□ The characteristics of municipalities

Like national and provincial/state levels of government, municipalities display a number of common and distinguishing characteristics.1 In democratic contexts, the primary interest of the elected leaders is political; councils are ultimately controlled by voters, and by higher political bodies. The level of political control is convincingly illustrated in South Africa where, despite apparent autonomy at the local level of government, the decision-making of elected officials at the municipal level is often determined by national-level political mandates.

Often, where local level democracy is less mature, the interests of the municipality are still determined by the executive arm, and are often bureaucratic. A municipality might be concerned with maintaining the status quo and resisting any change likely to harm existing status and hierarchies. Many contexts demonstrate how these political and administrative interests conflict, and the impacts of a resistant municipal executive on the implementation of new or challenging policies. Municipal administrators' primary concern is not the electorate, but higher levels of management whose concerns are often self-reinforcing.

In theory, municipalities obtain their power through legislative, regulatory and enforcement frameworks, and their authority to tax. However, under-resourced local governments, often secure their power through their roles as providers and patrons, and ultimately through the control they have over the allocation of municipal resources. This is particularly relevant in relation to municipal services such as water supply, sanitation and solid waste disposal, as municipal officials often have the ability to determine who gets the service, when they get it, and how much they get. The voting power of the poor does not always bring about a better outcome if politicians exclude marginalised groups or fail to act sincerely on their behalf.

Municipalities bring their important rule-making capacity to partnerships. However, they usually have many established procedures (or rules) to address situations that are very different from those with partnership strategies. One of the great concerns of constituents is that procedures can also fuel a lack of transparency. Some argue that overly bureaucratic procedures have masked the fact that decades of officials have obtained personal rewards from dubious decision-making. Moreover, dependence on historic and unnecessary procedures is also a primary reason for failure in partnerships and inefficiency. It is not the existence of rules that is in question, but the need to ensure that the rules and procedures by which a municipality functions are changed to create a partnership-supportive environment.

In particular, building partnerships requires a different approach than the usual one to rule-making, with a fully predetermined procedural framework that defines the relationships between actors. While municipalities have a critical role in bringing their rule-making capacity to develop a partnership-supportive framework, much of the framework evolves as the partnerships evolve.

Democratically elected municipalities are also concerned with very different timeframes than are potential private sector or civil society partners. Their interest in political power means that they make decisions according to a timeframe determined by elections.2 Service delivery programmes are often lengthy, and private sector partners look for contract durations commensurate with risk and investment. Yet the election timeframe can be quite short. In some states in India, for instance, mayors are elected on an annual basis, and councillors are elected every three years. This forces politicians to focus on short-term, visible results each and every year, often abandoning strategic plans that lead to sustainable long-term improvement. In relation to partnerships, the effects of such short-term thinking on long-term contracts can be detrimental to implementation processes.3 In order to combat this effect, it is critical for the partnership process to acknowledge this concern, and produce short-term results that can also be achieved within an election cycle.

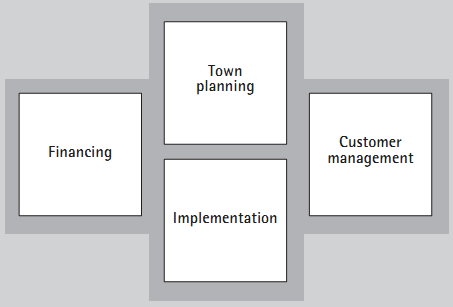

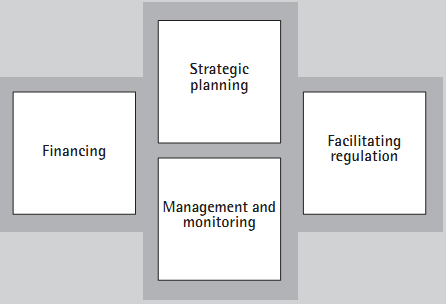

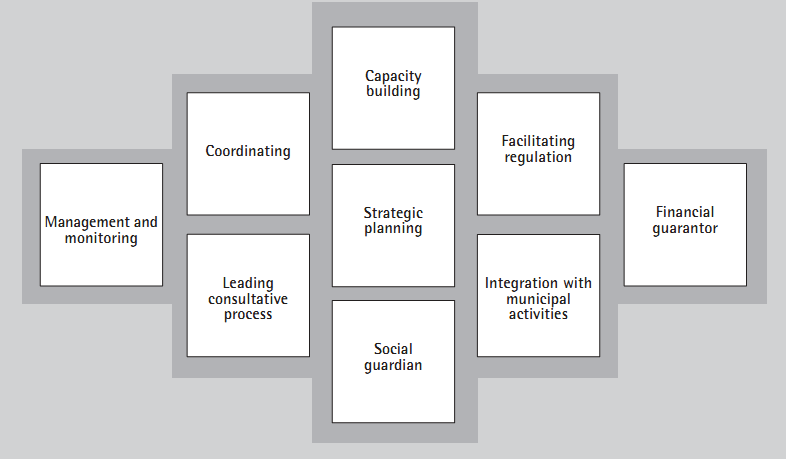

| Box 6.2 Municipal Roles in Service Partnerships | |

| (a) Municipality as provider: the traditional cluster of roles

(b) The municipal partner in a standard PPP: an amended cluster of roles

(c) Municipal roles in a focused partnership: an expanded cluster of roles

| |