B. Administrative Mechanism and Coordination

The administrative mechanism of PPP project implementation depends on the system of government and the overall administrative structure, and the legal regime concerning PPPs. As these elements vary from one country to another, the administrative mechanism also varies from one country to another. Generally, the sectoral agencies at the national and provincial levels (in a federal structure) initiate and implement most of the PPP projects. However, in many countries, the Philippines for example, local level governments such as city governments are also allowed to undertake PPP projects.

Depending on the political and administrative systems in a country, the implementation of PPP projects may require the involvement of several public authorities at various levels of government. For example, the regulatory authority for a sector concerned may rest with a public authority at a level of government different from the one that is responsible for providing a particular service. Sometimes, the regulatory and operational functions are combined in one authority. This arrangement is usually common in the early years of private participation in a sector. The authority to award PPP contracts and approve contract agreements is generally centralized in a separate public authority. This may be a special body for this purpose and is usually at the ministerial or council of ministers level.

The legal instruments and/or government rules and guidelines define how the sectoral agencies and local governments may initiate, develop, submit for approval of the national/provincial government, procure, negotiate and make deal with the private sector, and finally implement a project. These legal instruments may also define the authority and responsibilities concerning PPPs at different levels or tiers of government.

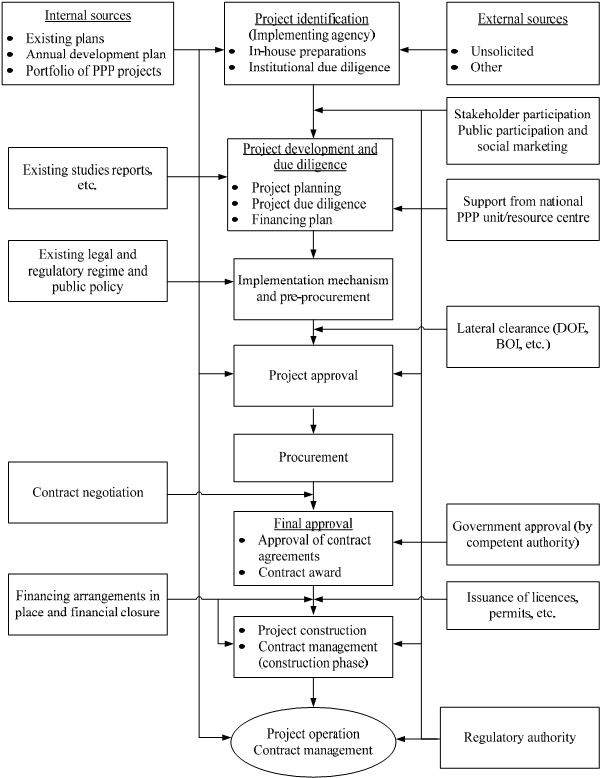

| Figure 1 shows the steps that are generally considered in a PPP project implementation process. More details on tasks at various stages of project development and implementation are provided in table 1. Clear definitions and procedures of various tasks and administrative approval from competent authorities at different stages of project implementation process are necessary in running a successful PPP programme. Streamlined administrative procedures reduce uncertainties at different stages of project development and approval and help to reduce the transaction cost7 of a PPP project. Annex I provides an example of the defined PPP project implementation process and tasks at each stage in the state of Victoria in Australia. | Steps in PPP project development and implementation |

|

|

| Developing a PPP project is a complex task requiring skills of a diverse nature many of which are not normally required for traditional public sector projects. The success of PPP projects depends on a strong public sector which has the ability to identify, develop, negotiate, procure, and manage suitable projects through a transparent process. However, the knowledge and the necessary skills that are required in development, financing and management of PPP projects are often lacking in the public sector. | Why PPP units may be necessary |

|

|

One means of developing the knowledge and skills has been the creation within governments of dedicated Public-Private Partnership Units or launching of special PPP programmes with similar objectives. Such units or programmes have been established in many countries in Asia and Europe and they are structuring more and more successful projects.

Figure 1. Steps in the PPP project implementation process

| Notes: | DOE = Department of Environment; BOI = Board of Investment. |

Table 1. Stages in PPP project development and implementation

1. Identification of private sector/PPP projects

1A. Project identification

1B. In-house preparatory arrangements

• Conceptual project structure

• Institutional due diligence (legal and regulatory framework, government policy, involvement of other departments, in-house capacity, etc.)

• Project implementation strategy

• Setting of project committee(s)

Government approval (e.g. by a special body established for PPPs)

Government approval (e.g. by a special body established for PPPs)

1C. Appointment of transaction advisor (if needed)

• Terms of reference

• Appointment

Government approval

2. Project development and due diligence

• Project planning and feasibility

• Risk analysis and risk management matrix

• Business model

• Value for money

• Government support

• Financing

• Service and output specifications

• Basic terms of contract

• Independent credit rating of the project (when possible)

• Preliminary financing plan

Government approval (Special body, concerned ministries, central bank, etc.)

Government approval (Special body, concerned ministries, central bank, etc.)

• Financing plan

3. Implementation arrangement and pre-procurement

• Implementation arrangement

• Bidding documents

• Draft contract

• Special issues (land acquisition, foreign exchange, investment promotion, etc.)

• Bid evaluation criteria, committees

Government approval (Special body, legal office, Ministry of Law, etc.)

Government approval (Special body, legal office, Ministry of Law, etc.)

4. Procurement

• Interest of the private sector

• Pre-qualification of bidders

• RFP - finalization of service and output specifications

• Final tender

• Bid evaluation and selection

Government approval (Special body, cabinet, etc.)

Government approval (Special body, cabinet, etc.)

5. Contract award and management

• Contract award, negotiation and signing; and financial close

• Service delivery management

• Contract compliance

• Relationship management

• Renegotiation (when needed)

Government approval of renegotiation terms (Special body, cabinet, etc.)

Government approval of renegotiation terms (Special body, cabinet, etc.)

6. Dispute resolution

• Establishment of a process and a dispute resolution team

Government approval (when needed by defined bodies)

Government approval (when needed by defined bodies)

| Note: | Mention of government approval and the activities shown at any stage are only indicative. The actual stages of government approval and activities undertaken in any stage vary from one country to another. |

| The administrative status of PPP units, however, varies from one country to another. For instance, it may be a government, semi- government, autonomous or even a quasi-private entity. The role and function of such units also greatly vary from one country to another. While in some countries these units have a very strong role and wide range of functions from project development to project approval (as in the Philippines, Gujarat in India, and the U.K.), in other countries they have advisory role with limited functions (the Netherlands and Italy, for example). See Box 3 for more details on structure and functions of the BOT Centre in the Philippines as an example of a PPP unit. | Structure and functions of PPP units |

|

|

| Box 3. The BOT Centre, Philippines Private sector participation is a key strategy of the Government of the Philippines. The Built-Operate-Transfer (BOT) Law of 1991 spells out the policy and regulatory framework for private sector participation in infrastructure projects and other public services in the country. The BOT Centre, a government agency attached to the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), has the mandate to coordinate and monitor the implementation of the BOT Law. The Centre’s main function is to find financial, technical, institutional and contractual solutions to help implementing agencies and local governments to make BOT projects work. Headed by an Executive Director, who reports directly to the Secretary of DTI, the Centre is organized in two groups: the project development group and the programme operations group. The project development group is composed of four sectoral divisions (transport, power and environment, information technology, social infrastructure and special concerns), and the programme operations group is composed of three divisions (programme monitoring and management information, marketing and resource mobilization, administration and finance). The BOT Centre prepares and periodically reviews and updates the screening guidelines for projects applying for project funding under the project development facility, prepares the terms of reference for technical assistance to implementing agencies, reviews and moves to amend the Implementing Rules and Regulations for PSP and assists government agencies in expediting the implementation of private projects through facilitation and problem-solving interventions and monitoring of private activities/projects. As at 30 June 2006, the total value of completed PPP projects facilitated by the center was as follows: transport (8 projects), US$ 2,654 million; power sector (23 projects), US$ 7,705 million; information technology (3 projects), US$ 143 million; water (5 projects), 7,839 million; property development (5 projects), US$ 33 million; others (3 projects), US$ 416 million. Besides, there were also number projects for which concessions have been awarded and were under construction, and projects which were in different stages of the approval process. Source: Communication with the BOT Center (August 2006), and Kintanar et al 2003. |

Another important issue in project implementation is administrative coordination. Generally, multiple agencies are involved in project implementation. The issuance of licences and permits may also need action of many government agencies, often at different levels of government. An institutional mechanism may be required to be established for the coordination of actions by the concerned agencies involved in project implementation as well as for issuing of necessary approvals, licences, permits or authorizations in accordance with the legal and regulatory provisions. The implementing agency can identify all such agencies and authorities that would be involved in the implementation process and in issuing the licences and permits, and establish coordination/liaise mechanism at the outset to facilitate the required approvals and issuance of licences and permits in a timely manner.

| MAJOR ISSUES CONCERNING INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENT… • It is necessary to reduce the level of uncertainty surrounding public-private partnership project deals to increase the confidence of investors. In many countries, the existing legal and regulatory environment may be conservative and too restrictive for undertaking PPPs. Governments have considered enacting new legislations or suitably amend their existing infrastructure laws to address this issue. The legal instruments may specify, among other things, the general conditions for PPP models, provision of financial and other incentives, and details of project development and implementation arrangements. • Clear definitions, responsibilities and timeframe for various tasks and a transparent rule-based administrative process by which PPP projects are developed, approved and procured by governments are necessary in running a successful PPP programme. Streamlined administrative procedures reduce uncertainties in project development and approval, and also reduce the transaction costs in project development. • The knowledge and the skills that are required in PPP project development and implementation are often lacking in the public sector. One means of developing the knowledge and skills has been the creation within governments of dedicated Public- Private Partnership Units or launching of special PPP programmes with similar objectives. Such units have been created and programmes launched in many countries of the world. |

___________________________________________________________________________

7 The development of a PPP project requires firms and governments to prepare and evaluate proposals, develop contract and bidding documents, conduct bidding and negotiate deals, and arrange funding. The costs incurred in these processes are called transaction costs, which include staff costs, placement fees and other financing costs, and advisory fees for investment bankers, lawyers, and consultants. Transaction costs may range from 1 to 2 percent to well over 10 per cent of the project cost. Experts suggest that transactions cost vary mainly with familiarity and stability of the policy and administrative environment and not so much with the size or technical characteristics of a project (See in Michael Klein et al., 1996. “Transaction costs in private infrastructure projects - are they too high?”, Public Policy for the Private Sector, Note Number 95, World Bank, Washington D.C. Available at:<http://rru.worldbank.org/Documents/PublicPolicyJournal/095klein.pdf>.)