Transport

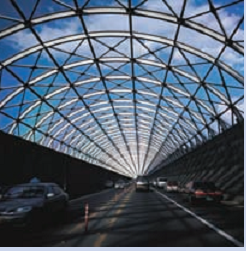

Public-private partnerships have played an increasingly central role in answering the pressing need for new and well-maintained roads, tunnels, bridges, airports, ships, railways, and other forms of transportation. Internationally, transportation has been far and away the largest area of PPP investment.41

Several factors make most transportation infrastructure ideal for PPPs. First, the strong emphasis on the role of cost and efficiency helps to align private and public interests. Second, the growing (but by no means universal) public acceptance in many countries of associated user fees for assets such as roads and bridges makes private financing easier in this sector than others where the government must pay the private sector a fee for providing the service. The ability to limit participation to paying customers, in the form of train tickets or bridge tolls, ensures a revenue stream that can offset all or some of the cost of provision in many countries-a format readily understood by the private sector. Third, the scale and long-term nature of these projects are well served by PPPs.

Australia's transport sector was one of the first to use PPPs to deliver infrastructure, with the states of Victoria and New South Wales pioneering public-private road partnerships. Sydney now has the world's largest network of urban toll roads. As of October 2005, approximately 25 percent of all contracted PPP projects within Australia were related to the transport sector.42

Spain and Italy also have considerable experience using PPPs for roads. Most of the existing toll highways in Spain were put out to concession in the 1960s.43 Today, the government hopes to use PPPs to fund one-third ($113 billion) of the estimated investment needed in road and rail between 2006 and 2020.44 Similarly, the transportation sector makes up the bulk of PPPs in Italy (with a value of $11.4 billion).45

In the United States, a $21 billion investment in 43 major highway facilities has been undertaken using various public-private partnership models over the last dozen years. California, Florida, Texas and Virginia are leaders in this field, accounting for 50 percent of the total dollar volume ($10.6 billion) through 18 major highway PPP projects.46

|

| Table 1. PPP Sector Opportunities |

| |||

|

| Sector | Leading Practitioners | Main PPP Models Employed | Challenges |

|

|

| Transport

| Australia, Canada, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, New Zealand, Spain, UK, US | DBOM, BOOT, Divestiture | • Demand uncertainty • Supply market constraints • Opposition to tolls • Transporation network impacts • Competing facilities |

|

|

| Water, wastewater, and waste

| Australia, France, Ireland, UK, US, Canada | DB, DBO, BOOT, Divestiture | • Upgrading costs and flexibility • Uncertainty about technology and need for innovation • High procurement costs for small-scale projects • Political sensitivity around privatization concerns |

|

|

| Education

| Australia, Netherlands, UK, Ireland | DB, DBO, DBOM, BOOT, DBFO/M, integrator | • High cost due to uncertainty about alternative revenue streams • High procurement costs for small projects • Uncertainty about future demographic or policy changes |

|

|

| Housing/urban regeneration

| Netherlands, UK, Ireland | DBFM, joint venture | • Refurbishment costs and flexibility • Uncertainty about future demand and revenue steams • Joint delivery |

|

|

| Hospitals

| Australia, Canada, Portugal, South Africa, UK | BOO, BOOT, integrator | • Uncertainty about future public health care needs • High transaction costs in small-scale projects • Political sensitivity around privatization concerns |

|

|

| Defense

| Australia, Germany, UK, US | DBOM, BOO, BOOT, alliance, joint venture | • Uncertainty about future defense needs • Rate of technological change • High upfront costs in small-scale projects • Securing value for money in noncompetitive situations |

|

|

| Prisons

| Australia, France, Germany, UK, US | DB, DBO, BOO, management contract | • Political sensitivity • Public purpose issues • Specifying outcomes |

|

| Transportation PPPs:Challenges and Solutions |

| Challenges |

| Cost containment. This is hugely important given the generally high capital value of transport PPPs. |

| Competitive markets. In developing PPP markets, only a small group of companies may have the financial capability to deliver cost-effective PPP projects. The range of complex financial arrangements required for transport PPPs and the relative lack of expertise in such matters also narrow the scope of potential partners. |

| Demand forecasting. Accurate traffic demand forecasting can be tricky for new roads and other forms of transport, complicating financing arrangements that often are predicated on a certain level of toll revenues. |

| Solutions |

| Because the transportation sector is the most advanced in the use of PPPs, several solutions to these challenges have already been tested. For example, "shadow tolling" and availability based payments have been used in situations where demand uncertainty about road use makes pulling a financing package together difficult. The public sector pays "tolls" to the private partner based on the availability of the asset to users and on service levels, such as the condition of the roads, thus transferring the demand risk to the public sector and allowing the project to go forward under conditions of uncertainty.

|

| Port of Miami Tunnel: |

| Availability Payments |

| The Port of Miami is actually an island off the coast of Florida, currently connected with the city of Miami by a highway that goes through the central downtown area. The port generates a tremendous amount of cargo and passenger traffic, causing substantial congestion in downtown Miami. The state Department of Transportation has proposed a $1 billion tunnel to bypass the downtown area and allow highway traffic direct access to the port. |

| Because it lacked experience in either designing or constructing tunnels, as well as the desire to build such expertise internally, the state transport department initially decided on a designbuild partnership. Quick construction was essential because of public concern regarding the congestion, so choosing a private firm made sense. The department also decided against imposing tolls on the use of the tunnel because it wanted to encourage users of the port to use the tunnel. Instead, the state would indirectly capture user fees through container and passenger fees on docking ships. Additional funds would come from Dade County and the city of Miami in return for the congestion relief. |

| After determining the sources of revenue, the transport agency considered a large revenue bond, but decided against it because it would be tied to a 30-year repayment schedule. The agency finally settled on a DBFO/M for the tunnel proposal, with the private financing being repaid by the agency through revenue raised on the container and passenger fees. The payments would be tied to the availability of the tunnel (meaning its being open for operation and available to users) in addition to quality measures-but not to the specific number of vehicles passing through. The payments would also rise if traffic exceeded certain threshold levels to compensate the private partner for increased maintenance costs. |

| The private partner in this arrangement does not bear any risk for demand management: if traffic falls below projections, the private partner would still receive the same payment, assuming it met quality measures. The state agency decided to retain the demand risk because it felt it had better control of that risk. The agency was relatively confident about the continued longterm growth of both the city and the port and did not believe that demand risk would pose a significant problem. |

| The Port of Miami project illustrates some interesting options. The use of availability payments could sidestep some of the political concerns regarding tolls. Just as important, the use of container and passenger fees in lieu of tolls could potentially streamline both traffic and collection issues. |