8 The Roleofthe Institutional Framework: Regulatory and Political Risks

The non-stationary path of incentives described in Result 11 is of course highly dependent of G's ability to commit to increase subsidies in the second period to reward F's initial investment. Assume now that such commitment power is absent and that renegotiation takes place at date 2 with G still having all bargaining power at that stage and extracting, through an adequate fee, all surplus that F could withdraw from renegotiation.

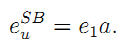

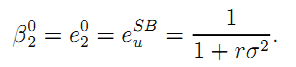

When date 2 comes along, F's investment a0 is sunk and the second period cost reimbursement rule is renegotiated to reach the optimal trade-off between maintenance effort and insurance that would arise in a static context, i.e., conditionally on the investment level a0 which was previously sunk.41 This yields the standard expressions for the second period maintenance effort and the slope of the renegotiated incentive scheme:

Under limited commitment, G can still adjust the second-period fixed-fee to extract all surplus of the firm given his expectation over the investment level a0 at this date and, of course, expectations are correct in equilibrium.

Anticipating the slope of date 2 incentive scheme, and knowing also the slope of the first-period incentive scheme, F chooses his investment so that

| (28) |

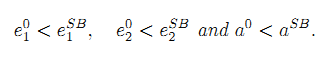

With an opportunistic principal, welfare is lower than with full commitment. More-over, the second-period contract entails lower powered incentives than under full commitment because the second-period incarnation of G does not take into account the impact of the contract he offers on the firm's incentives to invest at date 1. Since e02 = euSB < e2SB, (28) implies that the firm enjoys less of the benefits of investment. To maintain incen-tives for investment, the firm must be even more reimbursed for its first-period costs than under full commitment which moves first-period incentives even further towards cost-plus contracts.

Result 13 With an opportunistic principal, investment is lower and cost-reimbursement rules are even more tilted towards cost-plus contracts in both periods than under full commitment:

Assume now that renegotiation takes place at date 2 only with probability p. This might model settings where the identity of the government may change between dates 1 and 2 with some probability due to elections or where exogenous events occur that induce the current government to renege. In some cases, PPP contract clauses seek to insure the private operator against aggregate risks, but episodes have occurred where governments have reneged on these clauses when a severe macroeconomic crisis occurred. The assumption of limited commitment fits quite well settings with weak enforcement power which may characterize developing countries.

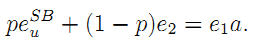

In our setting, when date 2 comes along, F's investment a0 is sunk and with probability p the second period cost reimbursement rule is renegotiated to reach the optimal trade-off between maintenance effort and insurance conditionally on the investment level a0. This yields an expression of the firm's incentive constraint which mixes (A. 12) and (28):

| (29) |

The effort levels in this model with political risk are intermediary between the full commitment and the case of an opportunistic principal viewed above.

Result 14 An increase in regulatory risk (i.e., p greater) lowers incentives for investment in asset quality and induces more low powered incentives.

Literature : The model above considers a renegotiation led by the government with the possibility of breaking an initial agreement. In a sense, the intertemporal incentive scheme is thus closer to a sequence of short-term contracts. In a two-period principal-agent model with short-term contracting and pure adverse selection, Laffont and Tirole (1993, Chapter 9) formalized the so-called "ratchet effect". This effect refers to the possibility that an agent with a high performance today will tomorrow face a more demanding incentive scheme, an intertemporal pattern of incentives similar to the one highlighted in Sections 7 and 8 above. The ratchet effect leads to much pooling in the first period as the agent becomes reluctant to convey favorable information early in the relationship. In our model the emphasis is on moral hazard, and the corresponding pattern of incentives induces the agent to invest less in early periods. In the context of PPP contracts, this effect partially nullifies the benefits of bundling and suggests that PPPs should be preferred in stable institutional environments.

Closer to the analysis of Section 8 but still in a pure adverse selection framework, Aubert and Laffont (2002) analyzed the mechanism through which a government can affect future contracting by distorting regulatory requirements to take into account possible political changes and subsequent contract renegotiation. Assuming that the current contract binds all future governments, imperfect commitment yields two main distortions. First, the initial government will delay the payment of the information rent to the second period, thereby free-riding on the cost of producing a higher quantity and leaving higher rents. Second, the degree of information revelation in the first period will be strategically determined to affect the beliefs of the new government.42

A number of political motives have been proposed to explain the interests of the public-sector party itself in reneging PPP contracts. The government may increase its chances to be re-elected by expanding spending or by promoting investment in public works that create jobs and boost economic activity (Guasch, 2004). By reneging, the government may also circumvent the opposition's scrutiny and reap the political benefits resulting from higher present spending, e.g. a higher probability of being re-elected (Engel, Fisher and Galetovic, 2006).

Applications: Institutional quality plays a critical role in the provision of public services by the private sector. Hammami, Ruhashyankiko and Yehoue (2006) indeed found that private participation (in the form of PPP, privatization or traditional procurement) is more prevalent in countries with less corruption and with an effective rule of law. For PPP contracts the benefit of whole-life management cannot be realized in the absence of strong governance and minimal risk of unilateral changes of contract terms by the government.

Governments' failure to honor the terms of concession contracts is a pervasive phenomenon. In Latin America and Caribbean Countries, it is common for a new administration to decide not to honor tariffs increase stated in the concession contract granted by previous administrations. Examples include the Limeira water concession in Brazil which was denied a tariffs adjustment provided by a contract signed by a previous administration. There are also cases where legislation was passed to nullify contractual clauses. The Buenos Aires water concession indexed local-currency denominated tariffs to the US dollar to protect the contractor against currency risk. However, after a devaluation of the local currency, Congress passed an economic emergence law that nullified these guarantees (Lobina and Hall, 2003). Using a sample of 307 water and transport projects in 5 Latin American countries between 1989 and 2000, Guash, Laffont and Straub (2006) found that 79% of the total government led renegotiations occurred after the first election that took place during the life of the project. In many cases the central or local government during a re-election campaign decided in a unilateral fashion to cut tariffs or not to honor agreed tariff increases to secure popular support.

Political risk has also played a crucial role in Central and Easter Europe. As reported by Brench, Beckers, Heinrich, and von Hirschhausen, (2005), a major obstacle to the PPP policy in Hungary was the frequent change in political attitudes towards PPPs and user tolls. Since 1990 each change in government resulted in a different attitude and a different institutional framework for PPPs.

The impact of regulatory risk in PPPs is significant as it discourages potential investors and raises the cost of capital and the risk-premium (higher tariffs, or smaller transfer price) paid for a PPP contracts. Guasch and Spiller (1999) estimate that the cost of regulatory risk ranges from 2 to 6 %age points to be added to the cost of capital depending on country and sector. An increase of 5 %age points in the cost of capital to account for the regulatory risk leads to a reduction of the offered transfer fee or sale price of about 35% or equivalently it requires a compensatory increase in tariffs of about 20%. Regulatory risk also discourages investors. In the £16 billion London Underground project of 2002-03 a high level of political controversy made lenders nervous, with the result that 85% of the debt had to be guaranteed by the public sector at a fairly late stage in the procurement process.

Renegotiation by the government of concession contracts in Latin American and Caribbean Countries is also widespread. Considering a compiled data set of more than 1,000 concessions granted during 1985-2000, Guash (2004) showed that 30 % of the concessions were renegotiated and in 26 % of the cases, the government initiated the renegotiation. Using a data set of nearly 1000 concessions awarded from 1989 to 2000 in telecommunications, energy, transport and water, Guash, Laffont and Straub (2008) showed that the probability of firm led renegotiation is positively related to the characteristics of the concession contract among other things. Firm-led renegotiation on average tend to favor contractors. Guash, Laffont and Straub (2006) showed that the role of an experienced and independent regulator (or in general the quality of bureaucracy) is especially important in contexts characterized by weak governance and high likelihood of political expropriation. In LAC countries, regulatory agencies were rarely given training and instruments adequate to their mandate and even lacked political support from the government.

To improve governance, a number of countries have created dedicated PPP units - centre of expertise - to manage the contract with the private contractor.43 Different approaches have been taken with regard to the governance of these units as some of them have been set up within the public sector (e.g. Central PPP Policy Unit in the Department of Finance 1 in Ireland or the Unita' Tecnica della Finanza di Progetto in Italy), others outside (Partnership UK in the UK which is a joint venture between the public and private sector with a majority stake held by the private sector).

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

41One word of clarification on the space of contracts allowed is needed at this stage. Indeed, at date 2, the investment level a is private information for the firm. This suggests two things: First, the second period renegotiated contract should allow for screening this piece of information; second, anticipating this screening possibility the firm should create endogenous uncertainty by randomizing among several possible levels of investments. This would certainly bring our analysis closer to the framework of renegotiation under moral hazard due to Fudenberg and Tirole (1990) but at the cost of much complexity. Even if such larger class of second period contracts was allowed, we feel rather confident that the insight that we develop in this section, namely the sytematic move towards cost-plus contracts, would be preserved.

42Other kinds of political risks have been considered in the literature. For instance, Che and Qian (1998) use the property rights approach to show that relinquishing firms' owenrship to local governments may help in a context with insecure property rights where a national government may expropriate owners.

43Bennett and Iossa (2006b) use an incomplete-contract approach to compare contract management by a public-sector agency with delegation of contract management to a PPP that is a joint venture between private and public sector agents. They show that delegation may be desirable to curb innovations that reduce the cost of provision but also reduce social benefit.