, the PPP goes back under public ownership and the access toll is set at zero.

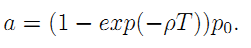

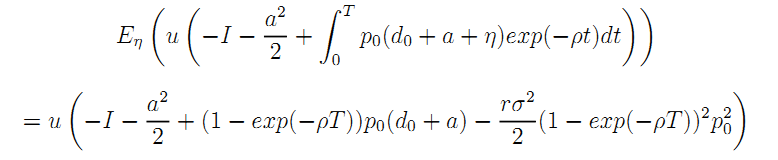

To complete our modeling, assume that the shocks on the level of demand are drawn once for all whereas the cost of effort is sunk and borne once for all beforehand. With these assumptions in mind, intertemporal income smoothing for the firm leads to rewrite the firm's discounted stream of certainty-equivalent payoffs when choosing effort a and making the investment I as:

where ρ is the interest rate in the economy.

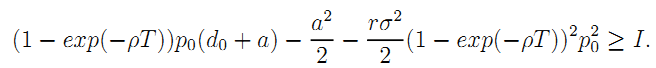

This immediately leads to the following moral hazard constraint:

| (14) |

Clearly, the longer the duration of the contract T, the greater the firm's effort since its benefits accrues over a longer period. Note that the term 1 - exp(-ρT) plays the same role as β in formula (13) above. Indeed, instead of directly sharing the revenue with the firm in each period, the government let the firm enjoy all revenue but for a finite duration.

Also, undertaking the investment is optimal when:

| (15) |

This condition plays the role of a break-even constraint in standard Ramsey analysis when the government cannot use lump-sum payment to finance investment directly. Accordingly, we will now on consider that G is a social welfare maximizer giving equal weight to consumers and the firm in his objective function.

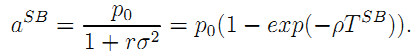

Suppose first that the investment constraint (15) is slack. The second-best effort level is then easily obtained as:

| (16) |

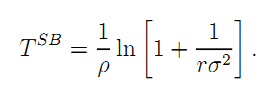

From which, we derive the optimal unconstrained length of the franchise as:

| (17) |

More demand risk and a greater degree of risk-aversion both call for reducing the incentive power and for more insurance which is obtained by reducing the length of the contract.

However, with financially free-standing projects the length of the contract must be chosen so as to guarantee that the stream of expected revenues coming from user charges is sufficient to cover the firm's investment as well as the risk-premium.

Suppose that TSB is such that (15) does not hold. The length of the contract has to be modified to ensure that the firm breaks even. We get:

Result 8 Assume that the investment constraint is binding. Franchise lengths are shorter in more uncertain environments (σ2 greater), when consumers' willingness to pay is greater (p0 greater), when investment is lower (I lower).

Literature: Our framework is related to Engel, Fischer and Galetovic (2001) who study optimal contract length in concession contracts, but in their paper there is no moral hazard. Engel, Fischer and Galetovic (2006) study the rationale for private finance in PPPs.24 They showed that private finance cannot be a means to save on distortionary taxation. Any additional $1 invested by the contractor saves society distortionary taxes but the concessionaire must be compensated for the additional investment through a longer contract term and this costs society future distortionary taxes equal to the initial tax saving. Further, when demand risk is substantial, the optimal contract is characterized by a minimum revenue guarantee and a cap on the firm's revenues.

Applications: Our results suggest that when demand is affected by the contractor's effort, transferring demand risk to the contractor helps incentives. In practice, with financially free-standing PPP projects, the payment mechanism is based on user charges and demand revenue risk lies with the contractor who is then residual claimant for demand changes. With conventional PPP projects, such as hospitals, schools and prisons, the contractor's effort has little impact on demand levels as government policies determine most of demand changes. The payment mechanism is then based on usage with the government bearing demand risk. In our model, it is immediate that if D is independent of a then it is suboptimal to transfer demand risk to the contractor.

The private finance aspect of PPPs has allowed the public sector to finance the construction of infrastructure "off the balance sheet" and to accelerate delivery of projects (see IPPR, 2001). The accounting treatment of this stream of payments can vary and it can often make the government budget look healthier than what it is, thereby under-valuing the cost of PPP financed infrastructure. This not only biases decisions in favor of PPPs as opposed to more traditional procurement arrangements but it can make PPPs a means to unduly transfer costs from current to future generations.25

There is no economic justification for PPPs being promoted for allowing investment off the balance sheet. In order to ensure homogeneity across member states and limit accounting tricks made to comply with the rules of the Stability and Growth Pact, Eurostat has recently made a decision (news release 18/2004) on the accounting of PPPs, which has the power to clarify and make the process of accounting true PPPs more transparent. However, the temptation to adopt PPPs as a tool to window dress budget deficits has not been fully removed.26

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

24 See also the informal discussion in De Bettignies and Ross (2004).

25 See Maskin and Tirole (2007) for a study on optimal public accounting rules when the official's choice among projects is biased by ideology or social ties or because of pandering to special interests.

26 According to the 2004 Eurostat's decision assets involved in a PPP should be classified as non-government assets, and therefore recorded off balance sheet for government, if the private partner bears the construction risk and at least one of either the availability risk or the demand risk. Otherwise, the assets should be classified as government assets.