5. State Guarantee of Private Debt

An alternative form of state support for PPP projects not widely used in Australia is the issue of state guarantees or indemnities to support privately sourced project finance. The guarantee may be conditional or unconditional, full or partial, permanent or reducing, medium or short-term and it may impose on the indemnified bank positive covenants designed to preserve the contract performance, monitoring and loan administration roles that lenders assume under traditional project finance arrangements.

A state guarantee can be viewed as a trade-off in project and service delivery risks. Conventional PPPs transfer most project risks to the SPV. The state may retain full or part responsibility for site conditions and residual political risk, which principally concerns service delivery failure. Responsibility for asset delivery, operational performance and financial risk vest in the SPV and step-in rights vest in the lender in the event of default under either the SPV's agreement with the state or the loan agreement. Under a state guarantee arrangement, the state assumes a contingent liability for the SPV's default under either agreement. Under a traditional procurement, subject to specific risk transferred to contractors, the state carries ultimate responsibility for infrastructure service delivery and the multiplicity of risk that this involves.88 The benefit of state allocation of risk to the SPV is improved value for money. A state debt guarantee increases risk borne by the state in the form of contingent liability for the secured debt component in the event of SPV default under the loan agreement. This risk should be measured and incorporated into the PSC. If the quantitative VFM result is positive, the decision to proceed with a PPP is justified.

The guarantee risk has two elements - the probability of the guarantee being called and the cost to the state if it was. The probability of default is greater with economic infrastructure and particularly those projects that feature market risk than it is with social infrastructure. The two economic infrastructure projects that failed in Australia were the Airport Rail Link and the Cross-City Tunnel PPPs in Sydney. In both cases, the SPV overestimated patronage levels and shortly after opening, both operations moved into administration with financiers exercising step-in rights and assuming management of the assets. The Cross-City Tunnel was sold and refinanced and is currently performing to expectation. No significant loss was incurred by lenders to the project with losses absorbed by equity investors. The state carried partial patronage risk in the Sydney Airport Rail Link project and the project remained under administration until 2006 when it was sold to an institutional fund manager, Westpac.

The La Trobe Hospital in Melbourne and the Deer Park correctional facility were social infrastructure projects that encountered performance and operational problems in Victoria. In both cases the state repurchased the assets at less than replacement value. Other PPPs that struck problems were Southern Cross Station (delivery time and cost), Port Phillip Correctional Facility (operational performance), Enviro Altona (failure of the parent company) although none of these projects resulted in service delivery failure or high cost to the state.

In the projects that were negotiated as surrender of the franchise, losses were incurred by equity investors and no significant loss was incurred by lenders and in all projects, service delivery was maintained.

The distinction between economic and social infrastructure projects is important. Economic infrastructure in the form of land transport projects that include patronage risk possess the greatest overall risk profile. International evidence and research over 20 years confirms that, on average, most transport projects achieve an average 70% of forecast patronage and that level of error has persisted for decades.89 Rail projects experience higher forecasting error than road projects and market risk increases the likelihood that the state will face a call under the guarantee. This is demonstrated in the Sydney Airport Link Rail PPP in which the state retained partial patronage risk. 90 Patronage risk in most land transport projects is held by the SPV.

In the case of PPPs for social infrastructure, the fundamental risk to the state is service delivery failure and asset utilisation. The state is the source of the unitary payment under the contract and can use this to mitigate obligations arising under a guarantee of private debt.

A further consideration is whether the value for money benefits of PPPs exceeds the risk-weighted cost of traditional procurement including a fully-costed guarantee. International evidence suggests that projects with an underlying Standard and Poor's credit rating at AAA or AA grade have a almost negligible risk of default. The risk increased to 3.4% at BBB and 9.7% or more at less than investment grade.91

Debt guarantees in the form of a present obligation that may, but probably will not, require a payment in the future are accounted for as a contingent liability and noted in the financial reports of government agencies.92 Where the present obligation "probably requires" a future payment by the state, the guarantee is recognised as a provision and disclosed as such in the agency's financial reports.93

In Australia, public agencies entering into concession arrangements for the supply of goods or services are required to disclose their interest.94 The disclosure requirement is determined by a control test whereby (a) the grantor controls or regulates what services the operator must provide, to whom it must provide them, and the prices or rates that can be charged for services; and (b) the grantor controls the residual interest in the property. Shading-in provisions apply to partly qualifying arrangements. 95 These changes will amend present Loans Council practice whereby obligations arising under concession agreements are not taken into account in Loan Council allocations each year. 96 Nevertheless, such arrangements are disclosed as contingent liabilities. 97 In 2009, the Ministerial Council foreshadowed a wider role for the Loan Council in financial arrangements for the provision of infrastructure.98

A guarantee may take several forms. It may be a partial, capped, conditional or an unconditional guarantee of a loan for all moneys owing or specific obligations such as loan principal repayment, payments of accrued and/or future interest, the guarantee of future capital charge payments by the state, a guarantee against specified political risks such as changes in taxation law or guarantees relating to revenue or tariffs.

The guarantee of a bank loan implies that the cost of debt capital will be any less than a conventional PPP transaction with credit enhancement. This can be expected to be offset or exceeded by a state guarantee fee. However, it does change the credit risk of the underlying transaction to the bank and will attract a smaller risk spread than for AAA rated monoline insurers. It should also reduce transaction and agency costs. However, it may impair the important incentive framework under which the bank monitors service delivery, compliance with the concession agreement and administers the loan agreement with the SPV. However, this effect may be no different than already applies under credit enhancement arrangements.

From the state's perspective, the advantage of a guarantee over direct lending is that it does not attract deadweight costs or transaction fees, and it may not have an adverse impact on state debt levels.99 Transactional and agency responsibilities can be transferred to the lending bank together with governance and reporting obligations. A state guarantee in these circumstances may reinstate competitiveness in debt markets and address the shortfall in debt capital for PPP projects.

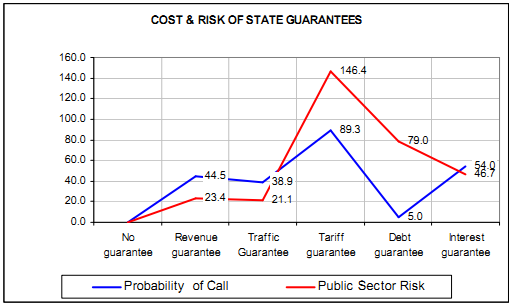

Empirical evidence suggests that the form and scope of the guarantee determine its risk and cost. Wibowo tested the different forms of contingent state support of concession toll roads in Indonesia with a view identifying the forms of guarantee that offer the best risk-return payoff to the state.100 The study values the effective state put options using stochastic probability measures and discounted cash flow valuation with a view to identifying the forms of guarantee that reduced most risk for the concessionaire at least cost to the state. Using a standard probability ranking index, the lowest state risk exposures were for debt guarantees followed by guarantees of traffic and revenues. Nevertheless, whilst the state guarantee for debt had a low probability of being called (the lowest value of the group), it can be costly if it is called (second highest) (See Diagram 5).

Diagram 5

The Wibowo study only measures headline risk which does not take into account risk mitigation and management planning that can reduce the impact of both risk and uncertainty in long-term infrastructure contracts. State guarantees may also be conditional, subject to limited liability caps or reducing over the life of the project. These qualifications may reduce state liability with this method of project support.

Infrastructure is generally financed on the basis of limited recourse debt. The lender's security interest is limited to the assets and contracts that are being financed. In Australia, there has been a preference for medium-term syndicated bank debt which is refinanced periodically during the early stage of the project following periodic revaluation. 101 This exposes SPV's to periodic refinancing, interest rate and currency risks not encountered with traditional project finance. Project lenders have a loan agreement with the SPV and possess certain "step-in" rights in the event of borrower default including breach of debt servicing obligations.

Table 4 COST & RISK OF STATE GUARANTEES

|

No guarantee |

Probability of Call |

Private Sector Risk |

Public Sector Risk |

|

Revenue guarantee |

0.0 |

17.9 |

0.0 |

|

Traffic Guarantee |

44.5 |

9.3 |

23.4 |

|

Tariff guarantee |

38.9 |

13.8 |

21.1 |

|

Debt guarantee |

5.0 |

16.5 |

79.0 |

|

Interest guarantee |

54.0 |

15.3 |

46.7 |

NOTE Assumes full guarantees only without "shading in" variations Introduced by caps and collars on liability exposure or negotiation of conditions precedent.

SOURCE Wibowo 2004.

Most of Australia's infrastructure service providers and nearly all major PPP projects are rated by credit agencies. For new projects, this takes place at the time of raising initial capital and on a continuing basis. Most of Australia's recent listed PPP projects were rated investment grade which corresponds with Standard and Poor's BBB rating level.102 Credit ratings are a proxy for default risk and a correlation exists between the rating, credit spreads and the rate of default.103 The credit default rates for corporate credit ratings is set out at Table 5.

of Australia's PPP projects have underperformed against expectation and resulted in the exercise of step-in rights or surrender of franchise. They include La Trobe Regional Hospital, Sydney's Cross-City Tunnel and the Sydney Airport Railway project. In all each case, the principal investment loss was carried by equity investors. In the case of the Cross-City Tunnel, the asset was sold and refinanced by new concessionaires with another lender. In land transport projects, the defaults were primarily a result of overestimation of patronage although in both the land transport projects, other factors were also evident.104

Table 5 Credit Default Rates

Credit Rating | Default Rate % | Credit Spread bp pa |

AAA | <1.0 | <362 |

AA | <1.0 | >362 |

A | 1 | 425 |

BBB | 3.4 | 670 |

BB | 9.7 | 880 |

B | 20.3 | 1,500 |

CC | 44.6 | 3,370 |

SOURCE Standard and Poor's 2008

_________________________________________________________________________

88 These risks may concern site conditions, design and contractual disputes, industrial relations, access to networks, patronage, operations and life cycle cost risk (Partnerships Victoria 2001a).

89 Standard and Poor's 2002, 2003; Flyvbjerg, Skamris Holm and Buhl 2006.

90 The Airport Link rail project in Sydney achieved around 25% of forecast patronage in its sixth year of operation. The Brisbane Airtrain also experienced patronage well below the levels forecast for its first 5 years of operation.

91 Greer 2009.

92 In Queensland, this is Accounting Policy Guideline (APG) 9 and Australian Accounting Standard AASB137, Provisions, Contingent Liabilities and Contingent Assets.

93 AASB137, Appendix A, p. 30; Queensland Treasury 2005, p. 86.

94 Australian Accounting Standards Board 2008.

95 AASB 2008.

96 Webb 2002; English and Guthrie 2002.

97 The Loans Council is formally a Commonwealth, State and Territory Ministerial Council operating under the Financial Agreement between the Commonwealth, State and Territories, a schedule to the Financial Agreement Act 1994; Australian Accounting Standards Board 2007, Whole of Government and General Government Sector Financial Reporting, AASB1049, October.

98 Commonwealth of Australia 2008.

99 Public debt is one of the indicators taken into account with sovereign credit ratings (Standard and Poor's 2005, 2007).

100 Wibowo 2004.

101 Tapper and Regan 2008.

102 Standard and Poor's 2005 , 2006, 2007.

103 Standard and Poor's 2009.

104 Auditor-General of NSW 2006.