The Elements of the Reform Process

In practice, the development of partnerships as a means to the delivery of services in municipalities occurs as a part of a larger, all-encompassing municipal reform process. Central to this discussion is the reorientation from top-down urban planning and management to effective urban governance. The concept of local governance involves a variety of local agents in the sharing of power, with municipal government having a coordinating rather than a monopolistic and controlling role.1

Yet for municipal government, the shift in policy and attitudes required to achieve good governance is not easy or natural. Apart from the development of a sound democratic basis, approaches to good governance require municipalities to reposition themselves as one of many municipal stakeholders, and to create effective participatory processes with these stakeholders. It requires municipalities to develop an accountability and transparency previously unknown to them. It requires innovative organisational, human resource and financial management. It requires municipalities to reconsider their provider role in all municipal functions, to develop a predictable environment, to consider the potential of all private and civil society stakeholders including informal stakeholders, and to reconsider delivery mechanisms. In practice, it may require strategic change, be it through networking with other municipalities or unbundling functions.

It is important to remind advocates of PPPs in specific municipal services that the key aspects attributed to effective partnerships are in fact a reflection of the principles of better governance.2 Partnership actors should not assume that accountability and transparency or strategic planning are pursued only for the good of the partnership. In most cases these are broader governance concerns, and PPPs should link into and build on existing efforts, no matter how humble.

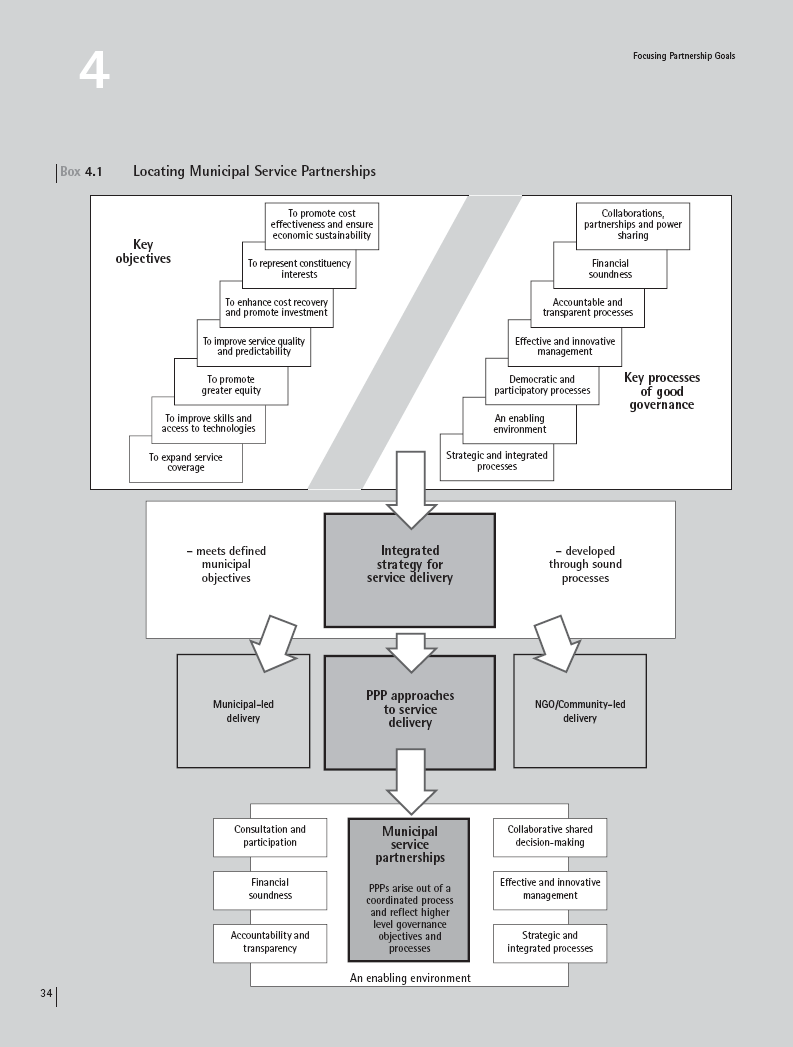

Yet the key aspects of good governance are often vital to the development of service partnerships (see Box 4.1). For instance, the formulation and sustainability of partnerships will be dependent on the commitment and mobilisation of councillors and political leaders. Immature political leadership will affect all municipal reform processes and capacity building is an important part of a municipal reform programme. Whereas partnerships can promote capacity building in some areas (e.g., to induct new councillors in PPPs), the development of capable leaders in newly democratised contexts takes time. Partnerships are put at risk when key (non-public sector) actors fail to understand the complexity and susceptibility of new councils.

The processes of democratisation are not limited to electoral democracy; they also include the development of stakeholder participation in municipal decision-making. Whereas some consultative processes are developed purely for the purpose of partnership formulation, in most cases municipalities will have already established vehicles for involving civil society and the private sector in municipal decision-making. Organisational structures may be an important part of this process: for instance, the neighbourhood committees and ward committees in Indian cities are established and legal forums for participatory decision-making. It is important that participatory processes concerning service partnerships build on such structures (addressing, of course, the known deficiencies of that structure).

Municipalities clearly experience growing pains when adopting more open participatory approaches in relation to all decisions, including private sector participation. Administrators accustomed to calling the shots must get used to facilitating rather than controlling. Engineers struggle with redefined roles that undermine their status and power as the providers of technical knowledge. Newly elected politicians must accept that winning a seat does not give them carte blanche in decision-making. All municipal actors must engage in the collaborative spirit and work with other stakeholders.

Best practice in urban management prioritises strategic planning and highlights the importance of holistic and integrated processes and solutions. Yet in the recent past, the sectoral nature of service partnerships has promoted isolated sectoral solutions, and in some cases a lack of coordination has undermined city development strategies. The strategic process must focus initially on the overall picture, and provide a framework for developing specific partnerships in functional sectors. Conversely, establishing an integrated strategy is likely to enhance the benefits to be gained from a service partnership and enable benefits to be targeted.

The strategic vision of municipal services also requires supporting institutional arrangements. Municipalities therefore establish committees, task forces and other dedicated units to coordinate their various departmental interests. If a municipality is keen to pursue partnership options, it must establish the structure with which to do so. This was the approach taken in Kathmandu in Nepal, where a high-level committee, a task force and a secretariat were established to take the private sector participation policy forward (see Box 4.2).

Establishing sound urban management also means that a municipality must address those areas in which it lacks an acceptable level of professionalism. These activities will vary from overall improvements in the technical and managerial capacity of staffing, to the formulation of procedures that promote accountability and transparency, to the introduction of information technologies to assist in administrative functions. Each of these processes affects and will be affected by the formulation and implementation of partnerships. At the same time, the process of establishing a service partnership is in itself characteristic of a more professional organisation, and a willingness to accept change, challenge the status quo and promote better ways of fulfilling municipal obligations. Important aspects of this include the development of an enabling environment and effective financial management.

This reform process is not easy. The natural tendency of governments to resist change, the lack of skills and access to capacity building, the engrained and sometimes corrupt practices of dysfunctional municipalities, the resistance to transparency, and the fear of technology and human resource changes all emphasise the need for massive attitudinal change. The emergence of service partnerships in this context can be both problematic and supportive. 'Learning by doing' is an important capacity building method, and municipal officials may well be convinced by seeing how the private sector works, and the tangible improvements in municipal services. However, the slow rate of change to a more transparent and accountable organisation and the inertia of a municipality can frustrate partnership development. These aspects of organisational capacity building are discussed further in Chapter 12.

Given the interconnected nature of partnership approaches and current attitudes towards governance and management, it is essential that municipalities understand how partnerships can underpin good governance and how good governance can support partnerships.

Does the development of PPPs support good governance? While the answer given is often an unambiguous 'yes', when examined closely the answer is more likely to be that certain types of partnerships support the processes of good governance, while those that are exploitative or non-consensual clearly do not. To this end, municipalities need to know that they can and should make changes to these partnerships, introduce participatory processes, establish a competitive environment, and ensure the involvement of all stakeholders in creating partnerships that align with their objectives. Municipalities forming new partnerships would be wise to look to those private sector partners with experience in this approach. Among other benefits, this will gradually create a demand for a private sector that is better able to work within the bounds of good governance objectives.

In order for partnerships to support broader governance initiatives, it is important that municipalities and their partners ensure that arrangements do not ignore fundamental principles of reform. This may be a tall order, but in recent years evidence has suggested that a new breed of partnerships can work within these parameters. These new partnerships encourage participatory and consultative processes, engage actors from civil society, promote transparency through awareness building and open policies, and also promote the development of solutions appropriate to a particular context. Yet this has not always been the case: many existing, more traditional PPPs are far from participatory or consultative. Many do not possess the flexibility required for good governance, and many government-sanctioned monopolies have ignored calls for greater competitiveness and transparency.

Does good governance support the development of PPPs? This chapter argues explicitly that the efforts made by urban managers towards good governance are at the foundation of PPPs, and that the development of PPPs is a reflection of these broader efforts. That is not to say that all municipalities pursuing good governance objectives will give the highest priority to private sector participation. Many prefer to pursue collaborations with NGOs and communities first, while others have started with internal reforms, or are focused on establishing more effective and accountable processes.

Box 4.1 Locating Municipal Service Partnerships |

|

Box 4.2 Municipal Policy Towards Public-Private Partnerships |

Kathmandu, Nepal |

The most significant private sector participation (PSP) activity in Nepal has developed in Kathmandu. The most recent efforts have focused on the development of a policy framework for private sector participation in the municipal (KMC) functions. Approved by the municipal board, this outlines, in explicit terms, the intention to 'attract the private sector by creating a conducive and trustful environment for their investments by ensuring the maximum facilities that can be given by KMC'. With the support of an Asian Development Bank (ADB) capacity building programme, the KMC has drawn in specialist skills to assist in policy development. It is contemplating a range of different forms of PSP and a number of priority areas. |

There are several opportunities for PPP in Kathmandu: |

• the expansion of existing urban services and additional necessary services to meet the overall development objective of KMC; • an increase in the KMC's management capacity through private sector investment for PPP projects; • the construction and management of basic facilities in health services, education, water supply, solid waste management, commercial complexes, industrial estates and other main services; and • the development of a market, a bus terminal, a modern slaughterhouse, an underground car park, mass transit along the ring road and many other similar projects. |

The priority areas and potential for private sector participation in the KMC and other locally dominated activities are significant. The KMC has identified many potential projects, some of which are already being implemented. Most of these are in the solid waste management area. Other potential activities include construction and/or operation of marketplaces, passenger bus terminals and a slaughterhouse. The priority areas for PSP and PPP activities are urban services, single-function commercial activities and integrated area-development ventures. 'Urban services' are made up of three services, although the KMC is responsible for neither water nor road maintenance. 'Single-function commercial activities' refers to business activities that in other circumstances might be government-regulated commercial private sector activities: abattoirs, passenger bus terminals and parking facilities. All these activities have great potential to recover their investment and operating costs through user fees. 'Integrated area-development ventures' include commercial complexes and industrial estates. These ventures are interesting, because the KMC does not have the resources to provide urban services directly to the area developments. Thus, the developments must build and maintain the services by themselves. Because these new 'enclaves' are self-financing, they are a natural starting point for private sector involvement. The KMC has plans to package such a venture. |

There are two types of sub-sectors: service contract sub-sectors (non-capital-investment) and investment sub-sectors (capital- intensive). A single sector, such as solid waste, can comprise both service-contract sub-sectors (street sweeping, collection of solid waste, billing and collection) and investment sub-sectors (recycling, landfill disposal, composting activities). Investment sub- sectors deserve special attention because they bring 'off-budget' funds for capital additionality. It is also challenging to arrange private sector involvement in these sub-sectors because more assurances are required to protect private sector investment. |

Criteria have been established for the selection of PPP proposals. These include financial viability, technical and engineering competency, contract and institutional management capacity and project management capacity. Basic standard operating procedures have been developed under this policy framework for PSP transactions. These include feasibility guidelines, procurement guidelines and contracting guidelines that will be made available to the interested private parties for transparent transactions. |

The following institutional arrangements have been made by KMC to facilitate the PPP projects: |

• A high-level committee consisting of representatives from all the political parties within the KMC and other professional associations like the Nepal Bar Association, the Nepal Engineering Association, the chambers of commerce and industries, and Transparency International. The main function of this committee is to formulate PSP policies and to approve the projects for implementation. • A PSP task force including all the departmental heads concerned, experts as required and members of the respective committee. The task force examines the proposal submitted by the private sector minutely and also checks the tender document according to set standards, and then recommends it to the high-level committee for consideration and approval. • A PSP secretariat, which is being established under the private secretariat and protocol office of the mayor. The function of the secretariat is to coordinate and facilitate PSP activities for smooth decision-making within the departments, the high- level committee task force and external private parties. |

Through acknowledging the importance of PSP for the overall development and upgrading of the infrastructure and services of Kathmandu, the slogan 'my pride, my legacy and my Kathmandu' will be achieved. |

Source: Kathmandu Metropolitan City, 2000 |