A Poverty-focused Partnership

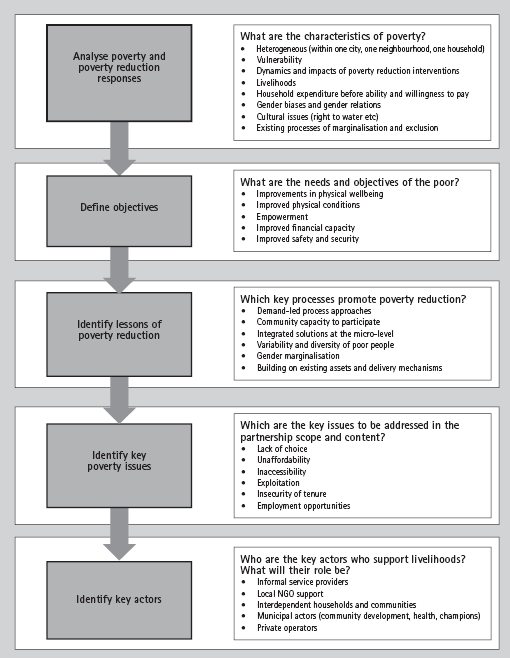

A poverty-focused partnership is thus an integral part of a broader strategic approach to poverty reduction. If possible, it should originate from an overall poverty strategy and be developed to link closely with other parallel actions. This means that municipalities must facilitate the coordination necessary to achieve this approach.13 The first responsibility of the municipality is to define the needs and objectives of the poor. A range of processes, actors and actions (illustrated in Box 5.6) are central to poverty-focused partnerships.

Perhaps the most fundamental shift requires all partners to recognise that people, rather than the service, are at the centre of the initiative. Any one service or service partnership is just a portion of an overall response to poverty, and must be envisaged as a contribution that needs to be coordinated. A single sector partnership is never a holistic response: it always requires interaction with other parts. It is impossible to avoid the fact that water supply or any other service is just one dimension of improved physical wellbeing, and improved physical wellbeing is just one livelihood outcome. Benefits will be maximised if service delivery initiatives are undertaken in relation to other livelihood outcomes.

It is also necessary to ensure that any potential negative impacts on livelihoods are identified at the outset, and that mechanisms are built into the partnership framework to mitigate these effects. For instance, an ill-conceived partnership approach can affect vulnerable groups who cannot afford the service. Tenants might have to suffer higher household expenditures even though they have not been party to the decision-making. Women might have to reprioritise household finances to make payments; informal service providers (such as rag-pickers and water-sellers) may lose their livelihoods.

Accordingly, an important corollary to the approach proposed here is the need for skilled urban management - management practices that bring together very different actors, like the poor and the private sector, and emphasise the importance of integrated and strategic approaches to urban management and city development. This is not about the private sector role so much as the strategy and construction of the approach, and the capacity of the municipal or public sector body to assemble an arrangement that has a strategic intention and the capability of addressing the needs of the poor.

A second important corollary is that the donor sector, so active in the field of PPPs, must promote greater convergence of the approaches they advocate. If PPPs are to become effective in meeting the needs of the poor, they must be linked to the livelihood responses to poverty.

A third important corollary is that the private sector needs to build capacity. Despite the confidence of some international private operators, their capacity to work with the poor is often quite limited. Greater competency and new attitudes in the private sector will make for more sensitive partners, better able to grasp and work towards poverty reduction goals. In order to sit at the table with other partners working directly with the poor, the private sector requires more skills, many of which can be learnt by exploring the lessons of poverty reduction.

The implementation of a new approach to PPPs will not always be easy. As this book promotes a revised approach to PPPs, it is essential to confront constraints to such changes and to consider how any change might be achieved. Accordingly, for a municipality to succeed in bringing about a focused partnership arrangement:

• the approach and methodology must be realistic. It is necessary for advocates and implementers to acknowledge the vast differences that lie between policy formulation and the reality of bringing together public sector constraints and private sector interests.

• The framework must be open, inclusive and comprehensive, so that all potential avenues of exploration are represented even if they seem overly ambitious at the outset.

Introducing change can be remarkably straightforward when the will is in place, but it also requires capacity. What can seem radical in one context can be seen as a simple practical change in another. The key objective is to bring about a shift in approach - in arrangements, processes and actors - that will most effectively meet the livelihood outcomes defined by the poor. The concept of appropriateness is central to this end. A solution that has a sound basis and is allowed to evolve is more likely to bring about the required result than a solution that is inappropriately imposed.

Box 5.6 A Strategic Approach to Focusing Partnerships on the Poor |

|