Complaints and redress

127 The ability to manage complaints effectively is the acid test of public accountability in partnership working. Therefore, it is central to the governance of partnerships.

128 The assertion that the public does not care which organisation provides the service may be true for many service users. But when things go wrong, the public plays close attention to which organisations and which people within them it can hold accountable. A recent National Audit Office report (Ref. 18) makes clear that this is an underdeveloped area for corporate bodies:

'…public sector redress systems have developed piecemeal over many years and in the past they have rarely been systematically thought about as a whole.'

129 Few partnerships have established joint complaints procedures or determined precisely which organisation is responsible for redress if things go wrong. This is a feature of the poor risk management in partnerships, which stems from a lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities in decision making. Fundamental issues between partners about public accountability also influence whether partnerships have effective complaints procedures. Some partnerships are working to raise public awareness of shared accountability and are stressing joint ownership of problems. However, local authority partners may feel that elected representatives have better direct links with the public; they may be unwilling to shoulder shared accountability because of the particular legitimacy that elected representation brings.

'There's an overriding issue I think for local government, because the people who are ultimately held responsible are elected members, being democratically elected. I think that's got a different set of demands to it compared with police, health or others, because they've got a different set of expectations and relationship with the public. Ours is very, very direct.'

Local authority chief executive

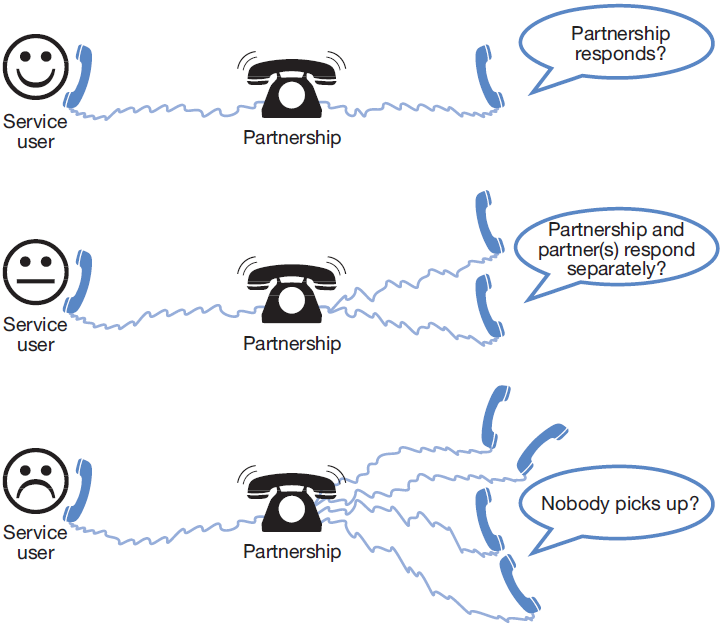

130 The Local Government Ombudsman reports a gradual increase in the number of complaints about partnerships. He has raised concerns about who is responsible for the decisions in these partnerships (Figure 12). There are two issues: the difficulty in establishing the respective responsibilities of the partners, and complaints that affect the jurisdiction of more than one Ombudsman.

'We have a very real example of that at the moment around placements for children or adults with disabilities. We have a panel and we look at the child's needs and we do that in a very joined up, grown up way. If the panel decides not to fund a place and the parents complain to us, we tell them that they can go through our complaint system about our bit, but that this is a multi-agency decision. That case has actually gone to the ombudsman but they don't have a remit over health. So it's a very practical issue.'

Corporate director of health and social care, unitary council

131 If partnerships fail to document their processes then the public will not know which agency to contact, or which individuals within it deal with complaints.

…the way the system seems to work now it relies on people having the time and the patience to want to find out who the agency is and who they should report something to by going through a phone book or a website, but for most people life is too short.

Assistant director of resources and social services, county council

Figure 12 The public is not well served. |

|

132 Like corporate bodies, partnerships need to recognise the feedback value of complaints. This is critical information that should influence decisions about service delivery. Complaints also present an opportunity to engage with the wider public. Partnerships need to take a collective approach to developing an effective complaints procedure; this means that they can deal with complaints collaboratively, or quickly and efficiently channel the complainant to the appropriate partner's corporate system.