1.3. Bonds vs bank debt: pros and cons

Although alternatives to public bonds and bank loans are being discussed, for the time being these two solu-tions remain the principal options for debt finance in the PPP market. Despite the use of bond finance for more than a decade, it remains misunderstood by many stakeholders in the PPP market. This section will identify the main ways in which bond and bank financings differ and how one form of financing may be preferable to the other in different areas.

1.3.1. Interest rate on borrowed funds: Although this differs among national markets and over time within markets, the cost of bond financing has been very attractive relative to bank financing in some markets, most notably the United Kingdom. There are a variety of reasons for this. First, the ability of traditional bond investors to lend on a fixed-rate basis eliminates the need for a swap, which can produce savings in the all-in borrowing rate. Second, the greater certainty that bond investors have that the term of their liabilities matches the term of their assets gives bond investors the ability to ascribe a lower cost to liquidity risk. Third, because most bonds have been monoline-guaranteed, they have been issued at triple-A ratings which, even when taking into account the cost of the guarantee, has produced a lower cost of funds than would have been required by banks in many cases.

| Historical monoline pricing - UK market Monoline cost of debt = gilt rate + credit spread on wrapped bond + guarantee fee Example: A PFI hospital project rated Baa3/BBB+ which closed in 2005 was priced with a credit spread of 57 bps over the reference gilt and the monoline fee was 20 bps leading to a total cost of funds of 77 bps over the gilt rate. Because no unwrapped PPP bonds have been issued since 1998, a direct comparison of issue price is not pos-sible, but a comparably-rated corporate bond would have been issued at gilts + ~130 bps during this period, suggesting that the wrapped bond execution presented a significant improvement in the cost of funds (in this example ~53 bps). Although comparisons between issue price and secondary price should be made with some caution, as a further indication of the savings achieved with the monoline execution, the trading range of the unwrapped bond for the Greenwich Hospital PFI project (Meridian) was gilts + 167-183 during 2005, indicating savings in the realm of 100 bps had the unwrapped bond financing been deliverable at that time. Because bonds and bank debt do not use the same base rates (a floating rate such as Euribor or LIBOR, generally swapped to fixed, for bank debt against the gilt rate for bonds), it is not sufficient to compare the spread to the base rate; rather the all-in cost of funds must be com-pared to assess the relative cost of each option. Historically, monoline wrapped bonds have proved highly price competitive with bank debt. Source of corporate bond spreads: iBoxx Sterling non-gilts BBB 10+ years |

1.3.2. Negative carry: "Carry" refers to the interest a borrower receives on funds borrowed prior to using the funds for the purpose of the project, generally construction of an asset in the case of PPPs. Bond financ-ing almost always provides for all of the proceeds of the debt issuance to be drawn by the borrower at financial close, even if all the funds will not be required until later in the construction programme. This requires the borrower to invest the funds until required. In general, the interest rate that the borrower receives is lower than that paid to the bondholders, resulting in "negative carry". In contrast, banks disburse funds to the project company as required, charging a commitment fee on the undrawn amount of the loan facility, but not interest; therefore, there is no need to invest funds at a net negative return. Because PPPs do not usually generate cash flows to the project company until the asset required to provide the service is completed, the negative carry phenomenon requires the project company to borrow more in a bond-financed transaction than in a bank-financed transaction to enable it to cover interest payments during the construction period. In this respect, bond financing is less efficient than bank financing.

1.3.3. Prepayment and the refinancing opportunity: Because of the potential for creating gains by refinancing a project at a cost that is lower than the initial financing cost, the possibility of refinancing a project is of interest to both private sector sponsors and the public sector, which may have a contractual right to share such gains. The initial financing route will have an impact on the likelihood of refinancing because of dif-fering prepayment and breakage costs payable on various financial instruments. It is important to note that breakage costs for financial instruments vary in different markets; therefore, these comments can only be taken as an indication of possible outcomes and practitioners should take specialist advice applicable to their own jurisdictions.

Lower financing costs can arise for two reasons. First, for many projects, the perceived risk of default falls following successful completion of the construction programme, which can result in the ability to refinance the project at a lower credit margin than was available prior to the completion of construction. Second, the general level of interest rates, driven by the government or interbank borrowing rate, may have fallen since financial close, enabling the project to obtain cheaper funding even if the credit risk margin has not decreased. These two factors are independent and may move in the same direction, thereby increasing the potential refinancing gain, or in different directions, in which case the reduction in credit margin may be partially or wholly offset by an increase in the underlying rate.

In a bond financed transaction, on a voluntary prepayment by the borrower, the bond terms will generally call for a prepayment fee in addition to the return of the par amount outstanding. This is usually a sum calcu-lated to enable the bondholder to reinvest the prematurely repaid principal in another instrument at a yield equivalent to that which the bondholder would have earned had the bond not been prepaid. This may be on a risk-adjusted basis or on a risk-free basis as is common in the U.K.

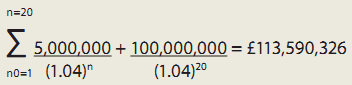

| Example of a bond prepayment cost: "Spens" = a payment to the bondholder that is the higher of the par value of the bond and the present value of the payments on the bond discounted at the then current yield on the UK government bond (gilt) of the same duration Assume: Therefore, annual cash flows = 30 interest pay-ments of £5,000,000 and a final principal payment of £100,000,000 If there is a prepayment at the end of year 10: The amount owed to bondholder without a Spens clause = £100,000,000, representing the outstanding par value of the bond irrespective of prevailing rates at the time of prepayment. But, the amount owed to bondholder with a Spens re-quirement if gilt rate is 4%

Note that the UK practice of using the gilt rate or gilts plus a small margin exacerbates the effect of the yield maintenance provision, but even if the discount rate were kept on the same risk-adjusted basis, the principle of yield maintenance would still eliminate the economic effect of refinancing when interest rates fall. |

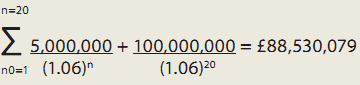

| Example: the "Par floor" effect Assume the same bond as in the previous example, but interest rates have risen since financial close. Amount owed to bondholder with a Spens requirement if gilt rate is 6% =

BUT Because the bond terms dictate that the lowest amount that bondholders will receive is par, the borrower will still pay £100,000,000, not the lower amount derived from the present value of the bond's cash flows at the higher interest rate prevailing at the date of prepayment. |

The effect of such a provision is to make it difficult for a borrower to profit from a lower interest rate environment because the present value of any gain that the borrower would achieve from lower future interest payments would be given up to the existing bondholders to maintain their yield. The yield maintenance adjustment is also gener-ally subject to a floor on the par value of the bonds. This latter feature is not particularly important to the equity providers, a negative yield adjustment implying as it does the unlikely scenario that the bond has been refinanced at an interest rate that is higher than the interest rate on the original financing; however, the par floor is important to the public sector authority which may want to termi-nate the project agreement for reasons unrelated to the performance of the project company (e.g. a change in operational requirements or government policy) and the par floor will produce a windfall to the bondholders in the form of compensation payable by the authority, thereby adding an uneconomic cost to termination.

Bank loans for PPPs have not historically incorporated yield maintenance provisions because they bear a float-ing rate and therefore always track current market rates. (It should be noted, however, that banks have begun to incorporate prepayment fees into their terms in the more constrained current market). The loan-financed project does not, however, have a free prepayment option. Because bank loans bear a floating rate and project company borrowers normally receive fixed periodic payments under the PPP agreement, the floating rate cash flows are generally swapped to fixed rate flows to mitigate the risk to the project company that interest rates rise, leaving it with unaffordable interest payments. On prepayment of the loan, the swap will be terminated and breakage costs arise. This cost is similar in concept to the bond investor's yield maintenance provision with two key differ-ences. First, the breakage costs are always calculated using a discount rate determined on the assumption that the swap counterparty is replacing the forgone cash flows with cash flows from another party of identical risk to that of the party that is breaking the swap. The effect of this is that there is no windfall to the swap counterparty like there is to the bond investor operating in a jurisdiction (like the U.K.) in which the discount rate used is the risk-free rate. Second, the swap breakage sum may be either positive or negative, which means that an authority terminating a project in a non-default situation may have the principal sum owed to the lending bank offset by a negative swap breakage amount, which, as noted above, will not occur in the case of a bond.

Note that the future stream of payments must be estimated to calculate the breakage cost. This is not left to the in-dividual swap counterparty. The process is governed by a standard set of documents used in the global swap market so the breakage costs for any given payment profile are subjected to a market determination procedure. | |||||||||||||||||

1.3.4. Refinancing risk: Prior to the current financial crisis, the term of bank lending was limited by the term of the swaps available. At the beginning of the PPP market, this had been relatively short and projects were limited to terms of 15 to 20 years. The bond market was able to offer terms of 30 years and longer, and over time, the swap market responded with longer terms, enabling banks to continue to compete for projects in which a long term was required to amortize the cost of the assets at an affordable level of payments for the public sector. In the current market, banks will not generally lend for the full term of the project agreement or concession, creating a refinancing risk that must be allocated. To date, generally this risk has been divided between the public and private sector, with the public sector accepting that the cost of margin step-ups incorporated in soft mini-perm loans will be covered by an increase in payments to the project company, and the private sec- tor accepting the risk that under hard mini-perms refinancing will be unavailable at any cost and the project might be terminated following the project company's failure to repay its debt.2)

Bond financing, being drawn from investors having naturally long-term liabilities as opposed to banks with normally relatively short-term funding sources, is still able to offer financing of the same term as the underly-ing concessions, thereby avoiding the introduction of refinancing risk into projects.

1.3.5. Project decisions: PPP projects involve complex contractual arrangements under which many decisions of concessionaires are controlled by lenders. This is true not only when projects have run into difficulties but also when projects are performing as anticipated. Typically, these decisions are contained within a part of the funding agreement known as the "controls matrix". The controls matrix will cite every clause in the project documents under which the project company can or must make a decision and indicate the degree of control that the funders wish to exercise over that decision, ranging from absolute control to no control. The way in which these decisions are made differs between bank and bond funding.

The documentation of bank-funded projects will usually delegate a large class of decisions to the agent bank (or a small committee of banks in some transactions). The syndicate of banks will be called to make decisions of particular importance or in relation to decisions required because the borrower has committed serious breaches of its obligations. The speed of the decision-making process will be directly related to the number of banks in the lending group and can become cumbersome in large projects.

In bond-funded projects, the control issue has evolved around the monoline. Because the monoline takes the front-line risk of project default, bondholders have historically ceded control of decisions to it. This "controlling creditor" role has made it much easier for borrowers to obtain decisions in a bond-funded project because the lender control is vested in a single entity irrespective of the nature of the decision. How decisions would be made in the absence of a monoline is a question facing the markets now. Contractually, without a mono-line, the decision-making authority would lie with the bond trustee; however, in practice, bond trustees will rarely make any decision without consultation with and indemnification from bondholders. This process is impractical in the context of a project financing in which many decisions may be required in a short period.

1.3.6. Certainty: In the pre-crisis markets, a bank solution was providing earlier and greater pricing certainty as bank lead arrangers were still prepared to "underwrite" the deals in advance of financial closing (i.e. guarantee the subscription and the margin over LIBOR/Euribor, in most cases as early as at tender submission), when a capital market issue and its margin over the relevant government bond yield would become effectively committed only at the time of issuance, shortly before or at financial close.

1.3.7. Deliverability: loan syndication vs public bond offering. Despite more than a decade of successful PPP bond financings, it is still sometimes said that bond executions are less certain in deliverability than bank loans, i.e. there is a higher risk that funds may not be available, or available at uncompetitive prices. Historically, however, even when a public bond issue has been more difficult to sell than the arrangers had anticipated, as a reputational matter, the bond lead managers have habitually purchased the unsold bonds for their own account, in the hope of re-selling them later; even though they had no contractual obligation to do so. In the current market, on large projects, a bank loan will require syndication-a process that is similar to a public bond offering and, as recent history has shown, no less likely to fail. The dislocation in the financial markets has revealed that under stressed conditions the loan syndication market is not completely reliable and lead banks have invoked market flex clauses even after financial close, resulting in a higher than expected financing cost for the public sector. On balance, in the current market, syndicated or clubbed bank and bond financings should be seen as presenting similar levels of execution risk.

1.3.8. Cost of issuance: The transaction costs associated with bond financing are higher than for bank financing due to the necessity of obtaining ratings for the debt and the legal costs associated with undertaking the listing of the bonds on an exchange. This difference, however, is insufficient to be a significant factor in the funding route decision.

1. 3.9. Inflation hedge: A specific category of bond, is the inflation indexed bond, where the bond principal is ad-justed for inflation following a defined price index (the way these bonds work is further explained in § 5). These bonds are particularly attractive to investors such as pension funds, which have long term inflation indexed obligations to match. It may equally be of interest to many procuring authorities which are willing to commit to unitary payments at least partially linked to inflation, in line with their budgetary resources. This is another attraction of bonds, as this type of inflation related product is not commonly available in the bank market.

In summary, bond financing has historically been less flexible than bank financing and presents issues of post-closing deal management without the participation of a monoline; however, these disadvantages must be weighed on a case-by-case basis against potential savings in financing costs, the elimination of refinancing risk, and the possibility of financing assets over longer concession periods.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2) A "soft mini-perm" is a loan with a term that amortizes fully over the life of the concession but which contains incentives for refinancing such as margin increases and capture of cash flow that would otherwise be distributed to project sponsors. A "hard mini-perm" is a loan that does not amortize fully and which must be refinanced failing which a payment default will occur.