Canada's Foreign Direct Investment Challenge

Canada has lost its lustre as a destination for foreign direct investment (FDI). But not because of increased inflows of FDI to China, India and other developing countries. The facts are that developed economies overall were able to increase their share of the growing global stock of inward FDI from 56.0 per cent in 1980 to 64.5 per cent in 2002.1 In contrast, Canada's share of the global stock of inward FDI fell from 7.7 per cent in 1980 to 3.1 per cent in 2002. Canada's strategic advantage has diminished due to trade liberalization, the rise of global supply chains and the decline in the relative importance of resource commodities in the global economy.

Canada must do a better job of attracting FDI in order to improve its competitive position and economic potential. Achieving that objective demands a better understanding of the trends in global direct investment and the factors affecting Canada's ability to attract FDI.

The purpose of this report is to provide insights into the global trends in FDI, the reasons for Canada's poor performance and possible actions that Canadian governments can take to make this country more attractive as a destination for global direct investment. Decisions on investment destinations are made by executives in multinational corporations; accordingly, the research for this report included a survey to discover how such decision-makers view Canada as a place in which to invest.

Attitudes toward foreign direct investment have changed considerably over the past 30 years. In the 1970s, Canada was so wary of FDI that it created the Foreign Investment Review Agency (FIRA) to screen inward direct investment and, in so doing, maximize its benefit. Canada was not the only country to harbour deep suspicions about foreign investors; many countries limited foreign direct investment or banned it entirely in designated key sectors. Since then international opinion has shifted, so that today the prevailing belief is that the benefits of foreign investment greatly outweigh its drawbacks. In Canada, this shift was reflected in the transformation of FIRA into Investment Canada, which has a mandate to encourage foreign investment.2

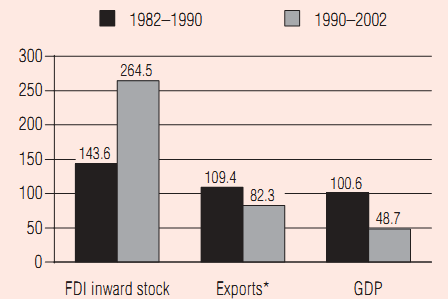

With the decline in the restrictive atmosphere worldwide, the volume of foreign direct investment has grown rapidly. As Chart 1 shows, growth in foreign direct investment has outpaced growth in both international trade and global economic output during the past two decades. Moreover, FDI has become one of the primary mechanisms for integrating the world economy.

The ability to attract and keep foreign direct investment is now recognized as one of the building blocks of economic success.3 As a result, competition for the global supply of direct investment has become intensely challenging: the European Union and United States continue to be major recipients; new direct investment in the former communist countries and some developing countries has become important (agencies such as the World Bank actively encourage and coach developing countries in attracting foreign direct investment); and, with growing global recognition that inward foreign direct investment is beneficial, most countries have revised policies and practices to make them more attractive to FDI.4 In short, Canada has many new and aggressive competitors for the attention of global investors.5

| Chart 1 World Growth in Selected Economic Indicators (per cent) |

|

|

| * Exports of goods and non-factor services. |

| Methodology This research project included an analysis of the literature and data, a survey and interviews with executives in foreign multinational enterprises. The survey was conducted between November 2003 and February 2004. Companies and names of executives were drawn from the global list of The Conference Board Inc. (New York) and The Conference Board of Canada. Executives who participated were at the level of vice-president or higher and were directly involved in making foreign direct investment decisions, as CEOs, CFOs or senior managers of investment strategy or international operations. The survey was administered to two sets of respondents: executives from the head offices of foreign multinationals and from Canadian subsidiaries of foreign multinationals.1 About 65 per cent of respondents were from U.S. multinationals, with the rest from Western Europe (mainly the United Kingdom and France). In general, foreign head offices represented 60 per cent and Canadian subsidiaries the balance of the total responses. Depending on the question, total responses ranged from 79 to 106. Survey results for each question were estimated as a weighted average (of the two sets), so that overall results could be presented in pie charts. The combined sample has a statistical significance of more than 90 per cent or an accuracy rate of more than 18 out of 20. The survey was complemented by 18 interviews with a selection of senior executives from foreign multinationals in the United States and Europe and from foreign-owned Canadian subsidiaries. About 55 per cent of the participating companies employed more than 10,000 workers, and about 70 per cent had assets of more than $1 billion. Companies represented a wide range of businesses, but most were in the finance, insurance, information technology and manufacturing sectors. Seventy-four per cent had foreign operations in more than four countries. Thirty per cent had been operating in Canada for more than 10 years, with 45 per cent established in Canada for more than 30 years. 1 Of the foreign multinational respondents surveyed, 35 per cent had no investments in Canada and 71 per cent had no interest in investing in Canada at this time. |