Introduction

1.1 Safe, reliable and efficient infrastructure networks form the backbone of every modern economy. The UK has well-developed, sophisticated infrastructure networks that have evolved over several centuries. The New River – an artificial waterway – opened in 1613 to supply London with fresh drinking water. The first locomotive-hauled, passenger-carrying railway was pioneered here in 1825 and the backbone of the national rail network was largely completed by 1851. The first high-voltage electricity distribution line was laid in the UK in 1901 (and the bulk of the national grid was constructed in the following five decades). The first underground railway opened in 1863 in London, carrying passengers between Paddington and Farringdon, and work has now begun on Crossrail, one of the largest tunnelling projects in the world.

1.2 Evidence shows that investing in economic infrastructure is important for growth and that, for example, building better transport links and energy generation capacity can have a stronger positive effect on GDP per capita than other forms of investment.1

1.3 Infrastructure can have a positive effect on economic activity through a range of different channels:

• increasing output per hour, including by enabling:

• businesses to sell products to customers more efficiently, e.g. through quicker and cheaper transport of goods, services or data, or lower costs of production;

• businesses to produce higher value products, including new intellectual capital, e.g. through improved facilities for research and innovation; and

• businesses to access larger markets, e.g. through improved links between production centres and ports/airports or through internet sales;

• increasing the number of effective hours worked each year, e.g. by reducing unproductive time and reducing travel times;

• increasing the employment rate, by enabling a greater proportion of the population to participate in the economy, e.g. through improved transport or communication links between suburban and rural areas, and city centres;

• increasing aggregate demand during the construction phase of projects, acting as an important source of employment, skills and innovation in the UK upon which firms can generate export opportunities, particularly to emerging markets;

• unlocking additional investment that relies on the new facilities in order to be viable, e.g. the impacts of enhanced transport connectivity; and

• attracting international investment (and retaining within the UK activity that might otherwise be placed overseas) by influencing decision-makers whose locational decisions will be influenced by the quality and reliability of infrastructure.

1.4 Transport and communications systems can have direct effects on unlocking additional investment and raising levels of productivity.2 The energy, water and waste systems are important inputs into production processes, and their failure can cause significant loss of output. Flood risk management avoids the loss of productive hours from environmental shocks and climate change, both in terms of direct economic losses as well as consequential impacts on transport, energy and communications infrastructure, and interruption of wider public services. It can also open up land for productive economic activity.

1.5 Comparisons are often made between the lower rate at which developed countries such as the US and the UK invest in infrastructure, and that of emerging countries such as China and India. The latter are starting from a weaker base of infrastructure and so have a great deal of catching up to do with developed economies. It is not surprising therefore that their investment rates are higher than those of the UK.

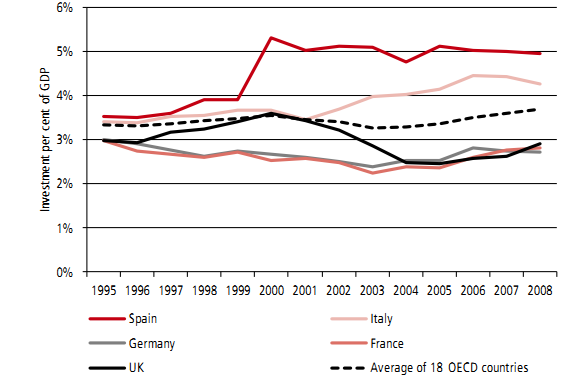

1.6 The UK has tended, over the last 15 years, to invest a similar or greater proportion of its GDP in economic infrastructure (around three per cent on average) as countries such as France and Germany, but since the turn of the century the rate of investment has fallen behind that of the rest of the OECD (see Chart 1.A):

| Chart 1.A: Energy, water supply, transport and communications investment as a proportion of GDP

Source: OECD, International Transport Forum |

1.7 This, combined with evidence that shows new infrastructure projects in the UK continue to exhibit high benefits relative to costs, suggests a degree of recent under-investment in the UK's economic infrastructure. This National Infrastructure Plan underlines the Government's commitment to secure the investment that the UK's economic infrastructure needs.

1.8 The Government estimates that over £250 billion of investment in infrastructure is planned to 2015 and beyond. This is a significant increase over the £113 billion invested in the period from 2005-10.

1.9 However, relative investment rates should not be the only concern for infrastructure policy. It is more important for the UK that its infrastructure remains competitive with major trading competitors, particularly in the OECD. This means maintaining the performance of the UK's infrastructure over time and, where it is comparatively weak, improving performance in line with the best in its peer group. It also means working to ensure that the cost of infrastructure to businesses and households in the UK remains competitive. Together, high infrastructure

performance and low cost will ensure that the UK remains a good place in which to do business.

1.10 Maintaining the performance of infrastructure over time is important not just for the sake of competitiveness, but also as a basic principle of fairness between generations. Applied to infrastructure systems, this principle argues in favour of maintaining a similar level of performance between one generation and the next so that future citizens inherit infrastructure at least as good in quality as the one available to the current generation.

1.11 This National Infrastructure Plan therefore follows three principles:

• to maintain the overall performance of the UK's infrastructure over time;

• to address the UK's weaknesses and catch up with the best performers in the world; and

• to do so in a way that offers the greatest value for money for taxpayers and users.

__________________________________________________________________

1 See Infrastructure and Growth: Empirical Evidence, Egert, B., Kozluk, T. and Sutherland, D., OECD, 2009; Transport infrastructure investment: implications for growth and productivity, Crafts, N., Oxford Review of Economic Policy, vol. 25, number 3, 2009; The Rate of Return to Transportation Infrastructure, Canning, D. and Bennathan, E. in 'Transportation Infrastructure Investment and Economic Productivity', OECD, 2007.

2 The Eddington Transport Study, HM Treasury and Department for Transport, 2006; Infrastructure and Growth: Empirical Evidence, Egert, B., Kozluk, T. and Sutherland, D., OECD, 2009