3.1 Conceptual framework

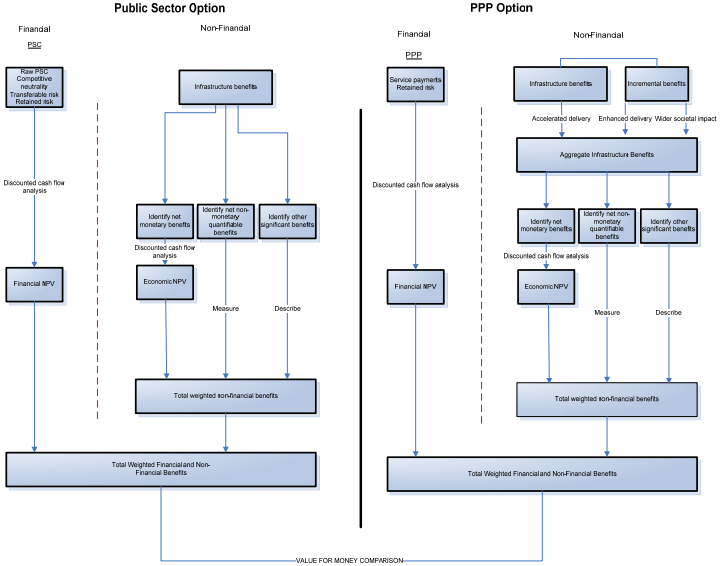

Figure 1 presents an overview of the updated VfM framework which would seek to include the analysis of NFBs in the VfM comparison.

Both the public and PPP options are composed of a financial and non-financial component:

∙ The financial costs and benefits represent cash outflows/inflows (risk-adjusted) that usually fall on the public sector decision-maker;

∙ The non-financial component represents socio-economic costs and benefits that are delivered to service users and wider society.

As we have seen, the NFBs associated with PPPs potentially include benefits associated with Accelerated Delivery, Enhanced Delivery and Wider Societal Impact. The total NFBs associated with the PPP option are captured under "Aggregate Infrastructure Benefits" in Figure 1.

As indicated in Box 4, some benefits may be valued in monetary terms. Where this is not possible they should be quantified, or where quantification is not possible, identified with the greatest possible precision.

In general, benefits that should be included in the matrix for appraisal will vary by project type and sector. Clearly, as projects grow in size and complexity, additional resources may be justifiably included in the appraisal, but should be proportionate to the importance of the project at hand. Moreover, benefits should cover only those factors that are affected by the project under consideration and be estimated over the lifetime of the asset.

Within this framework, the benefits appraisal results should then be presented alongside the financial cost comparison in the appraisal to assess the overall VfM of an option.

Figure 1 - A revised VfM framework

Box 4 - Benefit measurement

Benefits that can be quantified and valued Where possible the value of benefits should be imputed from real or estimated prices associated with them. For instance, if a benefit is traded on the market, then this can be used to estimate its value, though suitable allowances may need to be made for taxes and subsidies. Where there is no market price available, then various methods have been developed to infer the value of a benefit.25 The revealed preference approach infers a price from consumer behaviour. For example, the relationship between house prices and levels of environmental amenity, such as peace and quiet, may be analysed in order to assign a monetary value to the environmental benefit. Another approach is based on estimating willingness to pay by imputing a price from questionnaires and interviews. For example, interviewees can be asked how much they are willing to pay for improving the quality of services, time savings, etc. or how much they are willing to pay to avoid undesirable outcomes. MAPPP's analysis (see Box 2) represents an interesting, and potentially valuable, variant of this approach. Sensitivity analyses should be conducted to test how sensitive benefits are to changes in key assumptions. Benefits that can be quantified Some benefits may be quantified but not expressed in monetary terms. For example, improved educational attainment may be expressed in terms of grades obtained or numbers of years in schooling, but the value of this is difficult to assess. Similarly, user satisfaction can be difficult to monetise, though one can provide a scale for comparing satisfaction levels. Environmental impact in particular can be difficult to value. Where possible it should be expressed in established physical units but not in monetary terms should be measured in their respective units.26 By established or accepted physical measures we refer to those that have been thoroughly tested, are sustained by empirical evidence, are consistently applied across various investment projects within that sector and about which there is a high degree of consensus. When alternative physical measures are available one must select that which is most appropriate for the particular characteristics of the impact in question and correlates well with individuals' perceptions and satisfaction/ dissatisfaction ratings. Again, where appropriate sensitivity analysis should be conducted to estimate the vulnerability of benefits to key assumptions. Other benefits In some instances, impacts cannot be monetised or quantified but can only be identified. Examples of this include the aesthetic improvement to local area, consistency of proposal with government policy, replicability of innovation in future projects. In this case, they should be described in detail so that one can make an informed decision. |

___________________________________________________________________________

25 See HM Treasury, Greenbook

26 See Department of Treasury and Finance, Investment Evaluation: Policy and Guidelines (1996).