Refinancing risk support

As long as finance and swaps for PPP projects have tenors substantially less than the project duration, there will be a need for refinancing, as the project debt finance cannot sensibly be repaid within the short tenors available. This refinancing poses a significant risk. The problem is that equity investors and project lenders are likely to be conservative, due partly to the high gearing of PPP projects, with limited equity to absorb this risk. Consequently, if they are willing for PPP Co to bear the refinancing risk at all, they build large risk margins into their proposals against interest costs rising, adding to the cost of the project and worsening its value for money to the government. Higher interest costs pushing PPP Co into financial difficulties also would create a political problem for government. There is also a political risk should interest costs fall, giving a windfall gain to the private sector, even if the government shares equally in this gain.

A sensible compromise would be for government and the private sector to share the refinancing risk. Many governments already bear this risk (or manage it on a portfolio basis) for their own borrowings and those of state-owned enterprises.

In practical terms, the risk of finance not being available at the maturity of the initial debt is very low (provided no extra finance is required). Existing lenders effectively are locked into their lending commitments once funds have been advanced. Provided the project is performing acceptably, they will be reluctant to exercise their security and take control of PPP Co, because of the damage this action would do to their relationships with the equity investors, and because of the resources that they would have to devote to managing PPP Co.

The practical refinancing risk is that finance costs increase from those originally projected. This risk applies both to interest margins, fees, etc. and to swap rates. From a government perspective, the private sector needs to have some incentive to manage its finances efficiently, so needs to bear some of this refinancing risk.

However, the risk of substantial market changes similar to those that occurred over the last 2 years (as shown in Table 1 above) probably is beyond the capacity of the private sector to absorb fully.

So how might refinancing risk sharing work? Compare the refinancing risk to the insurance cost risks that emerged following the terrorist attacks in New York in 2001 and therein lies a potential solution to the problem. In both cases, the risk event (a change in finance or insurance costs) is almost entirely outside the control of PPP Co, so it should not suffer excessively nor profit from the event. However, there needs to be an incentive on PPP Co to seek the best value finance, particularly if finance costs have increased.

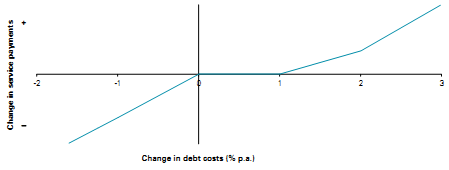

The risk sharing mechanism, shown in Figure 4, applies to increases in total debt finance costs above those assumed in the project financial model. (Front-end fees are amortised over the term of the debt and added to interest costs.) PPP Co bears the full risk of cost increases up to a pre-defined threshold (say, 1 percent p.a.). Between this threshold and a second threshold (say, 2 percent p.a.), the government bears a proportion (say, 40 percent) of the additional debt finance cost, through an adjustment to Service Payments. Where debt finance costs exceed the second threshold, the Government bears the large majority (say, 80 percent) of the additional costs, leaving PPP Co to bear the remaining 20 percent.

The appropriate structure will depend upon government's appetite for risk and may need to be adjusted if, for example, the private sector is willing to take an optimistic view of future interest costs.

Transparency is essential if this mechanism for sharing the downside risks of refinancing is to work. Refinancing offers from lenders would have to come from a competitive process. In addition, government would need to agree to key structural features, particularly tenor, given prevailing market conditions.

Figure 4: Refinancing risk sharing mechanism

This mechanism deals with sharing the downside of the refinancing risk. Any improvement in financing terms could be handled slightly differently, given the potential for windfall gains to the private sector, with the government receiving the majority (say, 75 percent) of the benefit of all lower debt finance costs. The government could have the right (as in the UK) to require an early refinancing should market conditions improve.

In the past, governments often have only shared in any refinancing gain if equity returns exceed their Base Case levels following the refinancing, to avoid diminishing the benefit of a rescue refinancing. However, rescue refinancings generally focus on higher gearing or increased economic tenor, rather than lower debt finance costs, so this risk sharing approach would not apply. Instead, refinancing gains resulting from higher gearing or increased economic tenor would be managed in the normal way, with government sharing only in any equity upside.