Equity

The earlier analysis identified two main benefits from equity in PFI which other procurement models might seek to replicate; integration of design, build, maintenance and operation; and long term performance incentives. (There is a third benefi t too - taking pain on project failure - but it is hard to see how, even theoretically, this could be replicated without external investment.)

As noted earlier, the integration benefits could in principle be achieved to some degree through a DBMO model, though the absence of equity to glue various elements of the project together and to give an incentive to achieve successful integration is a weakness. It is perhaps for this reason that there has been little enthusiasm for this model in the UK (see Exhibit 3 below).

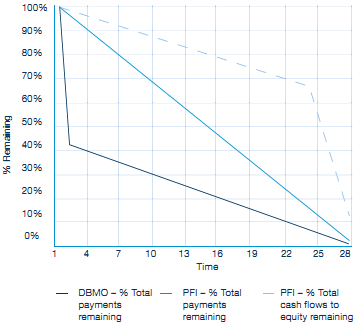

Exhibit 3: Design Build Maintain Operate (DBMO) v Private Finance Initiative (PFI) - (Comparison of a Typical Project)

A design, build, maintain and operate (DBMO) contract is one in which a consortium of contractors provide all the services required for the life of a project and the public sector body provides the finance at the stage at which it is required. Typically this will mean investing the majority of the funding during the construction phase when capital intensive assets are built and then providing smaller sums through the life of the contract to cover the running costs incurred by the consortium. This is in contrast to a PFI project, where the consortium finances the construction of assets and is paid a unitary payment over the life of the project by the public sector body.

Arguably, the integration benefits of PFI could be gained using a DBMO model without the complexities and (some would argue) cost of private finance incurred under PFI.

However, DBMO has disadvantages in terms of risk transfer as it does not have the same financial incentives in the form of returns to equity, to ensure the consortium's long term commitment to the project. If problems were to arise during the operation phase of the contract, the DBMO consortium would have less incentive to spend the money required to fix the problem and would be more likely to walk away from the contract than under PFI on account of the payment profile and the profile of cashflows to equity in particular.

The graph overleaf, comparing typical DBMO and PFI projects, shows that after 5 years of operation, using the DBMO model means that only around 35% of the nominal payments in the entire contract are still owed to the consortium - 65% of the nominal contract value has already been paid. By 20 years, there is only about 12% of the nominal contract value remaining to be paid. By year 20, however, there are still around 75% of the cashflows to equity remaining under the PFI model. If exceptional costs were to occur in, for example, year 10 of the contract, the consortium has far less incentive to pay those costs to maintain the project under DBMO, where it has only 30% of the nominal contract value still owed to it, than under PFI, where it still has nearly 70% of the nominal value of the contract owed to it and 85% of the cashflows to equity still due to it. Thus, under PFI, the consortium appears to have a greater incentive to maintain the facilities and to build a better quality of asset in the original construction than under DBMO.

Percentage of total nominal cash flow remaining in a typical DBMO and PFI model and percentage of total cash flows to equity remaining in a PFI model

The beneficial impact of equity on long term performance management could, it might be argued, be replicated through carefully designed long term operating contracts. Indeed, it is not easy to disentangle, even within PFI projects, the effects on performance of equity and of a well structured payment mechanism. Whether or not equity makes a distinctive difference could be definitively tested either way only by comparing samples of PFI contracts with long term operating contracts in similar sectors. Unfortunately, there are few such comparators. While the public sector have fewer medium/long term operating contracts they have mainly been for IS/IT related services, an area in which there have been very few PFI comparators.

In the absence of much, if any, directly relevant empirical evidence, can any inferences be drawn from the application of first principles? One, perhaps. The normally back ended profile of equity cashflows means that equity remains exposed until the very late stages of a project. This degree of financial exposure is generally greater than that which could be achieved by heavily performance- related payment mechanisms in an operating contract, especially given that any payment deductions under such contracts must not, as a matter of law, be so harsh as to constitute a penalty. This is illustrated by the further comparison of the profile the cashflows to equity under a typical PFI project with the service payments under a DBMO contract (see graph in exhibit 3).

Financial exposure is not, of course, the only incentive for long term performance management. The consequences of poor performance on reputation, and on obtaining further business, are powerful too. But in large and very long term contracts the financial incentives within the contract itself must be very powerful. This suggests that, when a body of empirical evidence comparing projects with and without equity is available for analysis, it will be surprising if it does not show the equity has a special role to play in ensuring high quality long term performance.