Do Public-Private Partnerships Currently Do Enough?

When international agencies first started promoting private sector involvement in municipal services, the inefficiency of the public sector in delivering urban services was the fundamental cause of concern. As a result, support - and publications - in the early to mid-1990s mainly focused on the benefits of private sector participation (PSP) and how it could be achieved. In this context, the delivery of services to low-income areas was part of the problem to be solved and was addressed through the development of policy, regulatory frameworks and contract provisions in relation to tariffs, expansion mandates and network upgrades. At this time, consideration was not explicitly given to the diversity of the customer base in developing countries or, more specifically, to the complex set of issues concerning delivery to the poorest households. The very shift to private sector involvement in the delivery of basic services required a fundamental reorientation and this occupied the debate in its earliest years.

Since that time, a number of factors have led to greater consideration being given to the poor in the development of public-private partnerships (PPPs) in service delivery. The primary multilateral advocate of private sector participation in these early years, the World Bank, has accrued significant experience in PPPs in a range of sectors (electricity, water and sanitation, telecommunication), and those involved in the formulation and monitoring of this process have seen the need for solutions that more effectively reach the poor. Simultaneously, and adding weight to this direction, the World Bank has itself introduced a more explicit policy focus on poverty reduction in its client countries.

Recently, therefore, many of the Bank-led discussions about private solutions to infrastructure provision for the poor have been developed by organisations and individuals already committed to private sector participation in service delivery. They bring with them a wealth of knowledge about the particulars of policy, regulations, incentives, and tariff structures, all of which are core concerns for PPPs. The approach generally adopted is to draw first on the key elements and lessons of existing contracts. The result of this investigation and the current direction of pro-poor PPPs for infrastructure is that the overall shape of the partnership is being manipulated but its basic structure remains the same. Some would argue that only the trimmings have been changed.

In relation to water and sanitation services, this approach has been taken further by two other important (and related) organisations: the Business Partners for Development1 initiative focusing on the water and sanitation sector, and the broader Water and Sanitation Program.2 Both seek to create a shift in the way the PPP works (see Boxes 6.20 and 6.21). With the cooperation of operators, the public sector, NGOs and donors, each has developed or been working with a range of pilot projects that have stretched the boundaries of standard contracts, extended actor roles and created innovative processes. Through these initiatives a number of core issues concerning the poor have been rethought, and alternative technical, financial and institutional solutions are currently being considered. In particular, the role of NGOs is being reconsidered and extended into PPPs, approaches to condominial systems are now being tested, discussions on tariff structures and subsidies are addressing impacts on the poor, and the issues surrounding expansion mandates and service standards are being explored. Each of these avenues of investigation is developed further throughout this sourcebook.

Notwithstanding the increasing interest in extending the boundaries of PPPs, to date these are isolated initiatives. Most approaches to PPPs are still based on standard models and assumptions, and these determine the limits to which PPPs can contribute to poverty issues in the urban environment. They include, for instance, the assumption that the poor obtain indirect benefits when city-wide operations are more efficiently and skilfully delivered (there is little focus on negative impacts); that PPPs are developed in single service sectors; and that PPP arrangements conform to one of the pre-established PPP contract types.

Is this enough? In the context of broader municipal responsibilities and the shift to local governance (described in Chapter 4), municipalities must ask whether the application of a standard partnership model is appropriate. Does it enable them to meet poverty reduction goals? Can they expect more? Should they strive for more? Can their objectives be met by squeezing and adapting the traditional PPP paradigm?

For those primarily focused on urban poverty reduction, one of the problems with the existing approach towards private sector participation in municipal service delivery is that it takes PPP delivery models developed in the North and applies them in the South. Without questioning the possible benefits of private sector participation or discouraging private sector investment in developing countries, it is wise to explore whether these Northern models are well constructed for the prevailing context of poverty and capacity deficiency found in municipalities in developing countries. Can the basic parameters of the partnership be focused on maximising the potential for the poor, rather than making do with what can be achieved within existing constructs? Can the scope be defined in relation to the needs of the poor rather than defining the scope in relation to a contract type?

Another cause of disquiet is that the vast range of lessons that have been learnt through decades of urban poverty projects have seemingly been cast aside in the rush towards the partnership approach. Many PPPs have been developed by economic, financial, legal and engineering experts, who are knowledgeable in the mechanics of contracts but quite inexperienced in the nature and scope of the social and institutional problems of impoverished cities in developing countries. Few have drawn on the vast knowledge that has been developed in the course of implementing decades of service delivery projects with poor communities.

In order to consider the potential of private sector participation in the delivery of services to the poor, it is helpful to stand back from current approaches, models and contract types. Rather than asking how a model contract can be adapted to suit the poor, this chapter focuses on how service delivery processes can be constructed to best respond to the needs of the poor. In looking towards the private sector, it suggests that municipalities should be exploring strategic change more fully and promoting deliberate contributions to existing poverty reduction objectives. It requires forward planning and action to ensure that the foundations of the partnership framework are more appropriately defined, both in themselves and in relation to other poverty-focused activities. This discussion, therefore, considers how a municipality might go about developing a poverty strategy for a partnership, and highlights the key ingredients of that strategy. Drawing on the lessons of poverty reduction processes and policy, it proposes ways in which municipalities can integrate private sector participation in a livelihoods approach to poverty reduction.

Ideally, a framework for focusing a service partnership on the poor grows out of a broader municipal poverty strategy and participatory initiative. If municipalities do not have an established poverty strategy, steps can be taken to locate partnerships within the broader agenda of poverty and poverty reduction by:

• developing better understanding of the characteristics of poverty;

• defining the needs and objectives of the poor in relation to services;

• identifying the key processes that underlie a partnership involving the poor;

• identifying the key issues of concern to local communities and households; and

• identifying the key stakeholders and assets that support existing livelihoods.

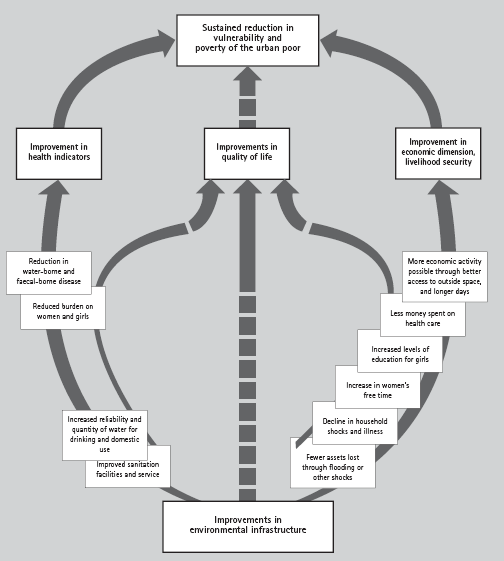

Box 5.1 Potential Impacts of Infrastructure Improvements |

|

Sources: Adapted from Amis, 2001; Plummer, 2000b