7.2 Cost Overruns

Long-term contracting takes place under major uncertainty on the realizations of future costs and demand. In infrastructure projects and maybe due to competitive pressures in awarding projects, contractors are often overly optimistic in estimating future costs, as empirically shown by Flyvbjerg, Skamris Holm and Buhl, (2002) and Gannuza (2007). Based on a sample of 258 transportation infrastructure projects worth US$90 billion and representing different project types, geographical regions, and historical periods, the authors found with overwhelming statistical significance that the cost estimates used to decide whether such projects should be built are highly and systematically misleading. Following costs overruns, long-term contracting may be subject to significant renegotiation in those environments. Firms may obtain a tariff increase or an increase in the number of cost components passed through tariffs, a reduction in their payment to the public sector and delays and reduction in investments.

To model cost overruns in a nutshell, we will simplify the modeling of Section 7.1, neglect the investment issue or the building stage of contracting and instead focus only on the hazard coming from uncertainty on costs. To model this uncertainty, we follow equation (24) and the description of cost realizations that follow.

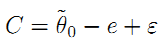

Although, it may not be known ex ante at the time of contracting, the base cost level #0 is later on privately observed by the firm so that there is now asymmetric information. Asymmetric information allows us to consider the strategic incentives of a firm to exaggerate its costs and pretend that costs overruns occur along the course of the contract. To model asymmetric information between the operator and the government, we assume now that costs can be written as:

| (24) |

where we suppose that the base cost level  is random and may be either high,

is random and may be either high,  with probability

with probability  or low,

or low,  with probability

with probability  (denote

(denote  ).

).

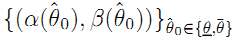

An incentive mechanism must now not only induce the firm to choose a high level of effort but also to induce it to reveal private information ex post, once it knows it. From the Revelation Principle, there is no loss of generality in restricting the analysis to direct revelation mechanisms which consist of a pair of contracts  stipulating a fixed fee

stipulating a fixed fee  and a share

and a share  of the cost borne by the firm as a function of its report

of the cost borne by the firm as a function of its report  on its innate base cost level. Since, for any slope of the incentive scheme

on its innate base cost level. Since, for any slope of the incentive scheme  , the firm always choose an effort level given by e =

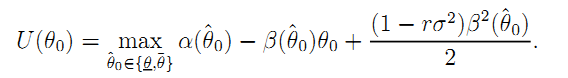

, the firm always choose an effort level given by e =  , we may define the certainty equivalent of the firm's expected utility when knowing θ0 as:

, we may define the certainty equivalent of the firm's expected utility when knowing θ0 as:

| (25) |

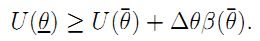

Taking the profile of rents and slopes of the incentive schemes  as the true primitives of our problem allows to write the truthtelling constraint for "an efficient firm as:37

as the true primitives of our problem allows to write the truthtelling constraint for "an efficient firm as:37

| (26) |

This constraint is necessary to avoid strategic cost overruns, i.e., incentives for the contractor to inflate his costs.

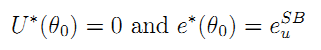

Note again that the optimal solution consisting in offering a rent/effort profile given by

|

|

that would be offered had θ0 been contractible can no longer be implemented because an efficient firm would exaggerate strategically its costs. Cost overruns are then an equilibrium phenomenon for such badly designed contract.

To avoid cost overruns, the truthtelling constraint (26) must be binding at the optimum. This requires to create some risk in terms of the certainty equivalents that the firm may get ex post when knowing its innate cost. This increases the risk-premium that society has to bear to induce the firm's participation and it requires to make the firm's payoff less sensitive to the value of its innate costs. This is obtained by distorting downward e(θ) below its complete information value, i.e., by giving to an inefficient firm a contract tilted towards a cost-plus contract. The cost of such contract is low powered incentives, but its benefits is that it prevents efficient firms to engage in strategic cost overruns.

We can summarize the analysis as:

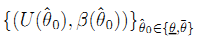

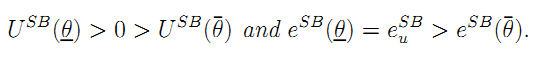

Result 12 With ex ante uncertainty and ex post asymmetric information on the realization of future costs, strategic cost overruns are a concerns. The optimal menu of incentive contracts that prevent cost overruns calls for less powered incentives to the less effcient firm and incomplete insurance visà-vis the realizations of the innate cost level:

Remark 7: Cost overruns and bundling. Of course, reducing the powered of incentives on cost management to avoid strategic cost overruns makes it less valuable to bundle construction and management in an extended multi-task version of the model that would follow Section 2. This does not at all mean that bundling is no longer optimal. Indeed, cost overruns also occur with the more traditional mode of contracting and would shift

the power of incentives in cost management exactly in the same direction. We conjecture that a priori, a positive externality between construction and management would still be conductive to bundling even with cost uncertainty38

Remark 8: Cost overruns, renegotiation and the soft budget constraint. The optimal contract found above is not renegotiation-proof once θ0 is known. Indeed, to induce revelation information by the most efficient firm, this contract requires that an inefficient one makes a loss. This creates an incentive for the least efficient firm to stop the ongoing project if its innate costs turn out to be high. Anticipating this outcome, the principal may not be able to refrain from instilling more subsidy to ensure that even the worst firms will break even; another instance of the soft budget constraint fallacy. Such possibility for renegotiation is thus akin to assuming that the firm is protected by a pair of interim participation constraints ensuring it breaks even for each realization of its innate costs:

| (27) |

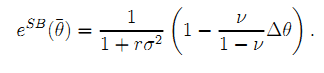

Such constraints harden the trade-off between incentive and participation constraints. It can be easily seen that only the firm with type  obtains now a positive expected payoff and the corresponding distortion of his incentive contracts are exacerbated leading to a large effort distortion given now by:39

obtains now a positive expected payoff and the corresponding distortion of his incentive contracts are exacerbated leading to a large effort distortion given now by:39

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

37 We only focus here on the relevant upward incentive constraints where the low cost firm wants to exaggerate its innate cost.

38The key logic behind that conjecture is that the truthtelling incentive constraint is "orthogonal" to the moral hazard incentive constraint. Suppose instead that, the firm has private information on the size of the externality across tasks and that cost overruns come from the overestimation of that externality. Then inducing truthtelling requires reducing the benefit of bundling tasks which may justify unbundling. We leave the investigation of those issues for further research.

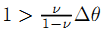

39 Again assuming that  to maintain a positive effort.

to maintain a positive effort.