The challenge of integration

105 The degree to which partnerships integrate the processes of two or more organisations varies. Strategic alliances are at the un-integrated end of this spectrum because they involve little if any joint decision making or delivery. Some LSPs have operated in this fashion, although they are increasingly taking on responsibilities for delivery. The creation of a new organisational form, such as a care trust, lies at the fully integrated end of the spectrum because it constitutes a separate legal entity. We can regard a children's trust as a virtual new organisational form, although it is not a separately constituted entity.

106 Corporate governance arrangements cover the risks involved at both ends of the spectrum. They involve different degrees of integration. Some organisations work in partnerships to achieve a common operational objective for a limited time and create specific joint procedures and structures to achieve it; for example, NRF regeneration partnerships, and Supporting People partnerships of local authorities, PCTs and probation services. These partnerships require joint commissioning arrangements for one budget from three or more different statutory partners, but only one takes the role of accountable body.

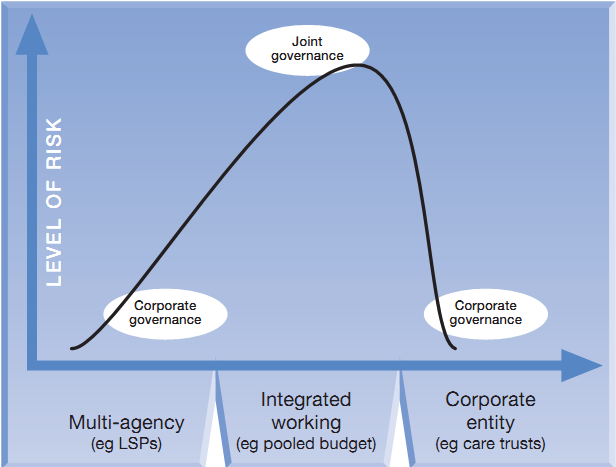

107 A partnership's governance requirements depend on its degree of integration. Corporate governance arrangements are generally unaffected where organisations come together at a strategic level, in loose, multi-agency working arrangements. The boundaries between the organisations are clear; accountability, service planning, complaints and redress remain corporate functions. As the partners' shared activities become progressively more integrated, it becomes harder to clarify internal lines of accountability between them (Figure 7). Clarity on decision making about finance and the commitment of resources is essential.

108 It is particularly important to have internal clarity over line management responsibilities where joint posts are involved. Staff involved in partnership work need to know which organisation has line management responsibility for them; these may be secondees, staff in jointly funded posts, or staff from different organisations who are working in the same office or service outlet, such as health and social care staff, or police officers and neighbourhood wardens on joint patrols.

109 One director of public health noted a trend in cross-sector working to enhance the role of home help to hybrid social care and health teams. Line management of these posts was:

'…undertaken sometimes by us, and sometimes by the NHS. There are a raft of issues around people working together in integrated teams, for example, through different terms and conditions. We still need to resolve a number of issues both nationally and locally around people crossing between organisations and pension arrangements and VAT arrangements. Very practical things.'

Corporate director of health and social care, unitary council

Figure 7 Different levels of integration present different governance risks. |

|

Source: Audit Commission |

110 Normal management processes, such as supervision, reward and discipline, are potentially more difficult when staff are involved in joint-working arrangements. Partners need to ensure that they know how their staff will react when engaged in combined operational activity, such as joint patrols by police and neighbourhood wardens, or when health and social care staff work together on a reception desk. Corporate procedures that set out how to deal with complaints and other incidents may prove less easy to manage if direct line management responsibility is not clear.

111 Integration may throw up difficulties arising from different organisational systems and processes. Integrated service planning or delivery requires greater integration of support and information functions through ICT. Therefore, partners need to develop a joint information strategy that outlines how and when they will bring information systems together across the partners (Case study 8).

Case study 8 West Berkshire Council openly shares knowledge with its partners on the LSP. Information systems and protocols are available to support partnership objectives and clear information sharing protocols are in place, which help to diffuse conflict and promote openness. Most partners attend partnership meetings and joint working takes place with other statutory bodies. For example, the police have seconded staff to the Council to investigate closer methods of working and to forge productive working relationships. Partners feel that the Council has a flexible approach to partnership working, which enables them to respond to changing needs. Source: Audit Commission, 2004 |

112 Joint commissioning highlights the governance difficulties that integration can bring (Box C).

Box C The Supporting People programme illustrates the difficulty of securing effective governance in partnerships. Supporting People commissioning bodies led by the administering local authority (ALA) and involving health, probation and district councils in two-tier authorities should set the local strategy and drive local programmes. Over 63 Audit Commission inspections show that, two years after the launch of the scheme (of £1.72 billion funding), some of those involved in these overarching commissioning bodies are still not clear about their roles and responsibilities. In some cases, health and/or probation partners do not attend regularly and the arrangement whereby one PCT or district council representative can speak for or commit their peers is unclear. In reality in these local authorities, the commissioning body is not governing the programme and where the role of the accountable officer is also weak, by default, leadership falls to the council's middle management Supporting People lead officer. In some cases, there are no reporting arrangements from that individual to the council's treasurer, members and senior managers, because the council does not recognise that it has any responsibility to take on that governance role. There are examples of high-performing ALAs where governance and partnerships are robust and sustainable but these are currently in the minority. In weaker ALAs Supporting People lead officers cannot secure a sustained commitment from senior officers in partner organisations, ensure a strategic approach across all partners, nor can they ensure the joint planning of Supporting People and wider budgets. Responsibility for dealing with the consequences of service failures or closures is not always shared and neither are partner resources pooled to address those consequences. At worst, vulnerable users can lose services altogether with no clarity about who is responsible for the service loss and for any corresponding failure to find a replacement service. Source: Audit Commission (Supporting People, October 2005) |

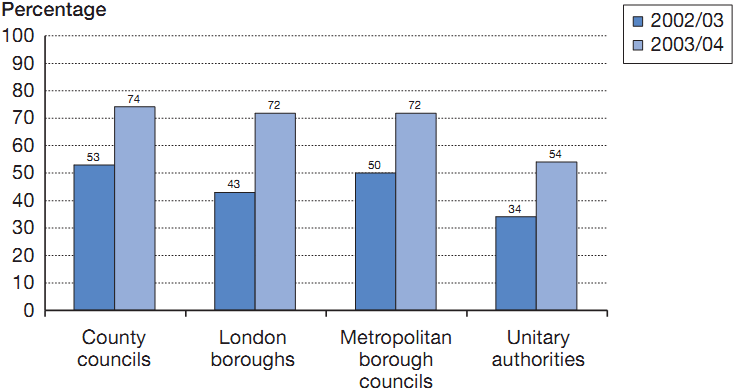

113 Integration has proceeded furthest in pooled budgets arrangements and other flexibilitiesI under Section 31 of the 1999 Health Act (Figures 8 and 9, overleaf).

Figure 8 There has been a marked growth in use of pooled budgets in local government. |

|

Source: Audit Commission, 2004 |

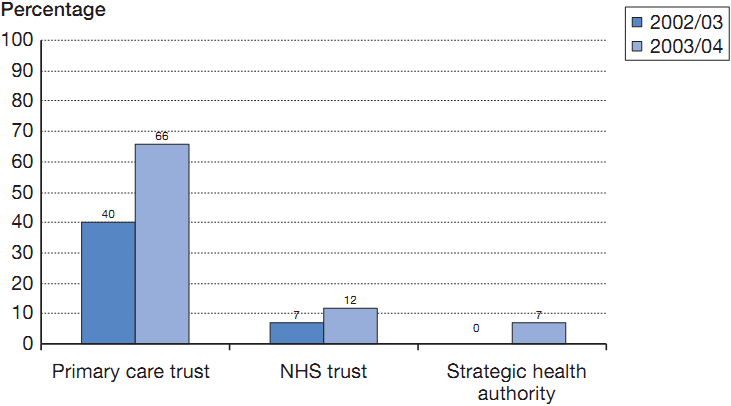

114 In the NHS, the use of pooled budgets shows a similar increase in 2003/04 over 2002/03, although from a lower base than in local government (Figure 9).

115 Pooled budgets are the clearest example of integration between separate organisations and most clearly illustrate the balance between risks and benefits in partnerships. They have the potential to bring significant benefits, in terms of greater clarity of purpose, increased resources and better services. They also, however, bring the risks that this section of the report has identified. These risks require careful management to realise the anticipated benefits and this is achieved through the pool memorandum of accounts. The host to the pooled budget arrangement prepares the pool memorandum of accounts, which shows the pattern of the budget's income and expenditure, and sends it to each of the partners for inclusion in their own statements of accounts. The role of host, which can be adopted by any best value authority, does not confer any additional risks to an organisation; participating organisations share these risks. Agreeing the pooled budget memorandum is important precisely because accountability remains with organisations that are not in charge of the day-to-day management of the budget.

Figure 9 There has been a marked growth in use of pooled budgets in the NHS, albeit from a lower base than in local government. |

|

Source: Audit Commission, 2004 |

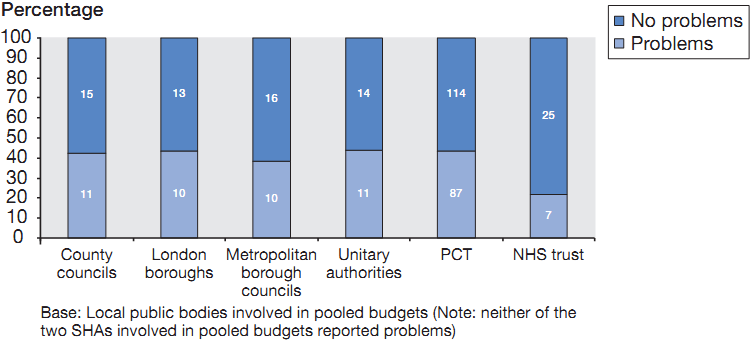

116 Governance needs to be robust, but auditors report problems with reaching agreement on the memorandum in a substantial proportion of local authorities and NHS bodies.

Figure 10 Substantial proportions of local public bodies involved in pooled budgets reported problems in 2003/04. |

|

Source: Audit Commission, 2003/04 |

___________________________________________________________________________

I Along with pooled budgets, partners can enter agreements that specify a lead commissioning role for one partner, or join commissioning roles between them.