□ International donors and funding agencies

International donors frequently play a key role in driving partnerships involving the private sector. Donor interest in partnerships for the delivery of infrastructure and services has certainly increased significantly over recent years, and the focus has settled on, inter alia, water and sanitation services and solid waste management. Support for partnership formation comes through:

• sectoral reform programmes, focused on creating an enabling or encouraging framework for private sector participation (through policy development and regulatory frameworks);

• private sector development programmes;

• infrastructure development; and

• municipal reform and decentralisation processes.

These international development programmes are created by agencies that are extensions of governments, in development terms. Notwithstanding the internal agendas of bilateral donors, donor interests in partnership formation may be driven by their interest in:

• promoting the role of the private sector in economic development and reducing the role of the state;

• mobilising private sector investment in the context of decreasing aid flows;

• creating a more efficient, predictable and conducive environment of aid funding and technical assistance;

• promoting institutional change in key sectors;

• promoting private sector participation in service delivery to the poor; and

• promoting efficient, equitable development.

Over the past decade, a number of agencies - the World Bank in particular - have provided direct assistance in the formulation of partnerships, and have made their own funding conditional upon private sector involvement (see Box 7.12 on Cartagena). This direct action has been supported by extensive policy formulation and analysis, and research into the key financial and economic aspects of existing transactions. A number of service sectors, including energy, water and sanitation and solid waste, have produced toolkits to provide guidance on basic issues and processes.18

More recently, however, donors have begun to merge their interest in private sector development with poverty reduction mandates. The World Bank and the Water and Sanitation Programme (WSP) have led this process through a number of global initiatives, conferences and workshops (see Box 6.19 for a description of the work of Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility).19 In the water and sanitation sector, WSP will soon publish guidelines for the development of pro-poor transactions. Donor activity is by no means limited to these examples. The UNDP PPPs for the Urban Environment (PPPUE) initiative promotes local skill development through a global learning network, and local government capacity building in three selected countries (Nepal, Namibia and Uganda).

In many of the most innovative partnerships that have tackled delivery in poor areas, donors have played a central role. Indeed, the importance of the donor as a fourth partner in public-private-civil society initiatives should not be underestimated. It raises questions of sustainability as reliance on the technical assistance takes hold, and replicability as the donor performs key social and institutional roles.

In El Alto, for instance, WSP and the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) have been involved in influencing the agenda from the outset (see Box 6.20). WSP objectives are primarily concerned with community capacity building and developing an approach for replication. To this end they have worked with the operator Aguas del Illimani to develop a condominial sewerage approach and then to institutionalise the lessons learnt. WSP employed three or four technical staff. While the project is currently learning from early decisions, the pilot has provided a model of integrated, participatory planning and implementation, empowered communities and introduced alternative technologies.

The role of donors in partnership development includes:

• provision of funds for technical assistance;

• gap-filling, where the competencies of the actors do not correspond with project objectives;

• general guidance on options, particularly in relation to poor areas;

• definition and dissemination of best practice; and

• facilitation of new initiatives as a part of broader sectoral reform.

However, with the exception of the pilot work of the Business Partners in Development (BPD) Water and Sanitation Cluster see (Box 6.21), WSP and some work by the Inter-American Development Foundation, there are few initiatives in which donors have actively pursued the potential of combining the public, private and civil sectors. The agenda of many donors clearly promotes PPPs, but in the past has fallen short of addressing poverty issues or promoting a place in the partnerships for civil society. This is an emerging area of interest.

| Box 6.21 Business Partners for Development | |

| Sustainable development is a global imperative, and strategic partnerships involving business, government and civil society may represent a successful new model for the development of communities around the world. Business Partners for Development (BPD) is an informal network of partners who seek to demonstrate that partnerships among these three sectors can achieve more at the local level than any of the groups acting individually. Among the three groups, perspectives and motivations vary widely, however, and reaching consensus often proves difficult. Different work processes, methods of communication and approaches to decision-making are common obstacles. But when these tri-sector partnerships succeed, communities benefit, governments serve more effectively, and private enterprise profits. The result is a win-win-win situation, which is the ultimate aim of BPD and its divisions, or 'clusters'. One of four sector clusters within the BPD framework, the Water and Sanitation Cluster, aims - through focus projects, study and the sharing of lessons learnt - to improve access to safe water and effective sanitation for the rising number of urban poor in developing countries. Focus projects are the mainstay of the cluster's work. They yield lessons that inform project fieldwork, help the cluster measure the partnership's efficacy, and identify priority research areas, including technology and terrain, land tenure and non-payment culture. Through focus projects, the cluster seeks to illustrate that - by pooling their unique assets and expertise - tri-sector partnerships can truly provide mutual gains for all. Governments can ensure the health of their citizens with safe water and effective sanitation, while apportioning the financial and technical burden. Corporations can showcase good works while ensuring financial sustainability over the long term, and communities can gain a real voice in their development. Lessons from the Focus Projects The Water and Sanitation Cluster's eight focus projects respond to the specific demands and conditions of the communities they serve. As a result of these dynamics, each project's objective is a work in progress. They include: a drinking water supply and sewer system in the El Pozón quarter, Cartagena, Colombia; water supply improvements to Marunda District, Jakarta, Indonesia; restructuring public water service in shanty towns, Port-au-Prince, Haiti; developing water supply and sanitation services for marginal urban populations, La Paz and El Alto, Bolivia: innovative water solutions for underprivileged districts, Buenos Aires, Argentina; sustainable water and wastewater services in underprivileged areas, Eastern Cape and Northern Province, South Africa; management of water services, Durban and Pietermaritzburg, South Africa; and upgrade and expansion of local water networks, Dakar, Senegal. The secretariat has determined that the best way to learn from the focus projects is through a three-angled line of inquiry. The iterative and complementary approaches are as follows: • Sector-by-sector analysis. The workshop series provides an example whereby each sector was brought together to conduct its own SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) analysis of working in partnership with the other two sectors. The actors from the different sectors approach the partnerships in different ways. They have different expectations, fears, capacities, skills and strengths. As the theory suggests, these combine with their other sector counterparts to enhance the projects. Though initial findings are fairly straightforward to an outside observer versed in these types of relationships, the most critical factor is overcoming the stereotypes of different sector counterparts. It proves critical to make concrete assessments of the contributions that individual sectors make, and to build up their confidence in making these contributions. • Theme-based review. This approach attempts to address the impact of the tri-sector relationships on specific project components or project themes. In 2000, a survey was commissioned of the way the partnerships impact on cost recovery in poor areas. Perhaps as testimony to the infancy of the partnership approach, the analysis at the local level of how the partnerships were impacting on specific themes should be deepened. The cluster continues to encourage the partners and partnerships to clarify their working relationships. It also intends to use their experiences to make recommendations to others embarking on a similar tri-sector approach. Activities for 2001 in this area include research and surveys on partnership and alternative approaches to service provision, partnership and land tenure; partnership and regulatory frameworks; and partnership and education/awareness campaigns. • Local-level analysis. This project-by-project or partnership-by-partnership analysis has resulted in the drafting of internal partnership analysis reports that have attempted to document the successes, impacts, challenges and wider contexts of each individual project. The challenge for the secretariat with this approach is that the partnerships are actually living organisms that change on a daily basis. Structures put in place and definitions of roles, responsibilities and budgets are all influential in (and also significantly different between) the eight focus projects. Equally, external events, changes in staff, findings in the communities and other externalities have an impact on the way the partners work together. | |

| Source: Business Partners for Development, Water and Sanitation Cluster | |

| Box 6.22 The Role of Consultants in Restructuring Water and Sanitation Services | |

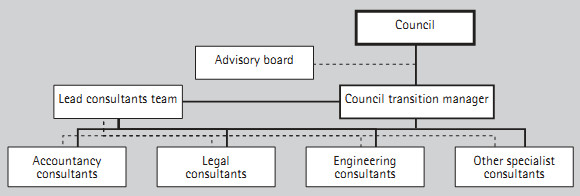

| In common with most emerging economies, water and sanitation services in South Africa are politically sensitive. While the benefits of successful structural change in the water sector are significant and wide ranging, the consequences of failure can be very serious. With such high stakes it is important that client organisations make the best use of the expertise and experience available from specialised consultants with a track record of similar projects. When the Greater Johannesburg Metropolitan Council adopted its IGOLI 2002 plan for restructuring municipal functions (see Boxes 4.4 and 8.5), and determined that a private operator would be procured to manage and operate the new utility, the council recognised the importance of consultants and undertook an international procurement for suitable international experts to act as lead consultants for the water and sanitation restructuring process. The contract was won by a joint venture led by the Halcrow Group of the UK, with VKE Consulting Engineers and Malani Padayachi and Associates of South Africa. HKC Investments (financial analysts) and the Palmer Development Group (operations modelling) joined the lead consultancy team at a later stage. The lead consultants' role included: • preparing the transition programme; • defining the role and terms of reference for other consultants, assistance with procuring and managing consultants; • advising the transition manager on strategic issues; • designing the management contract, and managing the procurement process for the private operator; • preparing the bid data room; • preparing the pre-qualification shortlist and evaluating the bids; • operational and financial modelling, and feasibility analysis; and • preparing the initial strategic business plan. An early task of the lead consultants was to identify the need for additional consultants and to assist in their procurement. In total, 16 separate specialist consultancy firms were engaged during the process, including international legal counsels, local legal advisors, accountants, engineering consultants, communications consultants, human resource consultants and information technology/revenue consultants. In Johannesburg, instead of the typical lump-sum contract for consultancy services, the council appointed the lead consultants on a time-scale basis, with packages of work being contracted-out as the project progressed. This flexible approach worked well for both council and lead consultants, and was almost certainly considerably cheaper than a lump sum would have been.

While the success of the process owed a great deal to the council's leadership and the flexible approach of the transition manager, the structure and approach adopted by the council had a number of clear advantages. The lead consultant's role was that of a true advisor to the transition manager. This person was involved in the detail of the issues, and in the development of ideas, and was responsible for driving the process. This resulted in much greater ownership of the solutions by the council. The lead consultants were engaged with flexible terms of reference that recognised that the scope and extent of services was difficult to define at the start. They were able to respond to events in a flexible and efficient way. In addition, sub-consultants were contracted directly to the council, but the management and coordination of consultants was shared between the transition manager and the lead consultants; and by procuring the sub-consultants individually, the council was able to select the best specialist firms for the tasks. This would not have been possible with a traditional consultancy approach, in which the client organisation must accept the team assembled by the winning consultant. | |

| Chris Ricketson, Halcrow Group, UK, lead consultants to the Greater Johannesburg Metropolitan Council | |