5 Bundling Financing and Operating Tasks

The relationship between investment and their financing is particularly critical for infrastructures. On the one hand, PPPs projects have recently attracted much attention among financiers because those investments are known as providing stable returns which, to a large extent, are uncorrelated with the market. On the other hand, an often heard benefit of PPPs is that they might bring in the expertise of outside financiers in evaluating risks. In this respect, bundling the task of looking for outside finance (be it through outside equity or debt) and operating assets could improve on the more traditional mode of procurement where the cost of investment is paid through taxation and investment is not backed up by such level of expertise within the public sphere.

To address those issues, we build on the basic moral hazard model highlighted in Section 2. To focus on the benefit of bundling operation and financing, we assume b = 0 so that, there are no social benefit of designing a better infrastructure.

To model the transaction costs that might still arise when the operator looks for outside finance, we assume now that financiers have expertise to get access to some informative signal y on the contractor's effort:

y = e + η | (18) |

where η is a random variable which is assumed to be normally distributed with variance σ2η and zero mean. Of course, using such informative signal may be quite useful as we already know from the Informativeness Principle.27

We investigate in turn the case of public finance where the investment is levied by taxation and the case of outside private finance.

Public finance: Consider first the case where the government itself provides funds to cover an investment outlay of size I. The government does not observe the informative signal y and implements only the second-best effort euSB.

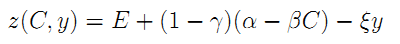

Outside finance: Consider now the case where the operator has full control over his access to the financial market on top of control over operations. To fix ideas, suppose that the operator still receives a linear scheme t(C) = α-βC from the government. Given the contract that is assumed observable by outside financiers, the contractor and those financiers agree on how to share the associated remaining risk.

Let us thus denote by  the fraction of the firm's reward that is kept by the operator. Because outside financiers can condition how much repayment they request from the firm on the extra signal y that they observe, a general linear scheme for repayment can be written as:

the fraction of the firm's reward that is kept by the operator. Because outside financiers can condition how much repayment they request from the firm on the extra signal y that they observe, a general linear scheme for repayment can be written as:

where the term ξy (ξ > 0) is a bonus in case the signal on the firm's effort is high enough. Since financiers are competitive, the fixed-payment E is the price of equity they hold in the project net of the investment cost I.

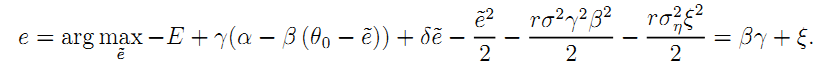

Given those schemes, we can rewrite the operator's incentive constraint as:

| (19) |

This incentive constraint highlights two important features. First, only a fraction of the incentive power of the government's scheme ends up being useful to foster effort because of subsequent risk-sharing between the firm and financiers. Second, financiers can improve incentives by conditioning the firm's repayment on the informative signal they get on its effort.

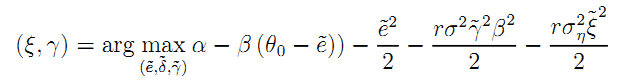

Going backwards, let us turn now to the design of the overall repayment scheme given the transfer scheme with the government. Because financiers are competitive, this repayment maximizes the certainty equivalent of the operator's payoff taking into account the moral hazard incentive constraint (19):

| (20) |

subject to

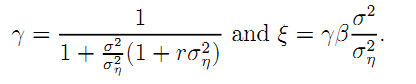

The optimal repayment scheme designed by financiers is straightforward. The share of risk left to the operator is independent of the government's scheme. The firm gets positive bonus in case y is good news on the firm's effort:

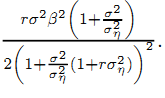

This corresponds to a risk-premium borne by the operator which is worth

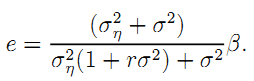

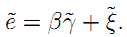

Finally, the effort level implemented by the operator when one compounds the impact of government's and the financiers' contracts can be written as:

| (21) |

This condition can be viewed as the incentive constraint that applies to the coalition between the operator and its financiers.

Notice that this effort level converges towards β when σ2η converges towards zero. When the financiers have a very informative signal on the firm's effort, there is no further dilution of incentives within their coalitional agreement: Effort is efficiently set within the firm/financiers coalition. Instead, when σ2η converges towards infinity, the effort level converges towards  which captures the fact that part of the incentives given by the government are dissipated through further risk-sharing with financiers.

which captures the fact that part of the incentives given by the government are dissipated through further risk-sharing with financiers.

Comparing with the results under public finance, we observe that moving towards private finance unambiguously raises incentives and moves the outcome closer to the first-best.

Result 9 Bundling private finance and operation is optimal when outside financiers have access to some informative signal on the operator's effort level. The power of incentives unambiguously raises and aggregate welfare improves with respect to public finance.

The intuition for this result is straightforward. Relying on outside finance makes the operator less risk-averse, even though outside finance may exacerbate moral hazard by introducing further risk-sharing. The point is that, as the financial contract is made under a better information structure, the extra round of contracting with financiers has more benefits in terms of improved incentives than costs in terms of modified risk-sharing. Intuitively, everything happens as if the government itself was enjoying the financiers' expertise.

Remark 2: Market power on the financiers' side. Suppose now that financiers have specialized in analyzing infrastructure risk. First, such financiers are likely to have market power when designing financial contracts with operators. Second, those financiers might not be fully diversified if a large part of their financial activities come from the infrastructure sector. It is unlikely that, in such environment, the government can recoup all benefits from the financiers' expertise. A double-marginalization problem might occur with both the government and financiers willing to reduce the firm's effort. There will be a trade-off between the benefits of the financiers' expertise and the extra distortions that financial contracts might bring.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

27Holmström (1979).